Ashely Evan’s writes in with a question:

I very recently started looking into clustering which I’ve only touched upon briefly in the past.

I have an unusual dataset, with dichotomous or binary responses for around 25000 patents and 35 categories.

Would you be able to recommend a suitable method, I couldn’t see if you’d done anything like this before on your site.

It’s a similar situation to a survey with 25000 respondents and 35 questions which can only be answered yes/no (1 or 0 is how I’ve represented this in my data).

The motivation for clustering would be to identify which questions/areas naturally cluster together to create distinct profiles and contrast differences.

I tried the k modes algorithm in r, using an elbow method which identified 3 clusters. This is a decent starting point, the size of the clusters are quite unbalanced, two had one common category for every result and the other category was quite fragmented.

I figured this topic would be a good one for the blog. The way clustering is treated in many data analysis courses is very superficial, so this contains a few of my thoughts to help people in conducting real world cluster analysis.

I have never done any project with similar data. So caveat emptor on advice!

So first, clustering can be tricky, since it is very exploratory. If you can put more clear articulation what the end goal is, I always find that easier. Clustering will always spit out solutions, but having clear end-goals makes it easier to tell whether the clustering has any face validity to accomplish those tasks. (And sometimes people don’t want clustering, they want supervised learning or anomaly detection.) What is the point of the profiles? Do you have outcomes you expect with them (like people do in market segmentation)?

The clustering I have done is geospatial – I like a technique called DBSCAN – this is very different than K-means (which every point is assigned into a cluster). You just identify areas of many cases nearby in space, and if this area has greater than some threshold, it is a local cluster. K-means being uneven is typical, as every point needs to be in a cluster. You tend to have a bunch of junk points in the cluster (so sometimes focusing on the mean or modal point in k-means may be better than looking at the whole distribution).

I don’t know if DBSCAN makes sense though for 0/1 data. Another problem with clustering many variables is what is called the curse of dimensionality. If you have 3 variables, you can imagine drawing your 3d scatterplot and clustering of those points in that 3d space. You cannot physically imagine it, but clustering with more variables is like this visualization, but in many higher dimensions.

What happens though is that in higher dimensions, all of the points get pushed away from each other, and closer to the hull of the that k-dimensional sphere (or I should say box here with 0/1 data). So the points tend to be equally far apart, and so clusters are not well defined. This is a different problem, but I like this example of averaging different dimensions to make a pilot that does not exist, it is the same issue.

There may be ways to take your 35 inputs and reduce down to fewer variables (the curse of dimensionality comes at you fast – binary variables may not be as problematic as continuous ones, but it is a big deal for even as few as 6-10 dimensions).

So random things to look into:

factor analysis of dichotomous variables (such as ordination analysis), or simply doing PCA on the columns may identify redundant columns (this doesn’t get you row wise clusters, but PCA followed by K-means is a common thing people do). Note that this only applies to independent categories, turning a single category into 35 dummy variables and then doing PCA does not make sense.

depending on what you want, looking at association rules/frequent item sets may be of interest. So that is identifying cases that tend to cluster with pairs of attributes.

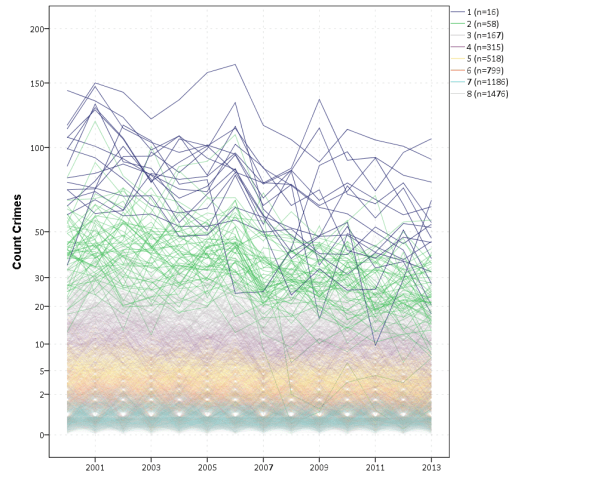

for just looking at means of different profiles, latent class analysis I think is the “best” approach out of the box (better than k-means). But it comes with its own problems of selecting the number of groups.

The regression + mixture model I think is a better way to view clustering in a wider variety of scenarios, such as customer segmentation. I really do not like k-means, I think it is a bad default for many real world scenarios. But that is what most often gets taught in data science courses.

The big thing is though you need to be really clear about what the goals of the analysis are – those give you ways to evaluate the clustering solutions (even if those criteria are only fuzzy).