The other day I had the task of comparing two distributions of a continous variable between two groups. One complication that arose when trying to make graphical comparisons was that the groups had unequal sample sizes. I’m making this blog post mainly because many of the options I will show can’t be done in SPSS directly through the graphical user interface (GUI), but understanding alittle bit about how the graphic options work in the GPL will help you make the charts you want to make without having to rely solely on what is available through the GUI.

The basic means I typically start out at are histograms, box-plots and a few summary statistics. The beginning code is just how I generated some fake data to demonstrate these graphics.

SET TNumbers=Labels ONumbers=Labels OVars=Labels TVars=Labels.

dataset close ALL.

output close ALL.

*making fake cases data.

set seed = 10.

input program.

loop #i = 1 to 5000.

if #i <= 1500 group = 1.

if #i > 1500 group = 2.

end case.

end loop.

end file.

end input program.

dataset name sim.

execute.

*making approximate log normal data.

if group = 1 time_event = (RV.LNORMAL(0.5,0.6))*10.

if group = 2 time_event = (RV.LNORMAL(0.6,0.5))*10.

variable labels time_event 'Time to Event'.

value labels group

1 'Group 1'

2 'Group 2'.

formats group time_event (F3.0).

variable level group (nominal).

*Good First Stabs are Histograms and Box plots and summary statistics.

GRAPH

/HISTOGRAM=time_event

/PANEL ROWVAR=group ROWOP=CROSS.

EXAMINE VARIABLES=time_event BY group

/PLOT=BOXPLOT

/STATISTICS=NONE

/NOTOTAL.

