I debated on pulling an Andrew Gelman and adding a ps to my prior Junk Charts Challenge post, but it ended up being too verbose, so I just made an entirely new follow-up. To start, the discussion has currently evolved from this series of posts;

- The original post on remaking a great line chart by Kaiser Fung, with the suggestion that the task (data manipulation and graphing) is easier in Excel.

- My response on how to make the chart in SPSS.

- Kaiser’s response to my post, in which I doubt I swayed his opinion on using Excel for this task! It appears to me based on the discussion so far the only real quarrel is whether the data manipulation is sufficiently complicated enough compared to the ease of pointing and clicking in Excel to justify using Excel. In SPSS to recreate Kaiser’s chart is does take some advanced knowledge of sorting and using lags to identify the pit and recoveries (the same logic could be extended to the data manipulations Kaiser says I skim over, as long as you can numerically or externally define what is a start of a recession).

All things considered for the internet, discussion has been pretty cordial so far. Although it is certainly sprinkled in my post, I didn’t mean for my post on SPSS to say that the task of grabbing data from online, manipulating it, and creating the graph was in any objective way easier in SPSS than in Excel. I realize pointing-and-clicking in Excel is easier for most, and only a few really adept at SPSS (like myself) would consider it easier in SPSS. I write quite a few tutorials on how to do things in SPSS, and that was one of the motivations for the tutorial. I want people using SPSS (or really any graphing software) to make nice graphs – and so if I think I can add value this way to the blogosphere I will! I hope my most value added is through SPSS tutorials, but I try to discuss general graphing concepts in the posts as well, so even for those not using SPSS it hopefully has some other useful content.

My original post wasn’t meant to discuss why I feel SPSS is a better job for this particular task, although it is certainly a reasonable question to ask (I tried to avoid it to prevent flame wars to be frank – but now I’ve stepped in it at this point it appears). As one of the comments on Kaiser’s follow up notes (and I agree), some tools are better for some jobs and we shouldn’t prefer one tool because of some sort of dogmatic allegiance. To make it clear though, and it was part of my motivation to write my initial response to the challenge post, I highly disagree that this particular task, which entails grabbing data from the internet, manipulating it, and creating a graph, and updating said graph on a monthly basis is better done in Excel. For a direct example of my non-allegiance to doing everything in SPSS for this job, I wouldn’t do the grabbing the data from the internet part in SPSS (indeed – it isn’t even directly possible unless you use Python code). Assuming it could be fully automated, I would write a custom SPSS job that manipulates the data after a wget command grabs the data, and have it all wrapped up in one bat file that runs on a monthly timer.

To go off on a slight tangent, why do I think I’m qualified to make such a distinction? Well, I use both SPSS and Excel on a regular basis. I wouldn’t consider myself a wiz at Excel nor VBA for Excel, but I have made custom Excel MACROS in the past to perform various jobs (make and format charts/tables etc.), and I have one task (a custom daily report of the crime incidents reported the previous day) I do on a daily basis at my job in Excel. So, FWIW, I feel reasonably qualified to make decisions on what tasks I should perform in which tools. So I’m giving my opinion, the same way Kaiser gave his initial opinion. I doubt my experience is as illustruous as Kaiser’s, but you can go to my CV page to see my current and prior work roles as an analyst. If I thought Excel, or Access, or R, or Python, or whatever was a better tool I would certainly personally use and suggest that. If you don’t have alittle trust in my opinion on such matters, well, you shouldn’t read what I write!

So, again to be clear, I feel this is a job better for SPSS (both the data manipulation and creating the graphics), although I admit it is initially harder to write the code to accomplish the task than pointing, clicking and going through chart wizards in Excel. So here I will try to articulate those reasons.

- Any task I do on a regular basis, I want to be as automated as possible. Having to point-click, copy-paste on a regular basis invites both human error and is a waste of time. I don’t doubt you could fully (or very near) automate the task in Excel (as the comment on my blog post mentions). But this will ultimately involve scripting in VBA, which diminishes in any way that the Excel solution is easier than the SPSS solution.

- The breadth of both data management capabilities, statistical analysis, and graphics are much larger in SPSS than in Excel. Consider the VBA code necessary to replicate my initial

VARSTOCASEScommand in Excel, that is reshaping wide data to stacked long form. Consider the necessary VBA code to execute summary statistics over different groups without knowing what the different groups are beforehand. These are just a sampling of data management tools that are routine in statistics packages. In terms of charting, the most obvious function lacking in Excel is that it currently does not have facilities to make small-multiple charts (you can see some exceptional hacks from Jon Peltier, but those are certainly more limited in functionality that SPSS). Not mentioned (but most obvious) is the statistical capabilities of a statistical software!

So certainly, this particular job, could be done in Excel, as it does not require any functionality unique to a stats package. But why hamstring myself with these limitations from the onset? Frequently after I build custom, routine analysis like this I continually go back and provide more charts, so even if I have a good conceptualization of what I want to do at the onset there is no guarantee I won’t want to add this functionality in later. In terms of charting not having flexible small multiple charts is really a big deal, they can be used all the time.

