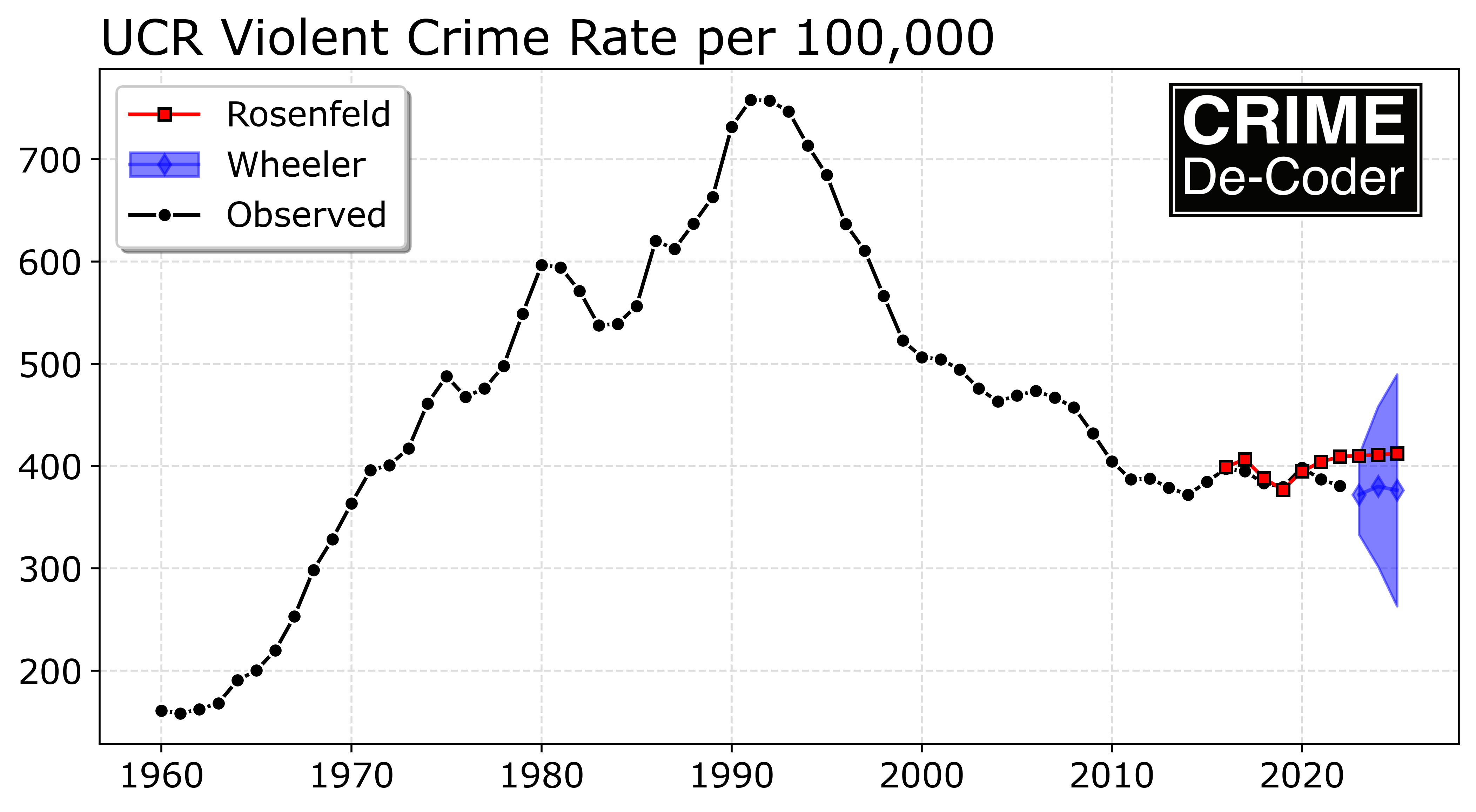

Richard Rosenfeld in the most recent Criminologist published a piece about forecasting national level crime rates. People complain about the FBI releasing crime stats a year late, academics are worse; Richard provided “forecasts” for 2021 through 2025 for an article published in late 2023.

Even ignoring the stalecasts that Richard provided – these forecasts had/have no chance of being correct. Point forecasts will always be wrong – a more reasonable approach is to provide the prediction intervals for the forecasts. Showing error intervals around the forecasts will show how Richard interpreting minor trends is likely to be misleading.

Here I provide some analysis using ARIMA models (in python), to illustrate what reasonable forecast error looks like in this scenario, code and data on github.

