Bruce Weaver on the SPSS Nabble site pointed out that the Centre for Multilevel Modelling has added some syntax files for multilevel modelling for SPSS. I went through the tutorials (in R and Stata) a few years ago and would highly recommend them.

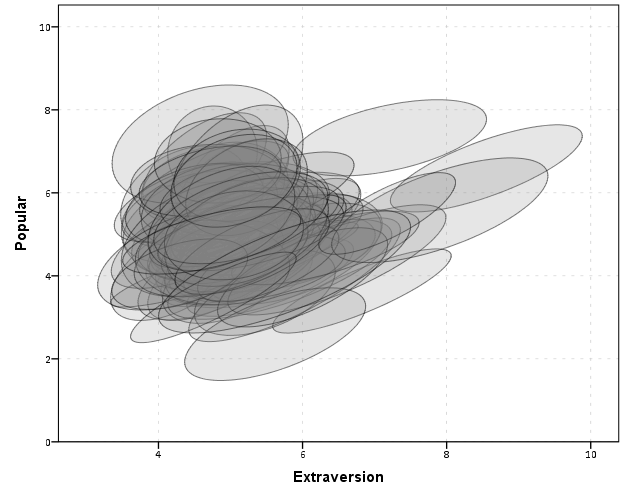

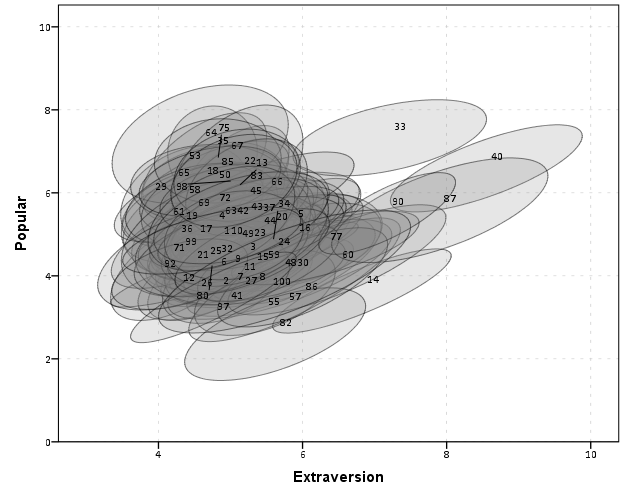

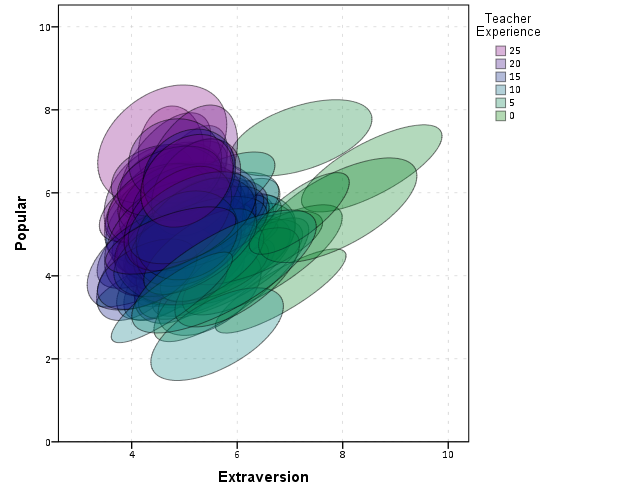

Somehow following the link trail I stumbled on this white paper, Visualising multilevel models; The initial analysis of data, by John Bell and figured it would be good fodder for the the blog. Bell basically shows how using smoothed regression estimates within groups is a good first step in data analysis of complicated multi-level data. I obviously agree, and previously showed how to use ellipses to the same effect. The plots in the Bell whitepaper though are very easy to replicate directly in base SPSS syntax (no extra stat modules or macros required) using just GGRAPH and inline GPL.

For illustration purposes, I will use the same data as I did to illustrate ellipses. It is the popular2.sav sample from Joop Hox’s book. So onto the SPSS code; first we will define a FILE HANDLE for where the popular2.sav data is located and open that file.

FILE HANDLE data /NAME = "!!!!!!Your Handle Here!!!!!".

GET FILE = "data\popular2.sav".