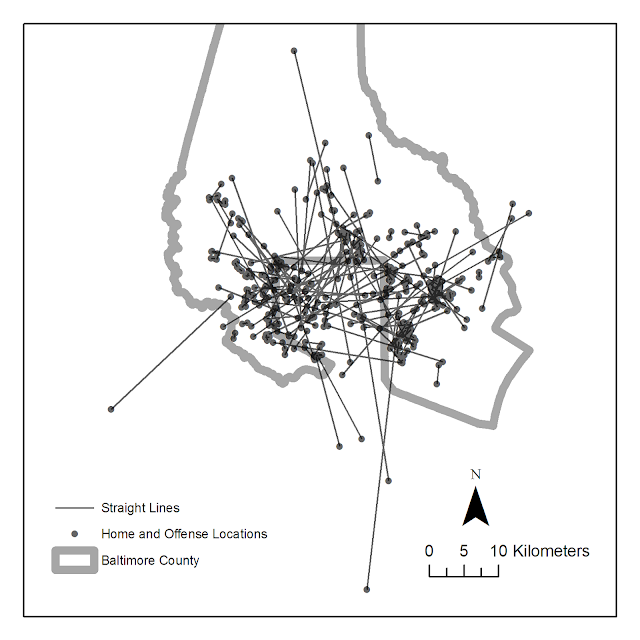

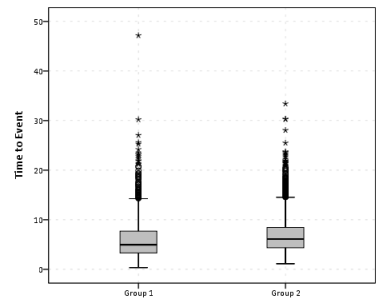

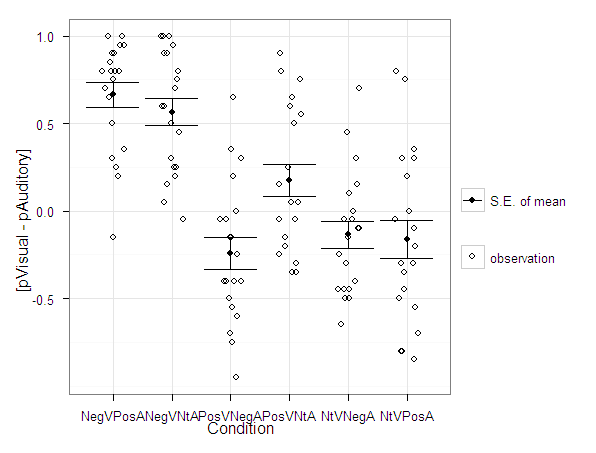

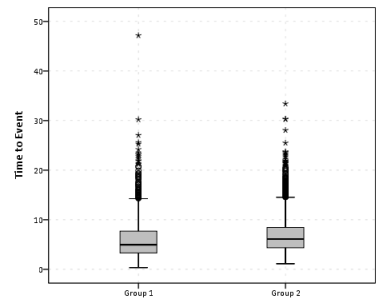

So this essentially produces a summary statistics table, a paneled histogram, and a box-plot (shown below).

First blush this is an alright way to visually assess various characteristics of each distribution, and the unequal sizes of each group is not problematic when comparing the summary statistics nor the box-plots. The histogram produced by SPSS though is the frequency of events per bin, and this makes it difficult to compare Group 2 to Group 1, as Group 2 has so many more observations. One way to normalize the distributions is to make a histogram showing the percent of the distribution that falls within that bin as oppossed to the frequency. You can actually do this through the GUI through the Chart Builder, but it is buried within some various other options, below is a screen shot showing how to change the histogram from frequency to percents. Also to note, you need to change what the base percentage is built off of, by clicking the Set Parameters button (circled in red) and then toggling the denominator choice in the new pop up window to total for each panel (if you click on the screen shot images they will open up larger images).

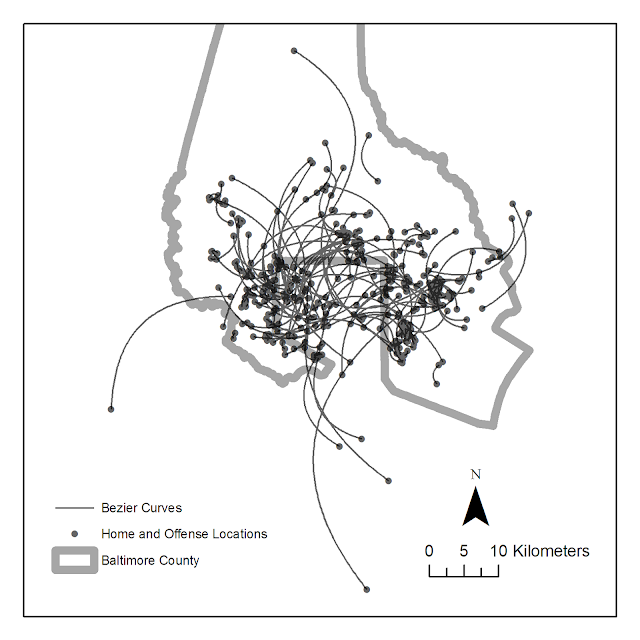

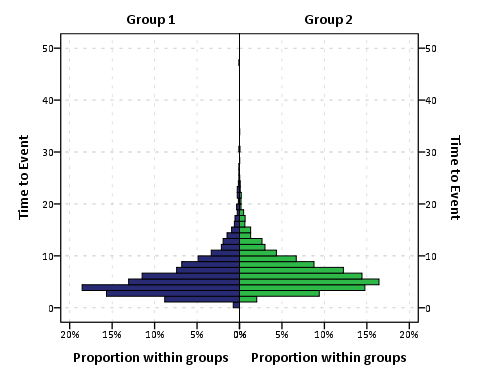

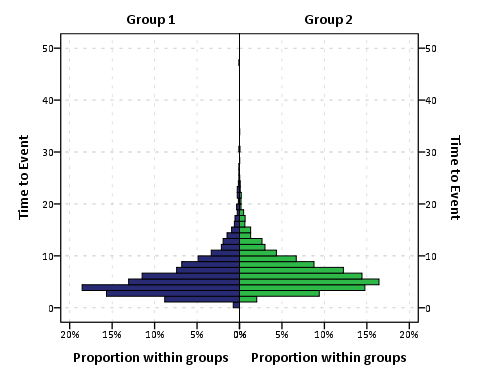

Sometimes you can’t always get to what you want through the chart builder GUI though. For an example, I originally wanted to make a population pyramid type chart, and it does not allow you to specify the base percent like that through the GUI. So I originally made a pyramid chart like this;

