The title is probably not that clear, but I’ve seen this request a few times and have used this trick in one my projects, so figured it would be a worthwhile topic to illustrate. So the problem is you have a background distribution, and you want to tailor a set of individual charts showing the unique individuals score against the background distribution. See two examples (1,2) of this question. In the first link I showed how one can do this by artificially duplicating the data in a specific way using VARSTOCASES and then using SPLIT FILE to generate the separate charts. Here I will show a python based solution that does not require duplicating the data.

So first we will start off with a set of fake student scores, 20 students with 5 scores each.

*Create some fake data, student test scores.

SET SEED 10.

INPUT PROGRAM.

STRING Student (A1).

LOOP #i = 1 TO 5.

LOOP #j = 1 TO 20.

COMPUTE Student = STRING(#j+64,PIB).

COMPUTE Score = RND(RV.NORMAL(100,10)).

END CASE.

END LOOP.

END LOOP.

END FILE.

END INPUT PROGRAM.

DATASET NAME Student_Scores.

FORMATS Score (F3.0).

EXECUTE.Now the students are listed as strings, but here I am going to use AUTORECODE to automatically turn the strings into number variables, and more importantly for what follows create a set of value labels corresponding to those unique strings.

*Use Auto-recode to make the variables 1 to N.

AUTORECODE VARIABLES = Student /INTO Student_N.

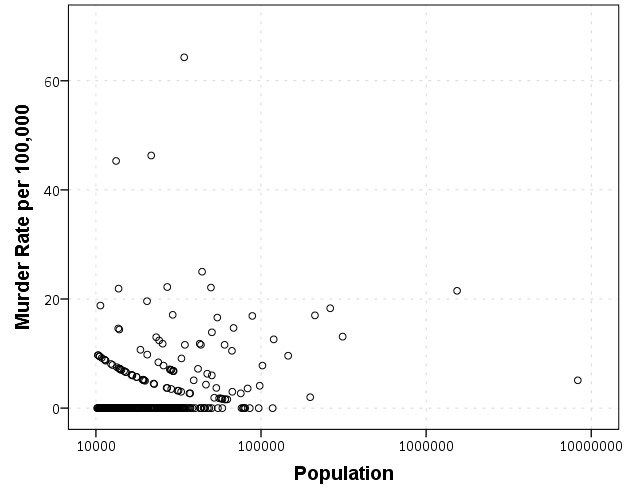

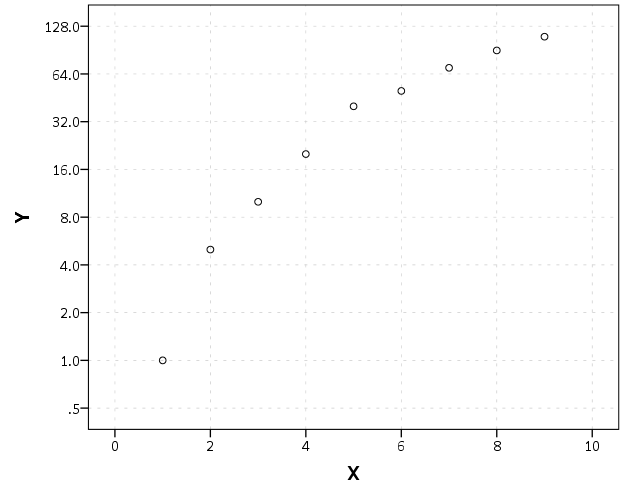

FORMATS Student_N (F6.0).Now the workflow I want to do is to make a set of charts with the background a boxplot for the whole class, and then the individual students scores as foreground dots. To do this I will make a second set of scores that are missing for everyone except that one particular student, the specify MISSING=VARIABLEWISE on the GGRAPH command, and then superimpose Score2 over the boxplot of Score.

*Example of Individual chart.

NUMERIC flag (F1.0) Score2 (F3.0).

DO IF Student_N = 1.

COMPUTE Score2 = Score.

COMPUTE flag = 1.

ELSE.

COMPUTE Score2 = $SYSMIS.

COMPUTE flag = 0.

