Recently on the Crime Analysis sub-reddit an individual posted about working with an AI product company developing a tool for detectives or investigators.

The Mercor platform has many opportunities that may be of interest to my network, so I am sharing them here. These include not only for investigators, but GIS analysts, writers, community health workers, etc. (The eligibility interviewers I think if you had any job in gov services would likely qualify, it is just reviewing questions.)

All are part time (minimum of 15 hours per week), remote, and can be in the US, Canada, or UK. (But cannot support H1-B or OPT visas in the US).

Additional for professionals looking to get into the tech job market, see these two resources:

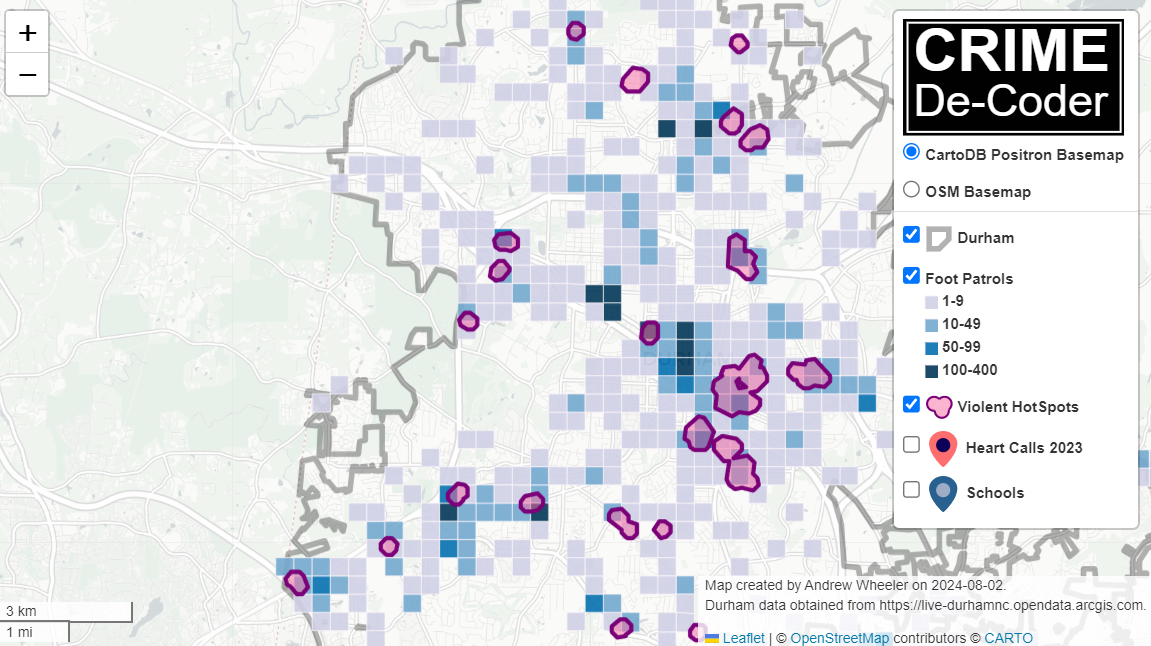

I actually just hired my first employee at Crime De-Coder. Always feel free to reach out if you think you would be a good fit for the types of applications I am working on (python, GIS, crime analysis experience). I will put you in the list to reach out to when new opportunities are available.

Detectives and Criminal Investigators

$65-$115 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Detectives and Criminal Investigators to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Detective and Criminal Investigator. Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum of 15 hours per week

Community Health Workers

$60-$80 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Community Health Workers to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Community Health Worker. Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum 15 hours per week

Writers and Authors

$60-$95 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Writers and Authors to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Writer and Author.

Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum 15 hours per week

Eligibility Interviewers, Government Programs

$60-$80 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Eligibility Interviewers, Government Programs to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Eligibility Interviewers, Government Program. Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum 15 hours per week

Cartographers and Photogrammetrists

$60-$105 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Cartographers and Photogrammetrists to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Cartographer and Photogrammetrist. Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum 15 hours per week

Geoscientists, Except Hydrologists and Geographers

$85-$100 hourly

Mercor is recruiting Geoscientists, Except Hydrologists and Geographers to work on a research project for one of the world’s top AI companies. This project involves using your professional experience to design questions related to your occupation as a Geoscientists, Except Hydrologists and Geographers Applicants must:

- Have 4+ years full-time work experience in this occupation;

- Be based in the US, UK, or Canada

- minimum of 15 hours per week