DATASET NAME popular2.Now, writing the GGRAPH code that will follow is complicated. But we can use the GUI to help us write the most of it and them edit the pasted code to get the plot we want in the end. So, the easiest start to get the graph with the regression lines we want in the end is to navigate to the chart builder menu (Graphs -> Chart Builder), and then create a scatterplot with extrav on the x axis, popular on the y axis, and use class to color the points. The image below is a screen shot of this process, and below that is the GGRAPH code you get when you paste the syntax.

*Base plot created from GUI.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=extrav popular class[LEVEL=NOMINAL] MISSING=LISTWISE

REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: extrav=col(source(s), name("extrav"))

DATA: popular=col(source(s), name("popular"))

DATA: class=col(source(s), name("class"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("extraversion"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("popularity sociometric score"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.exterior), label("class ident"))

ELEMENT: point(position(extrav*popular), color.exterior(class))

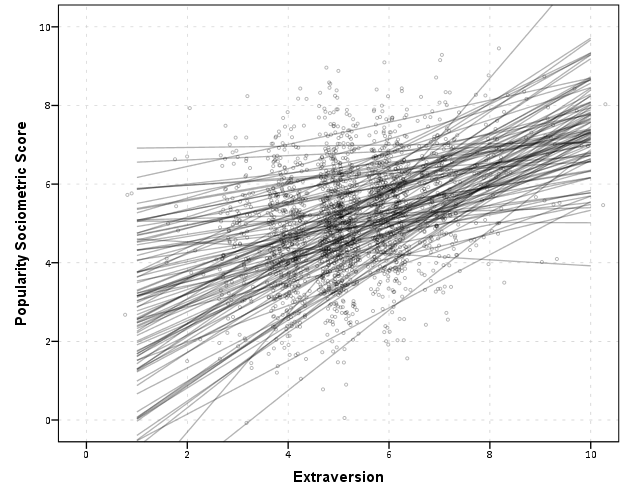

END GPL.Now, we aren’t going to generate this chart. With 100 classes, it will be too difficult to identify any differences between classes unless a whole class is an extreme outlier. Here I am going to make several changes to generate the linear regression line of extraversion on popular within each class. To do this we will make some edits to the ELEMENT statement:

- replace

pointwithline - replace

position(extrav*popular)withposition(smooth.linear(extrav*popular))– this tells SPSS to generate the linear regression line - replace

color.exterior(class)withsplit(class)– the split modifier tells SPSS to generate the regression lines within each class. - make the regression lines semi-transparent by adding in

transparency(transparency."0.7")

Extra things I did for aesthetics:

- I added jittered points to the plot, and made them small and highly transparent (these really aren’t necessary in the plot and are slightly distracting). Note I placed the points first in the GPL code, so the regression lines are drawn on top of the points.

- I changed the

FORMATSofextravandpopulartoF2.0. SPSS takes the formats for the axis in the charts from the original variables, so this prevents decimal places in the chart (and SPSS intelligently chooses to only label the axes at integer values on its own). - I take out the

GUIDE: legendline – it is unneeded since we do not use any colors in the chart. - I change the x and y axis labels, e.g.

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Extraversion"))to be title case.

*Updated chart with smooth regression lines.

FORMATS extrav popular (F2.0).

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=extrav popular class[LEVEL=NOMINAL] MISSING=LISTWISE

REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: extrav=col(source(s), name("extrav"))

DATA: popular=col(source(s), name("popular"))

DATA: class=col(source(s), name("class"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Extraversion"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Popularity Sociometric Score"))

ELEMENT: point.jitter(position(extrav*popular), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.7"), size(size."3"))

ELEMENT: line(position(smooth.linear(extrav*popular)), split(class), transparency(transparency."0.7"))

END GPL.

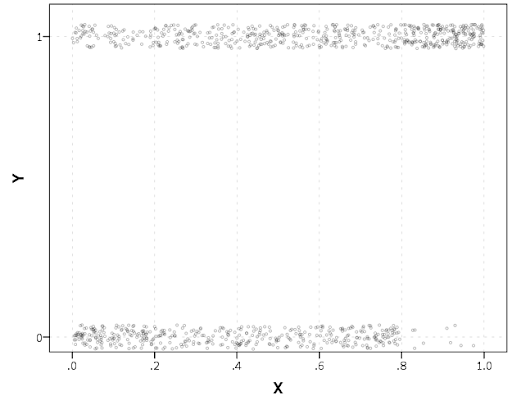

So here we can see that the slopes are mostly positive and have intercepts varying mostly between 0 and 6. The slopes are generally positive and (I would guess) around 0.25. There are a few outlier slopes, and given the class sizes do not vary much (most are around 20) we might dig into these outlier locations a bit more to see what is going on. Generally though with 100 classes it doesn’t strike me as very odd as some going against the norm, and a random effects model with varying intercepts and slopes seems reasonable, as well as the assumption that the distribution of slopes are normal. The intercept and slopes probably have a slight negative correlation, but not as much as I would have guessed with a set of scores that are so restricted in this circumstance.