END IF.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=Score Score2 flag MISSING = VARIABLEWISE

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: Score=col(source(s), name("Score"))

DATA: Score2=col(source(s), name("Score2"))

COORD: rect(dim(1), transpose())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Score"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.visible), null())

GUIDE: text.title(label("Student: A"))

ELEMENT: schema(position(bin.quantile.letter(Score)), color.interior(color.grey))

ELEMENT: point.dodge.symmetric(position(bin.dot(Score2)), color.interior(color.red))

END GPL.

*cleaing up temp variables.

MATCH FILES FILE = * /DROP flag Score2.

There are other ways to do this, like using the visible option in GPL aesthetics, but I don’t do that here because they still exist in the chart but simply aren’t shown. This causes problems with the dodging, and if you sent the chart in vector format the information would still be contained in the chart (e.g. if you need to aggregate the background data to be obfuscated for confidentiality reasons you don’t want it in the chart even if it is invisible). Here even the outlier dots in the boxplot are potentially disseminating confidential information, but for simplicity I don’t worry about that here (my syntax at the developerworks forum showed how you can build your own boxplot without having the points, it would be nice to have a no points option for the schema element).

So now the problem is looping through all of the individual students and generating a chart for each one. That is where the AUTORECODE comes in handy. I can grab all of the value labels from the SPSS dictionary and place them in a Python dictionary.

*Python to grab the different students.

BEGIN PROGRAM Python.

import spss

spss.StartDataStep()

datasetObj = spss.Dataset()

StudentLab = datasetObj.varlist['Student_N'].valueLabels

print StudentLab #this is a dictionary of all the unique students

spss.EndDataStep()

END PROGRAM.Now with the StudentLab Python dictionary I can loop over the dictionary and submit the SPSS syntax for each unique student (using spss.Submit) using string substitutions. I first create the variables and set there formats outside of the loop (the chart inherits the formats). Then I just set several aesthetics of the charts so they are the same for every chart, e.g. the scale goes between 60 and 150, and the size of the superimposed points is 12.

*Now loop through the students.

OUTPUT CLOSE ALL.

BEGIN PROGRAM Python.

spss.Submit("NUMERIC flag (F1.0) Score2 (F3.0).")

for val, lab in StudentLab.data.iteritems():

spss.Submit("""*Individual score chart.

DO IF Student_N = %d.

COMPUTE Score2 = Score.

COMPUTE flag = 1.

ELSE.

COMPUTE Score2 = $SYSMIS.

COMPUTE flag = 0.

END IF.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=Score Score2 flag MISSING = VARIABLEWISE

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: Score=col(source(s), name("Score"))

DATA: Score2=col(source(s), name("Score2"))

DATA: id=col(source(s), name("$CASENUM"), unit.category())

DATA: flag=col(source(s), name("flag"), unit.category())

COORD: rect(dim(1), transpose())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Score"), delta(10), start(60))

GUIDE: text.title(label("Student: %s"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.visible), null())

SCALE: linear(dim(1), min(60), max(150))

ELEMENT: schema(position(bin.quantile.letter(Score)), color.interior(color.grey))

ELEMENT: point.dodge.symmetric(position(bin.dot(Score2)), color.interior(color.red),

size(size."12"))

END GPL.

""" %(val,lab))

END PROGRAM.I wanted to export these charts in the loop with the students names, using something like:

SpssOutputDoc.SelectLastOutput() #grab last output

SpssOutputDoc.ExportCharts(SpssClient.SpssExportSubset.SpssSelected, path + lab, SpssClient.ChartExportFormat.png)but what happens with this is that it is always one behind (e.g. the first chart is selected in the second loop iteration). So what I did was to stuff all of the charts within a list and then loop over that list, select the chart, and then export it using SpssOutputDoc.ExportCharts (another option would be to use EXPORT OUTPUT and then either delete the output in-between charts or clear it, I wish OMS could export only charts). This would be more annoying with multiple individual charts, and could likely be made more concise, but here it is.

*Now exporting the individual charts.

