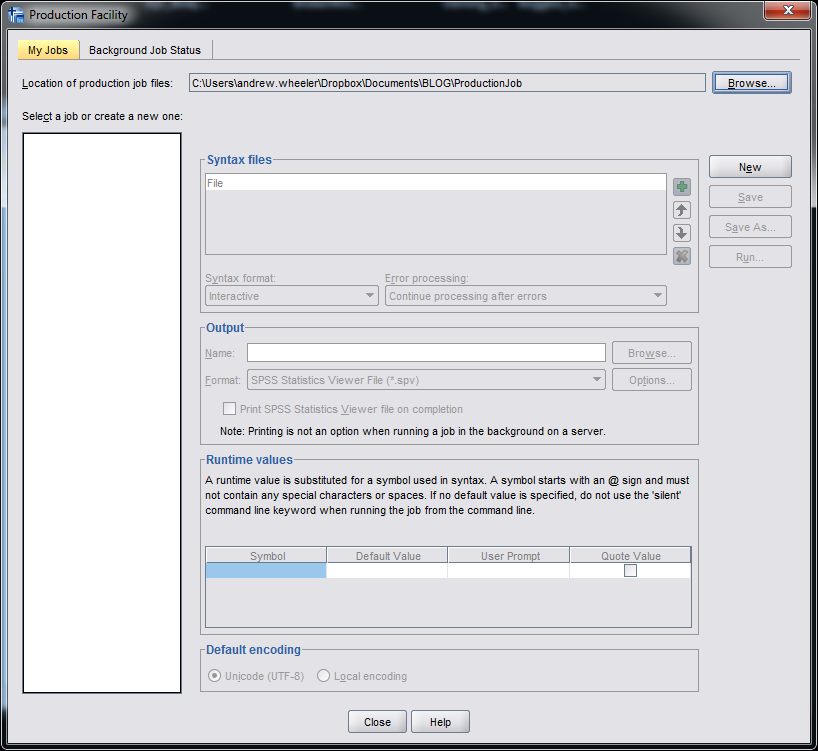

The other day I noticed when making the labels for treemaps that when using a polygon element in inline GPL SPSS places the label directly on the centroid. This is opposed to offsetting the label when using a point element. We can use this to our advantage to force labels in plots to be exactly where we want them. (Syntax to replicate all of this here.)

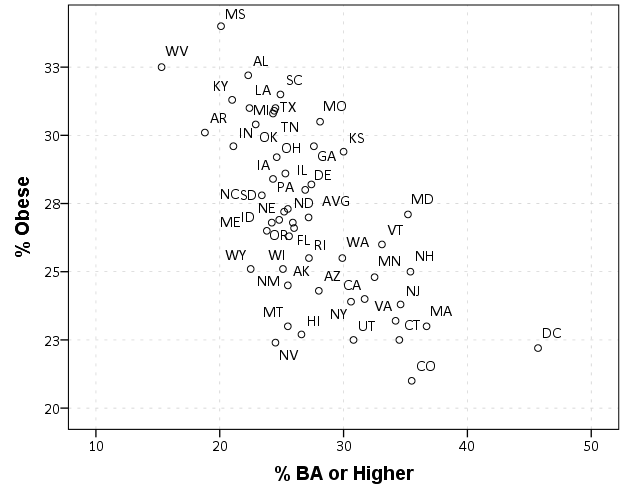

One popular example I have seen is in state level data to use the state abbreviation in a scatterplot instead of a point. Here is an example using the college degree and obesity example originally via Albert Cairo.

FILE HANDLE save /NAME = "!!!!Your Handle Here!!!".

*Data obtained from http://vizwiz.blogspot.com/2013/01/alberto-cairo-three-steps-to-become.html

*Data was originally from VizWiz blog https://dl.dropbox.com/u/14050515/VizWiz/obesity_education.xls.

*That link does not work anymore though, see https://www.dropbox.com/s/lfwx7agkraci21y/obesity_education.xls?dl=0.

*For my own dropbox link to the data.

GET DATA /TYPE=XLS

/FILE='save\obesity_education.xls'

/SHEET=name 'Sheet1'

/CELLRANGE=full

/READNAMES=on

/ASSUMEDSTRWIDTH=32767.

DATASET NAME Obs.

MATCH FILES FILE = *

/DROP V5.

FORMATS BAORHIGHER OBESITY (F2.0).

