Over on Crime De-Coder, I have up a pre-release of my book, Data Science for Crime Analysis with Python.

I have gotten asked by so many people “where to learn python” over the past year I decided to write a book. Go check out my preface on why I am not happy with current resources in the market, especially for beginners.

I have the preface + first two chapters posted. If you want to sign up for early releases, send me an email and will let you know how to get an early copy of the first half of the book (and send updates as they are finished).

Also I have up the third installment of the AltAc newsletter. Notes about the different types of healthcare jobs, and StatQuest youtube videos are a great resource. Email me if you want to sign up for the newsletter.

So the other day I showed how to fit a beta-binomial model in python. Today, in a quick post, I am going to show how to estimate standard errors for such fitted models.

So in scipy, you have distribution.fit(data) to fit the distribution and return the estimates, but it does not have standard errors around those estimates. I recently had need for gamma fits to data, in R I would do something like:

# this is R code

library(fitdistrplus)

x <- c(24,13,11,11,11,13,9,10,8,9,6)

gamma_fit <- fitdist(x,"gamma")

summary(gamma_fit)And this pipes out:

> Fitting of the distribution ' gamma ' by maximum likelihood

> Parameters :

> estimate Std. Error

> shape 8.4364984 3.5284240

> rate 0.7423908 0.3199124

> Loglikelihood: -30.16567 AIC: 64.33134 BIC: 65.12713

> Correlation matrix:

> shape rate

> shape 1.0000000 0.9705518

> rate 0.9705518 1.0000000Now, for some equivalent in python.

# python code

from scipy.optimize import minimize

from scipy.stats import gamma

x = [24,13,11,11,11,13,9,10,8,9,6]

res = gamma.fit(x,floc=0)

print(res)And this gives (8.437256958682587, 0, 1.3468401423927603). Note that python uses the scale version, so 1/scale = rate, e.g. 1/res[-1] results in 0.7424786123640676, which agrees pretty closely with R.

Now unfortunately, there is no simple way to get the standard errors in this framework. You can however minimize the parameters yourself and get the things you need – here the Hessian – to calculate the standard errors yourself.

Here to make it easier apples to apples with R, I estimate the rate parameter version.

# minimize negative log likelihood

def gll(parms,data):

alpha, rate = parms

ll = gamma.logpdf(data,alpha,loc=0,scale=1/rate)

return -ll.sum()

result = minimize(gll,[8.,0.7],args=(x),method='BFGS')

se = np.sqrt(np.diag(result.hess_inv))

# printing results

np.stack([result.x,se],axis=1)And this gives:

array([[8.43729465, 3.32538824],

[0.74248193, 0.30255433]])Pretty close, but not an exact match, to R. Here the standard errors are too low (maybe there is a sample correction factor?).

Some quick tests with this, using this scale version tends to be a bit more robust in fitting than the rate version.

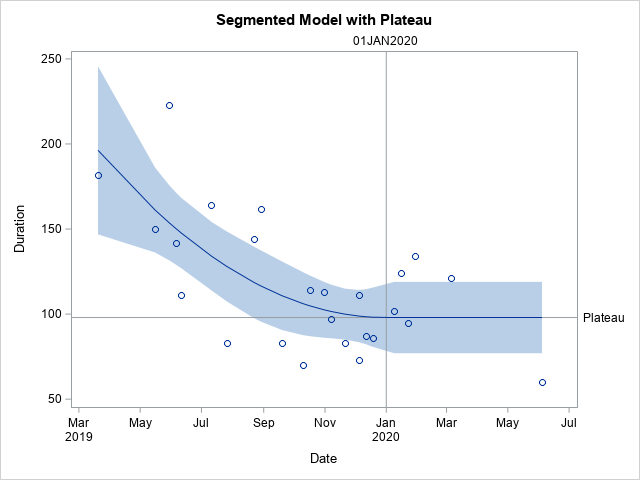

The context of this, a gamma distribution with a shape parameter greater than 1 has a hump, and less than 1 is monotonically decreasing. This corresponds to the “buffer” hypothesis in criminology for journey to crime distributions. So hopefully some work related to that coming up soonish!

And doing alittle more digging, you can get “closed form” estimates of the parameters based on the Fisher Information matrix (via Wikipedia).

# Calculating closed form standard

# errors for gamma via Fisher Info

from scipy.special import polygamma

from numpy.linalg import inv

import numpy as np

def trigamma(x):

return float(polygamma(1,x))

# These are the R estimates

shape = 8.4364984

rate = 0.7423908

n = 11 # 11 observations

fi = np.array([[trigamma(shape), -1/rate],

[-1/rate, shape/rate**2]])

inv_fi = inv(n*fi) # this is variance/covariance

np.sqrt(np.diagonal(inv_fi))

# R reports 3.5284240 0.3199124

# python reports 3.5284936 0.3199193

I do scare quotes around closed form, as it relies on the trigamma function, which itself needs to be calculated numerically I believe.

If you want to go through the annoying math (instead of using the inverse above), you can get a direct one liner for either.

# Closed for for standard error of shape np.sqrt(shape / (n*(trigamma(shape)*shape - 1))) # 3.528493591892887 # This works for the scale or the rate parameterization np.sqrt((trigamma(shape))/ (n*rate**-2*(trigamma(shape)*shape - 1))) # 0.31995664847081356 # This is the standard error for the scale version scale = 1/rate np.sqrt((trigamma(shape))/ (n*scale**-2*(trigamma(shape)*shape - 1))) # 0.5803962127677769