And here is what the pasted output appears like.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event group MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: time_event=col(source(s), name("time_event"))

DATA: group=col(source(s), name("group"), unit.category())

COORD: transpose(mirror(rect(dim(1,2))))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), opposite(), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Frequency"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(3), label("group"), opposite(), gap(0px))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color), null())

SCALE: cat(dim(3), include("1", "2"))

ELEMENT: interval(position(summary.count(bin.rect(time_event*1*group))), color.interior(group))

END GPL.

To get the percent bins instead of the count bins takes one very simple change to summary specification on the ELEMENT statement. One would simply insert summary.percent.count instead of summary.count. Which will approximately produce the chart below.

You can actually post-hoc edit the traditional histogram to make a population pyramid (by mirroring the panels), but by examining the GPL produced for the above chart gives you a glimpse of the potential possibilities you can do to produce a variety of charts in SPSS.

Another frequent way to assess continuous distributions like those displayed so far is by estimating kernel density smoothers through the distribution (sometime referred by the acronym kde (e is for estimate). Sometimes this is perferable because our perception of the distribution can be too highly impacted by the histogram bins. Kernel density smoothers aren’t available through the GUI at all though (as far as I’m aware), and so you would have only known the potential exisited if you looked at the examples in the GPL reference guide that comes with the software. Below is an example (including code).

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event group MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: time_event=col(source(s), name("time_event"))

DATA: group=col(source(s), name("group"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Kernel Density Estimate"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior))

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), include("1", "2"))

ELEMENT: line(position(density.kernel.epanechnikov(time_event*group)), color(group))

END GPL.

Although the smoothing is useful, again we have a problem with the unequal number of cases in the distributions. To solve this, I weighted cases inversely proportional to the number of observations that were in each group (i.e. the weight for group 1 is 1/1500, and the weight for group 2 is 1/3500 in this example). This should make the area underneath the lines sum to 1, and so to get the estimate back on the original frequency scale you would simply multiply the marginal density estimate by the total in the corresponding group. So for instance, the marginal density for group 2 at the time to event value of 10 is 0.05, so the estimated frequency given 3500 cases is .05 * 3500 = 175. To get back on a percentage scale you would just multiply by 100.

AGGREGATE

/OUTFILE=* MODE=ADDVARIABLES

/BREAK=group

/cases=N.

compute myweight = 1/cases.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event group myweight MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"), weight(weightedVar))

DATA: weightedVar=col(source(s), name("myweight"))

DATA: time_event=col(source(s), name("time_event"))

DATA: group=col(source(s), name("group"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Weighted Kernel Density Estimate"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior))

GUIDE: text.footnote(label("Density is weighted inverse to the proportion of cases within each group. The number of cases in group 1 equals 1,500, and the number of cases ingroup 2 equals 3,500."))

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), include("1", "2"))

SCALE: linear(dim(2))

ELEMENT: line(position(density.kernel.epanechnikov(time_event*group)), color(group))

END GPL.

One of the critiques of this though is that choosing a kernel and bandwidth is ad-hoc (I just used all of the default kernal and bandwidth in SPSS here, and it differed in unexpected ways between the frequency counts and the weighted estimates which is undesirable). Also you can see that some of the density is smoothed over illogical values in this example (values below 0). Other potential plots are the cumualitive distribution and QQ-plots comparing the quantiles of each distribution to each other. Again these are difficult to impossible to obtain through the GUI. Here is the closest I could come to getting a cumulative distribution by groups through the GUI.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event COUNT()[name="COUNT"] group

MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: time_event=col(source(s), name("time_event"))

DATA: COUNT=col(source(s), name("COUNT"))

DATA: group=col(source(s), name("group"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Cumulative Percent of Total"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior))

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), include("1", "2"))

ELEMENT: line(position(summary.percent.cumulative(time_event*COUNT, base.all(acrossPanels()))),

color.interior(group), missing.wings())

END GPL.