You can get the dataset on github, but just some upfront with loading the libraries I need and getting the data in the right format:

import pandas as pd

from statsmodels.tsa.arima.model import ARIMA

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# via https://www.disastercenter.com/crime/uscrime.htm

ucr = pd.read_csv('UCR_1960_2019.csv')

ucr['VRate'] = (ucr['Violent']/ucr['Population'])*100000

ucr['PRate'] = (ucr['Property']/ucr['Population'])*100000

ucr = ucr[['Year','VRate','PRate']]

# adding in more recent years via https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/docApi

# I should use original from counts/pop, I don't know where to find those though

y = [2020,2021,2022]

v = [398.5,387,380.7]

p = [1958.2,1832.3,1954.4]

ucr_new = pd.DataFrame(zip(y,v,p),columns = list(ucr))

ucr = pd.concat([ucr,ucr_new],axis=0)

ucr.index = pd.period_range(start='1960',end='2022',freq='A')

# Richard fits the model for 1960 through 2015

train = ucr.loc[ucr['Year'] <= 2015,'VRate']Now we are ready to fit our models. To make it as close to apples-to-apples as Richard’s paper, I just fit an ARIMA(1,1,2) model – I do not do a grid search for the best fitting model (also Richard states he has exogenous factors for inflation in the model, which I do not here). Note Richard says he fits an ARIMA(1,0,2) for the violent crime rates in the paper, but he also says he differenced the data, which is an ARIMA(1,1,2) model:

# Not sure if Richard's model had a trend term, here no trend

violent = ARIMA(train,order=(1,1,2),trend='n').fit()

violent.summary()This produces the output:

SARIMAX Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: VRate No. Observations: 56

Model: ARIMA(1, 1, 2) Log Likelihood -242.947

Date: Sun, 19 Nov 2023 AIC 493.893

Time: 19:33:53 BIC 501.923

Sample: 12-31-1960 HQIC 496.998

- 12-31-2015

Covariance Type: opg

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ar.L1 -0.4545 0.169 -2.688 0.007 -0.786 -0.123

ma.L1 1.1969 0.131 9.132 0.000 0.940 1.454

ma.L2 0.7136 0.100 7.162 0.000 0.518 0.909

sigma2 392.5640 104.764 3.747 0.000 187.230 597.898

===================================================================================

Ljung-Box (L1) (Q): 0.13 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.82

Prob(Q): 0.72 Prob(JB): 0.67

Heteroskedasticity (H): 0.56 Skew: -0.06

Prob(H) (two-sided): 0.23 Kurtosis: 2.42

===================================================================================So some potential evidence of over-differencing (with the negative AR(1) coefficient). Looking at violent.test_serial_correlation('ljungbox') there is no significant serial auto-correlation in the residuals. One could use some sort of auto-arima approach to pick a “better” model (it clearly needs to be differenced at least once, also maybe should also be modeling the logged rate). But there is not much to squeeze out of this – pretty much all of the ARIMA models will produce very similar forecasts (and error intervals).

So in the statsmodels package, you can append new data and do one step ahead forecasts, so this is comparable to Richard’s out of sample one step ahead forecasts in the paper for 2016 through 2020:

# To make it apples to apples, only appending through 2020

av = (ucr['Year'] > 2015) & (ucr['Year'] <= 2020)

violent = violent.append(ucr.loc[av,'VRate'], refit=False)

# Now can show insample predictions and forecasts

forecast = violent.get_prediction('2016','2025').summary_frame(alpha=0.05)If you print(forecast) below are the results. One of the things I want to note is that if you do one-step-ahead forecasts, here the years 2016 through 2020, the standad error is under 20 (this is well within Richard’s guesstimate to be useful it needs to be under 10% absolute error). When you start forecasting multiple years ahead though, the error compounds over time. So to forecast 2022, you need a forecast of 2021. To forecast 2023, you need to forecast 21,22 and then 23, etc.

VRate mean mean_se mean_ci_lower mean_ci_upper

2016 397.743461 19.813228 358.910247 436.576675

2017 402.850827 19.813228 364.017613 441.684041

2018 386.346157 19.813228 347.512943 425.179371

2019 379.315712 19.813228 340.482498 418.148926

2020 379.210158 19.813228 340.376944 418.043372

2021 412.990860 19.813228 374.157646 451.824074

2022 420.169314 39.803285 342.156309 498.182318

2023 416.906654 57.846105 303.530373 530.282936

2024 418.389557 69.535174 282.103120 554.675994

2025 417.715567 80.282625 260.364513 575.066620The standard error scales pretty much like sqrt(steps*se^2) (it is additive in the variance). Richard’s forecasts do better than mine for some of the point estimates, but they are similar overall:

# Richard's estimates

forecast['Rosenfeld'] = [399.0,406.8,388.0,377.0,394.9] + [404.1,409.3,410.2,411.0,412.4]

forecast['Observed'] = ucr['VRate']

forecast['MAPE_Andy'] = 100*(forecast['mean'] - forecast['Observed'])/forecast['Observed']

forecast['MAPE_Rick'] = 100*(forecast['Rosenfeld'] - forecast['Observed'])/forecast['Observed']And this now shows for each of the models:

