Because my book, LLMs for Mortals, was created with Quarto, it runs the code when I compile the book. It uses cached versions when no code changes, but it is guaranteed to be working code for the parts that have a grey input and a following green output, it is valid code that executed and generated the results.

I try to use temperature zero for most of the book, but some of the parts of the book are stochastic. Reasoning models you cannot set the temperature, so some elements of Chapter 3 introducing the models, and basically all of the section in chapter 6 on agents is stochastic. This actually gave me a better appreciation of some of the unreliability of these models, as for some instances it would fail, and others I needed to recompile because the output was poor.

The way jupyter caching works under the hood, it has a separate cache for the epub and the LaTeX document (that is used for the print version). So you technically get a slightly different book when you purchase epub vs paperback. When you have 60+ failure points per chapter (and that gets doubled when compiling to both epub and PDF), you get to glimpse a few of the warts of the API models.

These are also short snippets, so do not have error catching or more robust JSON parsing, so some of these issues I basically programmed away in production systems at work and did not even notice them. I figured my notes may be useful though in general for others trying to rely on these systems with large volume API calls.

OpenAI

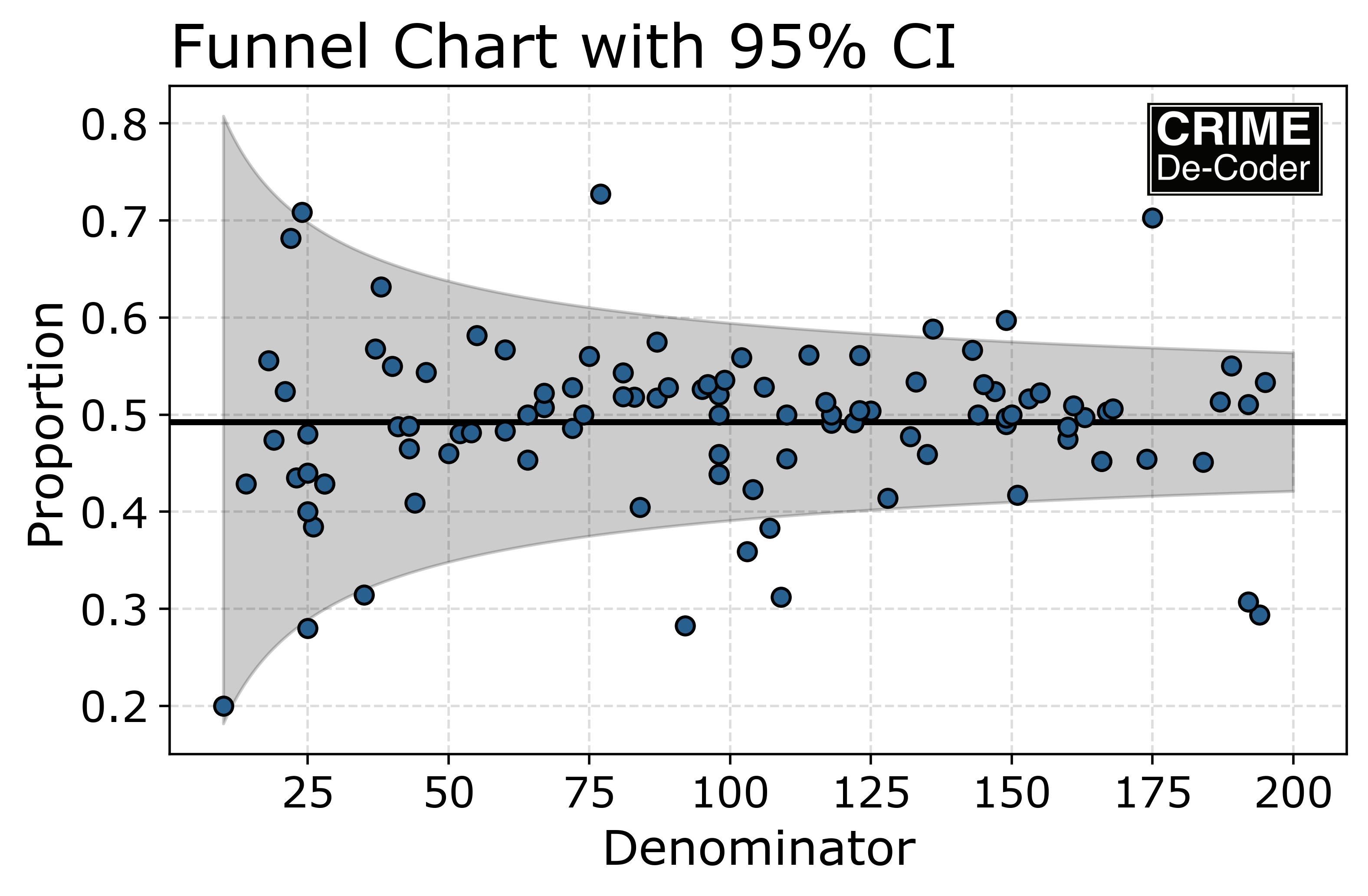

All the models were generally reliable, but one of the examples of stochastic outputs in OpenAI gave me fits – I asked OpenAI to analyze a blog post on my Crime De-Coder site and get information from the post. Now this is a bit tricky, as the reasoning model needs to see the data is not available in the post directly, but in an image.

January 24th, at one point though this became totally unreliable in its output. It would often fail to download the additional image, and when it did, it was pretty inconsistent actually giving an accurate answer.

But now I can run below and this just returns fine and dandy near every time. Here is a loop I ran 5 times and it gives the correct answer (around 160 Tuesday at 4 AM).

from openai import OpenAI

import time

client = OpenAI()

prompt = """

Search <https://crimede-coder.com/blogposts/2024/Aoristic>, what is

the maximum number of commercial burglaries in the chart and on what

day and hour? Do not use shorthand, give an actual number.

If you need to, download additional materials to answer the question.

Be concise in your output.

"""

for _ in range(5):

# minimal reasoning with responses API

response = client.responses.create(

model="gpt-5.2",

reasoning={'effort': 'low'},

tools=[{"type": "web_search"}],

input=prompt,

)

time.sleep(20) # to prevent going over my limit

print(response.output_text)

print('-------------')My only guess is there was some downgrade in the model capabilities, and it routed behind the scenes for the reasoning models to some less capable model. (Just on January 24th though!)

Otherwise, the stochastic examples in the book using OpenAI were pretty reliable.

Anthropic