This is kind of helpful, but not really what I want. I wasn’t quite sure how to change the summary statistic functions in the ELEMENT statement to calculate percent within groups (I assume it is possible, but I just don’t know how), so I ended up just making the actual data to include in the plot. Example syntax and plot below.

sort cases by group time_event.

compute id = $casenum.

AGGREGATE

/OUTFILE=* MODE=ADDVARIABLES

/BREAK=group

/id_min=MIN(id)

/id_max=MAX(id).

compute cum_prop = ((id +1) - id_min)/(id_max - (id_min - 1)).

*Here is the cumulative proportion I want.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event cum_prop group MISSING=LISTWISE

REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: time_event=col(source(s), name("time_event"))

DATA: cum_prop=col(source(s), name("cum_prop"))

DATA: group=col(source(s), name("group"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Time to Event"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Cumulative Percent within Groups"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior))

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), include("1", "2"))

ELEMENT: line(position(time_event*cum_prop), color.interior(group), missing.wings())

END GPL.

These cumulative plots aren’t as problematic with bins as are the histograms or kde estimates, and in fact many interesting questions are much easier addressed with the cumulative plots. For instance if I wanted to know the proportion of events that happen within 10 days (or its complement, the proportion of events that do not yet occur within 10 days) this is an easy task with the cumulative plots. This would be at best extremely difficult to determine with the histogram or density estimates. The cumulative plot also gives a graphical comparisons of the distribution (although perhaps not as intuitive as the histogram or kde estimates). For instance it is easy to see the location of group 2 is slightly shifted to the right.

The last plot I present is a QQ-plot. These are typically presented as plotting an empirical distribution against a theoretical distribution, but you can plot two empirical distributions against each other. Again you can’t quite get the QQ-plot of interest though the regular GUI, and you have to do some data manipulation to be able to construct the elements of the graph. You can do QQ-plots against a theoretical distribution in the PPLOT command, so you could make seperate QQ plots for each subgroup, but this is less than ideal. Below I paste an example of my constructed QQ-plot, along with syntax showing how to use the PPLOT command for seperate sub-groups (using SPLIT FILE) and getting the quantiles of intrest using the RANK command.

sort cases by group time_event.

split file by group.

PPLOT

/VARIABLES=time_event

/NOLOG

/NOSTANDARDIZE

/TYPE=Q-Q

/FRACTION=BLOM

/TIES=MEAN

/DIST=LNORMAL.

split file off.

*Not really what I want - I want Q-Q plot of one group versus the other group.

RANK VARIABLES=time_event (A) BY group

/NTILES(99)

/PRINT=NO

/TIES=MEAN.

*Now aggregating to new dataset.

DATASET DECLARE quantiles.

AGGREGATE

/OUTFILE='quantiles'

/BREAK=group Ntime_ev

/time_event=MAX(time_event).

dataset activate quantiles.

sort cases by Ntime_ev group.

casestovars

/id = Ntime_ev

/index = group.

DATASET ACTIVATE quantiles.

* Chart Builder.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=time_event.1[name="time_event_1"]

time_event.2[name="time_event_2"] MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: time_event_1=col(source(s), name("time_event_1"))

DATA: time_event_2=col(source(s), name("time_event_2"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Quantiles Time to Event Group 1"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Quantiles Time to Event Group 2"))

ELEMENT: point(position(time_event_1*time_event_2))

ELEMENT: line(position(time_event_1*time_event_1))

END GPL.

Although I started out with a simple question, it takes a fair bit of knowledge about both graphically comparing distributions and data management (i.e. how to shape your data) to be able to make all of these types of charts in SPSS. I intentionally made the reference distributions very similar, and if you just stuck with the typical histogram the slight differences in location and scale between the two distributions would not be as evident as it is with the kernel density, the cumulative distribution or the QQ-plots.