BEGIN PROGRAM Python.

import SpssClient

SpssClient.StartClient()

SpssOutputDoc = SpssClient.GetDesignatedOutputDoc()

#creating a list of all the charts

OutputItems = SpssOutputDoc.GetOutputItems()

Charts = []

for index in range(OutputItems.Size()):

OutputItem = OutputItems.GetItemAt(index)

if OutputItem.GetType() == SpssClient.OutputItemType.CHART:

Charts.append(OutputItem)

labList = []

for val, lab in StudentLab.data.iteritems():

labList.append(lab)

path = "C:/Users/andrew.wheeler/Dropbox/Documents/BLOG/RepeatingCharts/"

for chart,lab in zip(Charts,labList):

SpssOutputDoc.ClearSelection() #clear prior selections

chart.SetSelected(True) #select chart

#export chart

SpssOutputDoc.ExportCharts(SpssClient.SpssExportSubset.SpssSelected, path + lab, SpssClient.ChartExportFormat.png)

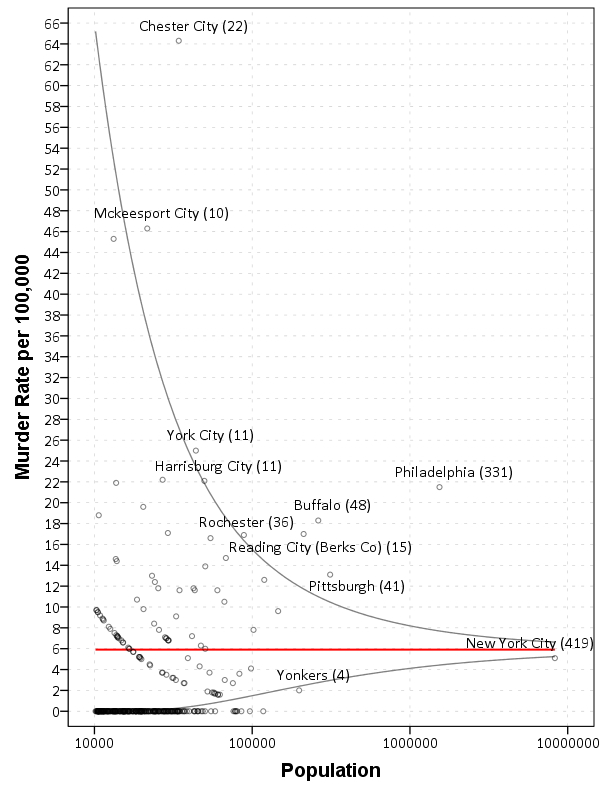

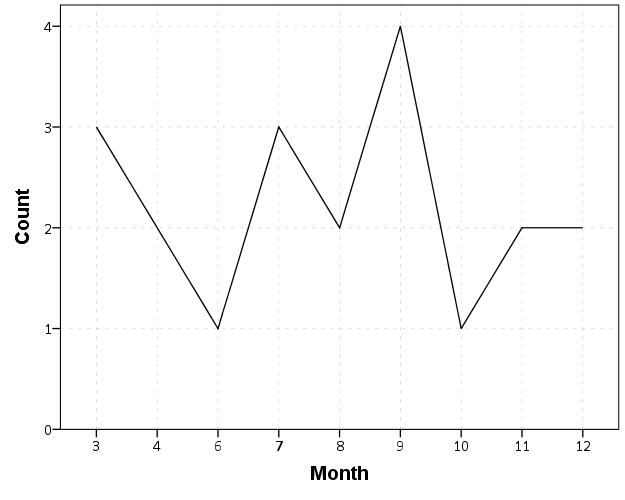

END PROGRAM.Here is a screen shot of the resulting images in my folder.

So this will export the charts to PNG format with the image name the same as the students in the file (so the name needs to be in a format appropriate to save a file name). Annoyingly SPSS appends 1 to the end of all charts, even if it is only exporting one chart. Here is an example of the student G’s chart.

Eventually I will figure out how to send emails via Python, and this would be a good tool for individualized report cards for a class. Here is a copy of the full syntax to more easily run on your local machine (just replace path with a location on your local machine).