*Scatterplot with States and labels.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=BAORHIGHER OBESITY StateAbbr

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: BAORHIGHER=col(source(s), name("BAORHIGHER"))

DATA: OBESITY=col(source(s), name("OBESITY"))

DATA: StateAbbr=col(source(s), name("StateAbbr"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("% BA or Higher"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("% Obese"))

ELEMENT: point(position(BAORHIGHER*OBESITY), label(StateAbbr))

END GPL.

Here you can see the state abbreviations are off-set from the points. A trick to just plot the labels, but not the points, is to draw the points fully transparent. See the transparency.exterior(transparency."1") in the ELEMENT statement.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=BAORHIGHER OBESITY StateAbbr

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: BAORHIGHER=col(source(s), name("BAORHIGHER"))

DATA: OBESITY=col(source(s), name("OBESITY"))

DATA: StateAbbr=col(source(s), name("StateAbbr"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("% BA or Higher"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("% Obese"))

ELEMENT: point(position(BAORHIGHER*OBESITY), label(StateAbbr),

transparency.exterior(transparency."1"))

END GPL.

But, this does not draw the label exactly at the data observation. You can post-hoc edit the chart to specify that the label is drawn at the middle of the point element, but another option directly in code is to specify the element as a polygon instead of a point. By default this is basically equivalent to using a point element, since we do not pass the function an actual polygon using the link.??? functions.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=BAORHIGHER OBESITY StateAbbr

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: BAORHIGHER=col(source(s), name("BAORHIGHER"))

DATA: OBESITY=col(source(s), name("OBESITY"))

DATA: StateAbbr=col(source(s), name("StateAbbr"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("% BA or Higher"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("% Obese"))

ELEMENT: polygon(position(BAORHIGHER*OBESITY), label(StateAbbr), transparency.exterior(transparency."1"))

END GPL.

To show that this now places the labels directly on the data values, here I superimposed the data points as red dots over the labels.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=BAORHIGHER OBESITY StateAbbr

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: BAORHIGHER=col(source(s), name("BAORHIGHER"))

DATA: OBESITY=col(source(s), name("OBESITY"))

DATA: StateAbbr=col(source(s), name("StateAbbr"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("% BA or Higher"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("% Obese"))

ELEMENT: polygon(position(BAORHIGHER*OBESITY), label(StateAbbr), transparency.exterior(transparency."1"))

ELEMENT: point(position(BAORHIGHER*OBESITY), color.interior(color.red))

END GPL.

Note to get the labels like this my chart template specifies the style of data labels as:

<!-- Custom data labels for points -->

<setGenericAttributes elementName="labeling" parentName="point" count="0" styleName="textFrameStyle" color="transparent" color2="transparent"/>

The first style tag specifies the font, and the second specifies the background color and outline (my default was originally a white background with a black outline). The option styleOnly="true" makes it so the labels are not always generated in the chart. Another side-effect of using a polygon element I should note is that SPSS draws all of the labels. When labelling point elements SPSS does intelligent labelling, and does not label all of the points if many overlap (and tries to place the labels at non-overlapping locations). It is great for typical scatterplots, but here I do not want that behavior.

Other examples I think this would be useful are for simple dot plots in which the categories have meaningful labels. Here is an example using a legend, and one has to learn the legend to understand the graph. I like making the points semi-transparent, so when they overlap you can still see the different points (see here for an example with data that actually overlap).

Such a simple graph though we can plot the category labels directly.

The direct labelling will not work out so well if if many of the points overlap, but jittering or dodging can be used then as well. (You will have to jitter or dodge the data yourself if using a polygon element in inline GPL. If you want to use a point element again you can post hoc edit the chart so that the labels are at the middle of the point.)

