It seems like I have come across alot of posts recently about visualizing univariate distributions. Besides my own recent blog post about comparing distributions of unequal size in SPSS, here are a few other blog posts I have recently come across;

- Nathan Yau has a recent post on his flowing data blog, How to Visualize and Compare Distributions.

- Lucas Fenu on his blog gRaphics! has a post, Plotting data and distribution simultaneously (with ggplot2).

- Not a blog post, but Hadley Wickham & Lisa Stryjewski have a working paper that will be of interest, 40 years of box plots.

Such a variety of references is not surprising though. Examining univariate distributions is a regular task for data analysis and can tell you alot about the nature of data (including potential errors in the data). Here are some posts on the Cross Validated Q/A site of related interest I have compiled;

- Wondering what this bean plot analysis chart means

- What are good data visualization techniques to compare distributions?

- How to improve standard visualizations of a univariate distribution?

- Analyze and visualize participants response towards particular condition

- How to scale violin plots for comparisons?

In particular the recent post on bean plots and Luca Fenu’s post motivated my playing around with SPSS to produce the bean plots here. Note Jon Peck has published a graphboard template to generate violin plots for SPSS, but here I will show how to generate them in the usual GGRAPH commands. It is actually pretty easy, and here I extend the violin plots to include the beans suggested in bean plots!

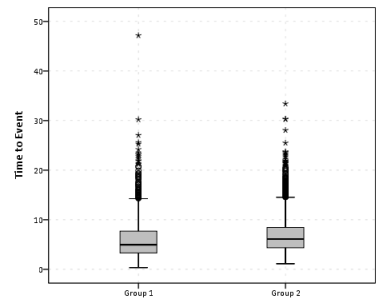

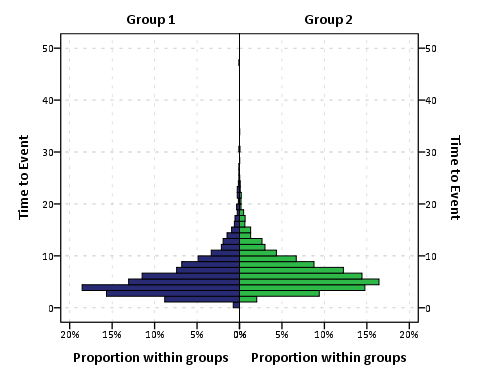

A brief bit about the motivation for bean plots. Besides consulting the article by Peter Kampstra, one is interested in viewing a univariate continuous distribution among a set of different categories. To do this one uses a smoothed kernel density estimate of the distribution for each of the subgroups. When viewing the smoothed distribution though one loses the ability to identify patterns in the individual data points. Patterns can mean many things, such as outliers, or patterns such as striation within the main body of observations. The bean plot article gives an example where striation in measurements at specific inches can be seen. Another example might be examining the time of reported crime incidents (they will have bunches at the beginning of the hour, as well as 15, 30, & 45 minute marks).

Below I will go through a brief series of examples demonstrating how to make bean plots in SPSS.

SPSS code to make bean plots

First I will make some fake data for us to work with.

******************************************.

set seed = 10.

input program.

loop #i = 1 to 1000.

compute V1 = RV.NORM(0,1).

compute groups = TRUNC(RV.UNIFORM(0,5)).

end case.

end loop.

end file.

end input program.

dataset name sim.

execute.

value labels groups

0 'cat 0'

1 'cat 1'

2 'cat 2'

3 'cat 3'

4 'cat 4'.

******************************************.Next, I will show some code to make the two plots below. These are typical kernel density estimates of the V1 variable I made for the entire distribution, and these are to show the elements of the base bean plots. Note the use of the TRANS statement in the GPL to make a constant value to plot the rug of the distribution. Also note although such rugs are typically shown as bars, you could pretty much always use point markers as well in any situation where you use bars. Below the image is the GGRAPH code used to produce them.

******************************************.

*Regular density estimate with rug plot.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=V1 MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: V1=col(source(s), name("V1"))

TRANS: rug = eval(-26)

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("V1"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Density"))

SCALE: linear(dim(2), min(-30))

ELEMENT: interval(position(V1*rug), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.8"))

ELEMENT: line(position(density.kernel.epanechnikov(V1*1)))

END GPL.