Admittedly, this job is small enough in scope, if say the prior analyst was doing a regular updated chart via copy-paste like Kaiser is suggesting, I would consider just keeping that same format (it certainly is a lost opportunity cost to re-write the code in SPSS, and the fact that it is only on a monthly basis means to get time recovered if the task were fully automated would take quite some time). I just have personally enough experience in SPSS I know I could script a solution in SPSS quicker from the on-set than in Excel (I certainly can’t extrapolate that to anyone else though).

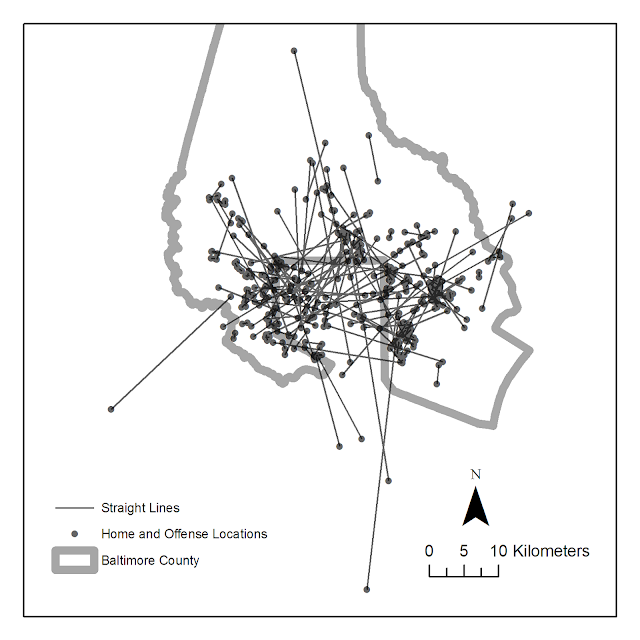

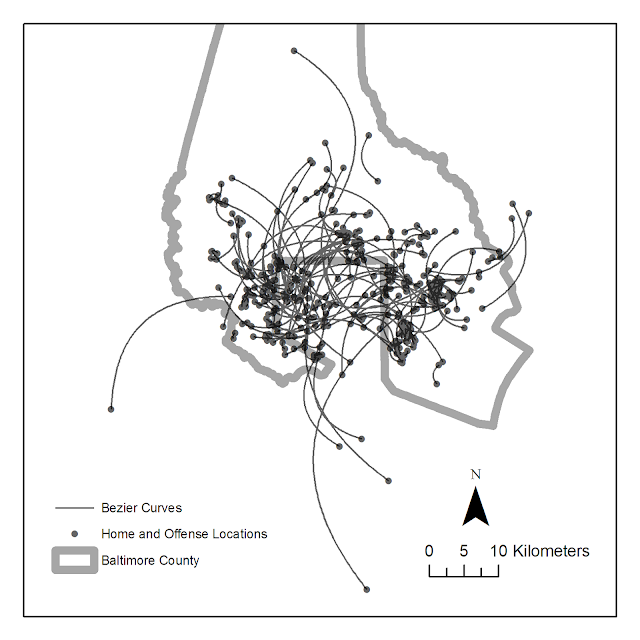

Part of both my preference and experience in SPSS comes from the jobs I personally have to do. For an example, I routinely pull a database of 500,000 incidents, do some data cleaning, and then merge this to a table of 300,000 charges and offenses and then merge to a second table of geocoded incident locations. Then using this data I routinely subset it, create aggregate summaries, tables, estimate various statistics and models, make some rudimentary maps, or even export the necessary data to import into a GIS software.

For arguments sake (with the exception of some of the more complicated data cleaning) this could be mostly done in SQL – but certainly no reasonable person should consider doing these multiple table merges and data cleaning in Excel (the nice interactive facilities with working with the spreadsheet in Excel are greatly dimished with any tables that take more a few scrolls to see). Statistical packages are really much more than tools to fit models, they are tools for working and manipulating data. I would highly recommend if you have to conduct routine tasks in which you manipulate data (something I assume most analysts have to do) you should consider learning statistical sofware, the same way I would recommend you should get to know SQL.

To be more balanced, here are things (knowing SPSS really well and Excel not as thoroughly) I think Excel excels at compared to SPSS;

- Ease of making nicely formatted tables

- Ease of directly interacting and editing components of charts and tables (this includes adding in supplementary vector graphics and labels).

- Sparklines

- Interactive Dashboards/Pivot Tables

Routine data management is not one of them, and only really sparklines and interactive dashboards are functionality in which I would prefer to make an end product in Excel over SPSS (and that doesn’t mean the whole workflow needs to be one software). I clean up ad-hoc tables for distribution in Excel all the time, because (as I said above) editing them in Excel is easier than editing them in SPSS. Again, my opinion, FWIW.