Motivated by visualizing overlapping intervals from the This is not Rocket Science blog (by Valentine Svensson) (updated link here) I developed some code in SPSS to accomplish a similar feat. Here is an example plot from the blog:

It is related to a graph I attempted to make for visualizing overlap in crime events and interval censored crime data is applicable. The algorithm I mimic by Valentine here is not quite the same, but similar in effect. Here is the macro I made to accomplish this in SPSS. (I know I could also use the python code by the linked author directly in SPSS.)

DEFINE !StackInt (!POSITIONAL = !TOKENS(1)

/!POSITIONAL = !TOKENS(1)

/Fuzz = !DEFAULT("0") !TOKENS(1)

/Out = !DEFAULT(Y) !TOKENS(1)

/Sort = !DEFAULT(Y) !TOKENS(1)

/TempVals = !DEFAULT(100) !TOKENS(1) )

!IF (!Sort = "Y") !THEN

SORT CASES BY !1 !2.

!IFEND

VECTOR #TailEnd(!TempVals).

DO IF ($casenum = 1).

COMPUTE #TailEnd(1) = End + !UNQUOTE(!Fuzz).

COMPUTE !Out = 1.

LOOP #i = 2 TO !TempVals.

COMPUTE #TailEnd(#i) = Begin-1.

END LOOP.

ELSE.

DO REPEAT i = 1 TO !TempVals /T = #TailEnd1 TO !CONCAT("#TailEnd",!TempVals).

COMPUTE T = LAG(T).

DO IF (Begin > T AND MISSING(Y)).

COMPUTE T = End + !UNQUOTE(!Fuzz).

COMPUTE !Out = i.

END IF.

END REPEAT.

END IF.

FORMATS !Out !CONCAT("(F",!LENGTH(!TempVals),".0)").

FREQ !Out /FORMAT = NOTABLE /STATISTICS = MAX.

!ENDDEFINE.An annoyance for this is that I need to place the ending bins in a preallocated vector. Since you won’t know how large the offset values are to begin with, I default to 100 values. The function prints a set of frequencies after the command though (which forces a data pass) and if you have missing data in the output you need to increase the size of the vector.

One simple addition I made to the code over the original is what I call Fuzz in the code above. What happens for crime data is that there are likely to be many near overlaps in addition to many crimes that have an exact known time. What the fuzz factor does is displaces the lines if they touch within the fuzz factor. E.g. if you had two intervals, (1,3) and (3.5,5), if you specified a fuzz factor of 1 the second interval would be placed on top of the first, even though they don’t exactly overlap. This appears to work reasonably well for both small and large n in some experimentation, but if you use too large a fuzz factor it will produce river like runs through the overlap histogram.

Here is an example of using the macro with some fake data.

SET SEED 10.

INPUT PROGRAM.

LOOP #i = 1 TO 1000.

COMPUTE Begin = RV.NORMAL(50,15).

COMPUTE End = Begin + EXP(RV.GAMMA(1,2)).

END CASE.

END LOOP.

END FILE.

END INPUT PROGRAM.

!StackInt Begin End Fuzz = "1" TempVals = 101.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=Begin End Mid

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: End=col(source(s), name("End"))

DATA: Begin=col(source(s), name("Begin"))

DATA: Y=col(source(s), name("Y"), unit.category())

GUIDE: axis(dim(1))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), null())

ELEMENT: edge(position((End+Begin)*Y))

END GPL.And here is the graph:

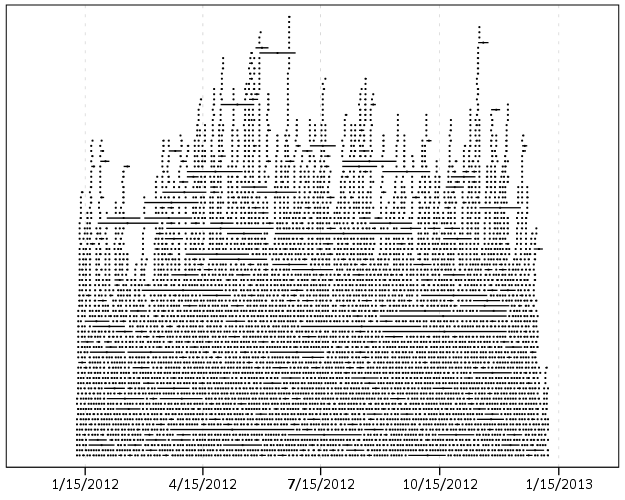

Using the same burglary data from Arlington I used for my aoristic macro, here is an example plot for a few over 6,300 burglaries in Arlington in 2012 using a fuzz factor of 2 days.

This is somewhat misleading, as events with a known exact time are not given any area in the plot. Here is the same plot but with plotting the midpoint of the line as a circle over top of the edge.

You can also add in other information to the plot. Here I color edges and points according to the beat that they are in.

It produces a pretty plot, but it is difficult to discern any patterns. I imagine this plot would be good to evaluate when there is the most uncertainty in crime reports. I might guess if I did this type of plot with burglaries after college students come back from break you may see a larger number of long intervals, showing that they have large times of uncertainty. It is difficult to see any patterns in the Arlington data though besides more events in the summertime (which an aoristic chart would have shown to begin with.) At the level of abstraction of over a year I don’t think you will be able to spot any patterns (like with certain days of the week or times of the month).

I wonder if this would be useful for survival analysis, in particular to spot any temporal or cohort effects.