*Density estimate with points instead of bars for rug.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=V1 MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: V1=col(source(s), name("V1"))

TRANS: rug = eval(-15)

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("V1"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Density"))

SCALE: linear(dim(2), min(-30))

ELEMENT: point(position(V1*rug), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.8"))

ELEMENT: line(position(density.kernel.epanechnikov(V1*1)))

END GPL.

******************************************.Now bean plots are just the above plots rotatated 90 degrees, adding a reflection of the distribution (so the area of the density is represented in two dimensions), and then further paneled by another categorical variable. To do the reflection, one has to create a fake variable equal to the first variable used for the density estimate. But after that, it is just knowing alittle GGRAPH magic to make the plots.

******************************************.

compute V2 = V1.

varstocases

/make V from V1 V2

/index panel_dum.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=V panel_dum groups MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

COORD: transpose(mirror(rect(dim(1,2))))

DATA: V=col(source(s), name("V"))

DATA: panel_dum=col(source(s), name("panel_dum"), unit.category())

DATA: groups=col(source(s), name("groups"), unit.category())

TRANS: zero = eval(10)

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("V1"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), null())

GUIDE: axis(dim(3), null())

SCALE: linear(dim(2), min(0))

ELEMENT: area(position(density.kernel.epanechnikov(V*1*panel_dum*1*groups)), transparency.exterior(transparency."1.0"), transparency.interior(transparency."0.4"),

color.interior(color.grey), color.exterior(color.grey)))

ELEMENT: interval(position(V*zero*panel_dum*1*groups), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.8"))

END GPL.

******************************************.Note I did not label the density estimate anymore. I could have, but I would have had to essentially divide the density estimate by two, since I am showing it twice (which is possible, and if you wanted to show it you would omit the GUIDE: axis(dim(2), null()) command). But even without the axis they are still reasonable for relative comparisons. Also note the COORD statement for how I get the panels to mirror each other (the transpose statement just switches the X and Y axis in the charts).

I just post hoc edited the chart to get it to look nice (in particular settign the spacing between the panel_dum panel to zero and making the panel outlines transparent), but most of those things can likley be more steamlined by making an appropriate chart template. Two things I do not like, which I may need to edit the chart template to be able to accomplish anyway; 1) There is an artifact of a white line running down the density estimates, (it is hard to see with the rug, but closer inspection will show it), 2) I would prefer to have a box around all of the estimates and categories, but to prevent a streak running down the middle of the density estimates one needs to draw the panel boxes without borders. To see if I can accomplish these things will take further investigation.

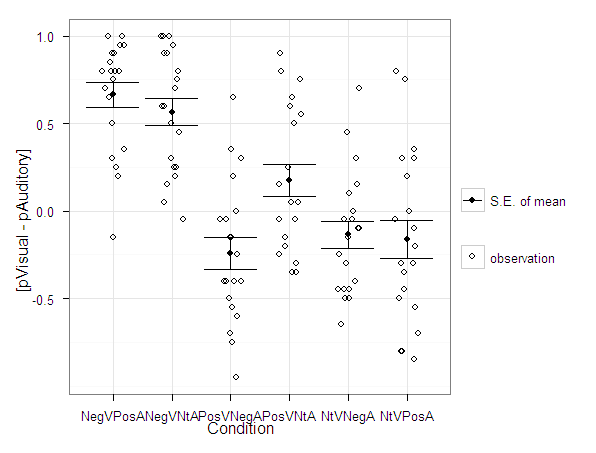

This framework is easily extended to the case where you don’t want a reflection of the same variable, but want to plot the continuous distribution estimate of a second variable. Below is an example, and here I have posted the syntax in entirety used in making this post. In there I also have an example of weighting groups inversely proportional to the total items in each group, which should make the area of each group equal.

In this example of comparing groups, I utilize dots instead of the bar rug, as I believe it provides more contrast between the two distributions. Also note in general I have not superimposed other summary statistics (some of the bean plots have quartile lines super-imposed). You could do this, but it gets a bit busy.