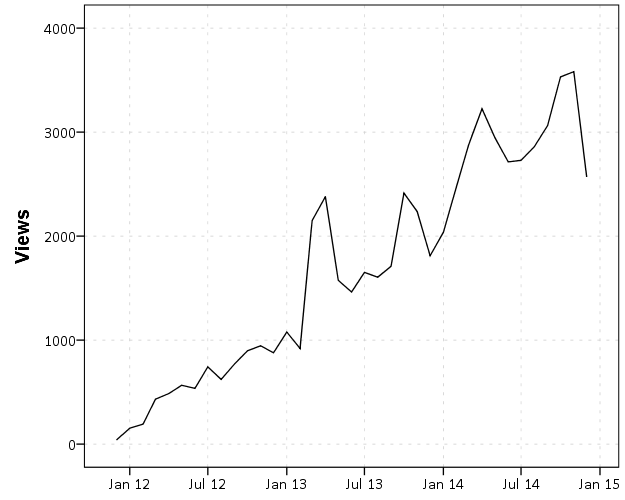

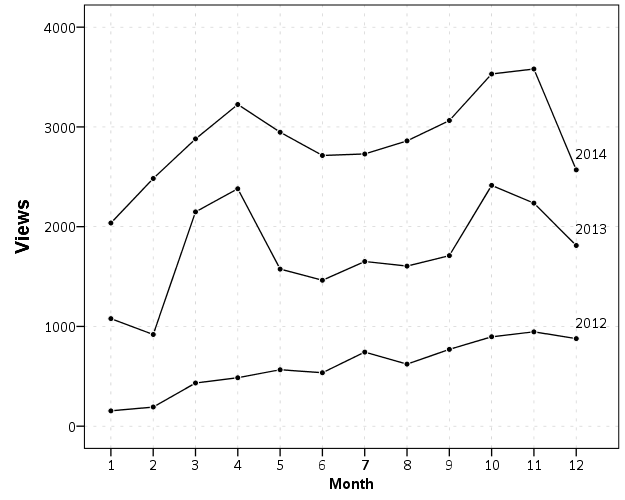

Another example is that I like to place labels in line graphs at the end of the line. Here I show an example of doing that by making a separate label for only the final value of the time series, offsetting to the right slightly, and then placing the invisible polygon element in the chart.

SET SEED 10.

INPUT PROGRAM.

LOOP #M = 1 TO 5.

LOOP T = 1 TO 10.

COMPUTE ID = #M.

COMPUTE Y = RV.NORMAL(#M*5,1).

END CASE.

END LOOP.

END LOOP.

END FILE.

END INPUT PROGRAM.

DATASET NAME TimeSeries.

FORMATS T ID Y (F3.0).

ALTER TYPE ID (A1).

STRING Lab (A1).

IF T = 10 Lab = ID.

EXECUTE.

*Labelled at end of line.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=T Y ID Lab MISSING=VARIABLEWISE

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: T=col(source(s), name("T"))

DATA: Y=col(source(s), name("Y"))

DATA: ID=col(source(s), name("ID"), unit.category())

DATA: Lab=col(source(s), name("Lab"), unit.category())

TRANS: P=eval(T + 0.2)

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("T"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Y"))

SCALE: linear(dim(1), min(1), max(10.2))

ELEMENT: line(position(T*Y), split(ID))

ELEMENT: polygon(position(P*Y), label(Lab), transparency.exterior(transparency."1"))

END GPL.This works the same for point elements too, but this forces the label to be drawn and they are drawn at the exact location. See the second image in my peremptory challenge post for example behavior when labelling with the point element.

You can also use this to make random annotations in the graph. Code omitted here (it is available in the syntax at the beginning), but here is an example:

If you want you can then style this label separately when post-hoc editing the chart. Here is a silly example. (The workaround to use annotations like this suggests a change to the grammar to allow GUIDES to have a special type specifically for just a label where you supply the x and y position.)

This direct labelling just blurs the lines between tables and graphs some more, what Tukey calls semi-graphic. I recently came across the portmanteau, grables (graphs and tables) to describe such labelling in graphs as well.

Musings on Comments

I recently posted a comment policy. I do not get that many comments now, but I did delete a comment recently asking for help on a code sample, so figured it would be worth elaborating on.

Comments are great, and I hope to get more, but with my participation on the stack exchange sites (and commenting on other blogs) I definitely see the need to take active moderation. This is not a big deal for the site so far (I rarely post anything controversial) but is really necessary for any blog generating a lot of comments.

My position is not quite extreme as Ed Tufte, e.g. I don’t plan on deleting a comment if I don’t like the content enough, but I will definitely delete off-topic comments and anything I find offensive. My position is more in line with Jeff Atwood’s thoughts, who discusses the topic quite a bit on his coding horror blog (see here for one example).

Basically the comments take curation, just like any site or wiki. Comments without moderation in any substantive amount (e.g. YouTube, many news articles) are simply not worth reading. The same moderation is what makes the stack exchange sites so much better than email list-serves, and the lack of moderation is what makes some MOOC forums so chaotic.

Posted by Andy Wheeler on December 7, 2014

https://andrewpwheeler.com/2014/12/07/musings-on-comments/