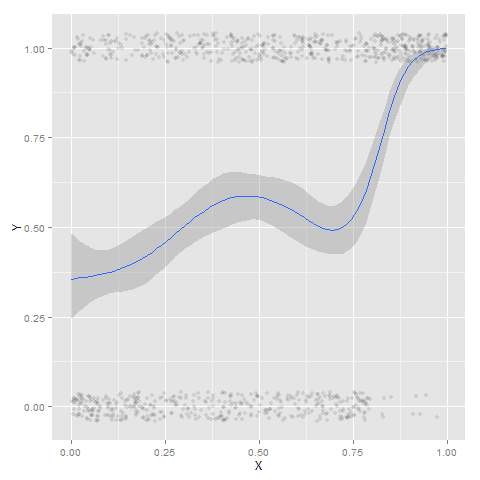

Now the Bell paper has several examples of using the same type of regression lines within groups, but using loess regression estimates to assess non-linearity. This is really simple to update the above plot to incorporate this. One would simply change smooth.linear to smooth.loess. Also SPSS has the ability to estimate quadratic and cubic polynomial terms right within GPL (e.g. smooth.cubic).

Here I will suggest a slightly different chart that allows one to assess how much the linear and non-linear regression lines differ within each class. Instead of super-imposing all of the lines on one plot, I make a small multiple plot where each class gets its own panel. This allows much simpler assessment if any one class shows a clear non-linear trend.

- Because we have 100 groups I make the plot bigger using the

PAGEcommand. I make it about as big as can fit on my screen without having to scroll, and make it 1,200^2 pixels. (Also note when you use aPAGE: begincommand you need an accompanyingPAGE: end()command. - For the small multiples, I wrap the panels by setting

COORD: rect(dim(1,2), wrap()). - I strip the x and y axis labels from the plot (simply delete the

labeloptions within theGUIDEstatements. Space is precious – I don’t want it to be taken up with axis labels and legends. - For the panel label I place the label on top of the panel by setting the opposite option,

GUIDE: axis(dim(3), opposite()).

WordPress in the blog post shrinks the graph to fit on the website, but if you open the graph up in a second window you can see how big it is and explore it easier.

*Checking for non-linear trends.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=extrav popular class[LEVEL=NOMINAL] MISSING=LISTWISE

REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

PAGE: begin(scale(1200px,1200px))

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: extrav=col(source(s), name("extrav"))

DATA: popular=col(source(s), name("popular"))

DATA: class=col(source(s), name("class"), unit.category())

COORD: rect(dim(1,2), wrap())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2))

GUIDE: axis(dim(3), opposite())

ELEMENT: line(position(smooth.linear(extrav*popular*class)), color(color.black))

ELEMENT: line(position(smooth.loess(extrav*popular*class)), color(color.red))

PAGE: end()

END GPL.

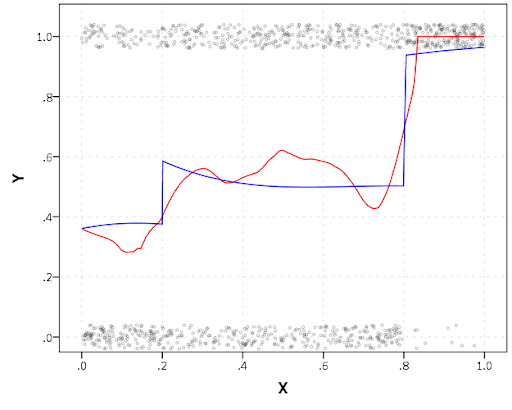

The graph is complicated, but with some work one can go group by group to see any deviations from the linear regression line. So here we can see that most of the non-linear loess lines are quite similar to the linear line within each class. The only one that strikes me as noteworthy is class 45.

Here there is not much data within classes (around 20 students), so we have to wary of small samples to be estimating these non-linear regression lines. You could generate errors around the linear and polynomial regression lines within GPL, but here I do not do that as it adds a bit of complexity to the plot. But, this is an excellent tool if you have many points within your groups and it can be amenable to quite a large set of panels.