VRate mean mean_ci_lower mean_ci_upper Rosenfeld Observed MAPE_Andy MAPE_Rick

2016 397.743461 358.910247 436.576675 399.0 397.520843 0.056002 0.372095

2017 402.850827 364.017613 441.684041 406.8 394.859716 2.023785 3.023931

2018 386.346157 347.512943 425.179371 388.0 383.362999 0.778155 1.209559

2019 379.315712 340.482498 418.148926 377.0 379.421097 -0.027775 -0.638103

2020 379.210158 340.376944 418.043372 394.9 398.500000 -4.840613 -0.903388

2021 412.990860 374.157646 451.824074 404.1 387.000000 6.715985 4.418605

2022 420.169314 342.156309 498.182318 409.3 380.700000 10.367563 7.512477

2023 416.906654 303.530373 530.282936 410.2 NaN NaN NaN

2024 418.389557 282.103120 554.675994 411.0 NaN NaN NaN

2025 417.715567 260.364513 575.066620 412.4 NaN NaN NaNSo MAPE in the held out sample does worse than Rick’s models for the point estimates, but look at my prediction intervals – the observed values are still totally consistent with the model I have estimated here. Since this is a blog and I don’t need to wait for peer review, I can however update my forecasts given more recent data.

# Given updated data until end of series, lets do 23/24/25

violent = violent.append(ucr.loc[ucr['Year'] > 2020,'VRate'], refit=False)

updated_forecast = violent.get_forecast(3).summary_frame(alpha=0.05)And here are my predictions:

VRate mean mean_se mean_ci_lower mean_ci_upper

2023 371.977798 19.813228 333.144584 410.811012

2024 380.092102 39.803285 302.079097 458.105106

2025 376.404091 57.846105 263.027810 489.780373You really need to graph these out to get a sense of the magnitude of the errors:

Note how Richard’s 2021 and 2022 forecasts and general increasing trend have already been proven to be wrong. But it really doesn’t matter – any reasonable model that admitted uncertainty would never let one reasonably interpret minor trends over time in the way Richard did in the criminologist article to begin with (forecasts for ARIMA models are essentially mean-reverting, they will just trend to a mean term in a short number of steps). Richard including exogenous factors actually makes this worse – as you need to forecast inflation and take that forecast error into account for any multiple year out forecast.

Richard has consistently in his career overfit models and subsequently interpreted the tea leaves in various macro level correlations (Rosenfeld, 2018). His current theory of inflation and crime is no different. I agree that forecasting is the way to validate criminological theories – picking up a new pet theory every time you are proven wrong though I don’t believe will result in any substantive progress in criminology. Most of the short term trends criminologists interpret are simply due to normal volatility in the models over time (Yim et al., 2020). David McDowall has a recent article that is much more measured about our cumulative knowledge of macro level crime rate trends – and how they can be potentially related to different criminological theories (McDowall, 2023). Matt Ashby has a paper that compares typical errors for city level forecasts – forecasting several years out tends to product quite inaccurate estimates, quite a bit larger than Richard’s 10% is useful threshold (Ashby, 2023).

Final point that I want to make is that honestly it doesn’t even matter. Richard can continue to keep making dramatic errors in macro level forecasts – it doesn’t matter if he publishes estimates that are two+ years old and already wrong before they go into print. Because unlike what Richard says – national, macro level violent crime forecasts do not help policy response – why would Pittsburgh care about the national level crime forecast? They should not. It does not matter if we fit models that are more accurate than 5% (or 1%, or whatever), they are not helpful to folks on the hill. No one is sitting in the COPS office and is like “hmm, two years from now violent crime rates are going up by 10, lets fund 1342 more officers to help with that”.

Richard can’t have skin the game for his perpetual wrong macro level crime forecasts – there is no skin to have. I am a nerd so I like looking at numbers and fitting models (or here it is more like that XKCD comic of yelling at people on the internet). I don’t need to make up fairy tale hypothetical “policy” applications for the forecasts though.

If you want a real application of crime forecasts, I have estimated for cities that adding an additional home or apartment unit increases the number of calls per service by about 1 per year. So for growing cities that are increasing in size, that is the way I suggest to make longer term allocation plans to increase police staffing to increase demand.

References

-

Ashby, M. (2023). Forecasting crime trends to support police strategic decision making. CrimRxiv.

-

McDowall, D. (2023). Empirical Properties of Crime Rate Trends. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 10439862231189979.

-

Rosenfeld, R. (2018). Studying crime trends: Normal science and exogenous shocks. Criminology, 56(1), 5-26.

-

Yim, H. N., Riddell, J. R., & Wheeler, A. P. (2020). Is the recent increase in national homicide abnormal? Testing the application of fan charts in monitoring national homicide trends over time. Journal of Criminal Justice, 66, 101656.