In the structured outputs chapter, I go through examples of parsing JSON vs progressively building on Pydantic outputs. I actually give examples where Pydantic schema’s can cause some filling in of data that you do not want (if the data should be null, and you use k-shot examples, it will often fill in from your last example).

So this chapter really is a ton of advice on prompt engineering for structured outputs. One example I show is using stop sequences when generating JSON and doing text parsing (which is really not necessary and best practice with Pydantic schemas, but I still use this with AWS Bedrock, since it does not support that yet).

This code works fine, what is inconsistent is that on very rare occasion, Anthropic’s API returns the bracket at the end of the call. This subsequently generates an error with this code, as it is invalid JSON with an extra bracket.

Production systems at the day job use AWS, and I wrote the text parsing in a way I would not even see this error (so not sure if it also happens with AWS). And it was quite rare with Anthropic, I just compiled the book enough times to notice this error happen on a few occasions.

In the book I show off using Google Map grounding, since it is a unique capability of Googles – it was very unreliable. Not unreliable in the sense it would return an error and not be available, but unreliable in “I cannot find any google maps data right now”. So this would compile, I would just need to go look at the output and make sure it actually returned something useful.

You can see I switched to the Vertex API for this example – I cannot confidently say if Vertex was more reliable than the Gemini API for this. I experienced issues with both (maybe slightly fewer with Vertex).

The Anthropic error is not so bad – it causes an actual error in the system. The reasoning and LLM outputs something, but it is not good, troubles me more. We are really just piloting agentic systems at the day gig now with a small number of users – they have not gotten really stress tested by a large number of users. I don’t even want to think about how I would monitor maps grounding in production given my experience.

AWS

AWS I only had one example not consistently work – calling the DeepSeek API.

In the prior code calling Anthropic models via Bedrock, and later chapters I have an example of Mistral and different embedding models (Cohere and Amazon’s Titan), were all fine. Just this single example from DeepSeek would randomly not work. By not work the API would return a response, but the content would be empty. So the final print statement is where the error occurred, accessing text that did not exist.

Most of my work, even if DeepSeek is cheaper, I need to consider caching. So Haiku is pretty competitive with the other models. So I do not have much experience in Bedrock with any models besides Anthropic ones.

My biggest gripe with AWS is the IAM permissions are too difficult (and have changed over the past year). I was able to reasonably figure out how to use S3 Vectors and batch inference (which is discussed in the book). I was able to figure out Knowledge Bases, but I just took it out of the book (both too expensive for hobby projects to have the search endpoint). OpenAI’s vector search store is super easy though, so will definately consider that for traditional RAG applications moving forward.

Buy the book!

Use promo code LLMDEVS for 50% off of the epub. Or if you prefer purchase the paperback.