Andrew Gelman blogged the other day about an example of Odds Ratios being plotted on a linear scale. I have seen this mistake a couple of times, so I figured it would be worth the time to further elaborate on.

Reported odds ratios are almost invariably from the output of a generalized linear regression model (e.g. logistic, poisson). Graphing the associated exponentiated coefficients and their standard errors (or confidence intervals) is certainly a reasonable thing to want to do – but unless someone wants to be misleading they need to be on a log scale. When the coefficients (and the associated intervals) are exponeniated they are no longer symmetric on a linear scale.

To illustrate a few nefarious examples, lets pretend our software spit out a series of regression coefficients. The table shows the original coefficients on the log odds scale, and the subsequent exponentiated coefficients +- 2 Standard Errors.

Est. Point S.E. Exp(Point) Exp(-2*S.E.) Exp(+2*S.E.)

1 -0.7 0.1 0.5 0.4 0.6

2 0.7 0.1 2.0 1.6 2.5

3 0.2 0.1 1.2 1.0 1.5

4 0.1 0.8 1.1 0.2 5.5

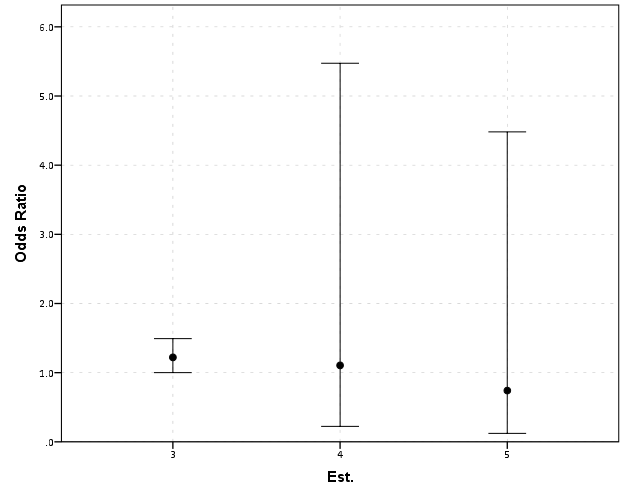

5 -0.3 0.9 0.7 0.1 4.5Now, to start lets graph the exponentiated estimates (the odds ratios) for estimates 1 and 2 and their standard errors on an arithmetic scale, and see what happens.

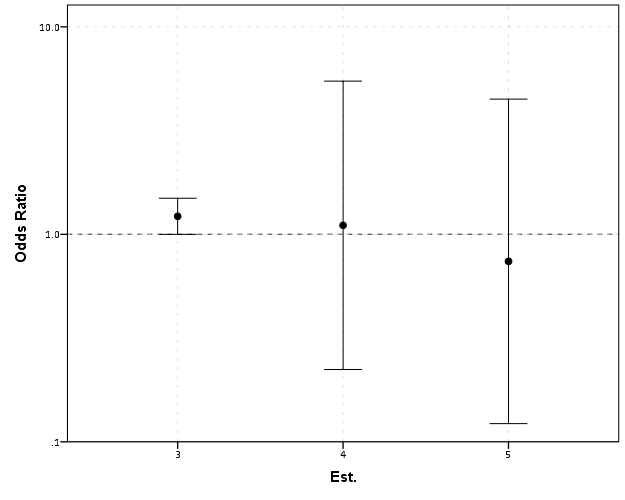

This graph would give the impression that 2 is both a larger effect and has a wider variance than effect 1. Now lets look at the same chart on a log scale.

By construction effects 1 and 2 are exactly the same (this is clear on the original log odds scale before the coefficients were exponentiated). Changes in the ratio of the odds can not go below zero, and a change from an odds ratio between 0.5 and 0.4 is the same relative change as that between 2.0 and 2.5. On the linear scale though the former is a difference of 0.1, and the latter a difference of 0.5.

Such visual discrepancies get larger the further towards zero you go, and as what goes in the denominator and what goes in the numerator is arbitrary, displaying these values on a linear scale is very misleading. Consider a different example:

Well, what would we gather from this? Estimates 4 and 5 both have a wide variance, and the majority of their error bars are both above 1. This is an incorrect interpretation though, as the point estimate of 5 is below 1, and more of its error bar is on the below 1 side.

Looking up some more examples online this may be a problem more often than I thought (doing a google image search for “plot odds ratios” turns up plenty of examples to support my position). I even see some examples of forest plots of odds ratios fail to do this. An oft critique of log scales is that they are harder to understand. Even if I acquiesce that this is true, plotting odds ratios on a linear scale is misleading and should never be done.

To make a set of charts in SPSS with log scales for your particular data you can simply enter in the model estimates using DATA LIST and then use GGRAPH to make the plot. In particular for GGRAPH see the SCALE lines to set the base of the logarithms. Example below:

*Can input your own data.

DATA LIST FREE / Id (A10) PointEst SEPoint Exp_Point CIExp_L CIExp_H.

BEGIN DATA

1 -0.7 0.1 0.5 0.4 0.6

2 0.7 0.1 2.0 1.6 2.5

3 0.2 0.1 1.2 1.0 1.5

4 0.1 0.8 1.1 0.2 5.5

5 -0.3 0.9 0.7 0.1 4.5

END DATA.

DATASET NAME OddsRat.

*Graph of Confidence intervals on log scale.

FORMATS Exp_Point CIExp_L CIExp_H (F2.1).

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=Id Exp_Point CIExp_L CIExp_H

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: Id=col(source(s), name("Id"), unit.category())

DATA: Exp_Point=col(source(s), name("Exp_Point"))

DATA: CIExp_L=col(source(s), name("CIExp_L"))

DATA: CIExp_H=col(source(s), name("CIExp_H"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Point Estimate and 95% Confidence Interval"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2))

GUIDE: form.line(position(1,*), size(size."2"), color(color.darkgrey))

SCALE: log(dim(1), base(2), min(0.1), max(6))

ELEMENT: edge(position((CIExp_L+CIExp_H)*Id))

ELEMENT: point(position(Exp_Point*Id), color.interior(color.black),

color.exterior(color.white))

END GPL.