This is just a quick post on some random graphing examples you can do with SPSS through inline GPL statements, but are not possible through the GUI dialog. These also take knowing alittle bit about the grammar of graphics, and the nuts and bolts of SPSS’s implementation. First up, shading under a curve.

Shading under a curve

I assume the motivation for doing this is obvious, but it is alittle advanced GPL to figure out how to accomplish. I swore someone asked how to do this the other day on NABBLE, but I could not find any such questions. Below is an example.

*****************************************.

input program.

loop #i = 1 to 2000.

compute X = (#i - 1000)/250.

compute PDF = PDF.NORMAL(X,0,1).

compute CDF = CDF.NORMAL(X,0,1).

end case.

end loop.

end file.

end input program.

dataset name sim.

exe.

formats PDF X (F2.1).

*area under entire curve.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=X PDF MISSING=LISTWISE

REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: X=col(source(s), name("X"))

DATA: PDF=col(source(s), name("PDF"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("X"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Prob. Dens."))

ELEMENT: area(position(X*PDF), missing.wings())

END GPL.

*Mark off different areas.

compute tails = 0.

if CDF <= .025 tails = 1.

if CDF >= .975 tails = 2.

exe.

*Area with particular locations highlighted.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=X PDF tails

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: X=col(source(s), name("X"))

DATA: PDF=col(source(s), name("PDF"))

DATA: tails=col(source(s), name("tails"), unit.category())

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), map(("0",color.white),("1",color.grey),("2",color.grey)))

SCALE: cat(aesthetic(aesthetic.transparency.interior), map(("0",transparency."1"),("1",transparency."0"),("2",transparency."0")))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("X"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Prob. Dens."))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), null())

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.transparency.interior), null())

ELEMENT: area(position(X*PDF), color.interior(tails), transparency.interior(tails))

END GPL.

*****************************************.

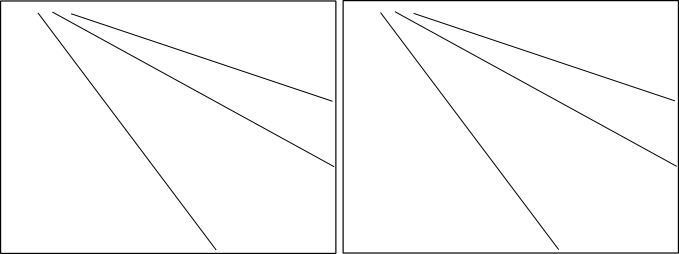

The area under the entire curve is pretty simple code, and can be accomplished through the GUI. The shading under different sections though requires a bit more thought. If you want both the upper and lower tails colored of the PDF, you need to specify seperate categories for them, otherwise they will connect at the bottom of the graph. Then you need to map the categories to specific colors, and if you want to be able to see the gridlines behind the central area you need to make the center area transparent. Note I also omit the legend, as I assume it will be obvious what the graph represents given other context or textual summaries.

Binning scale axis to produce dodging

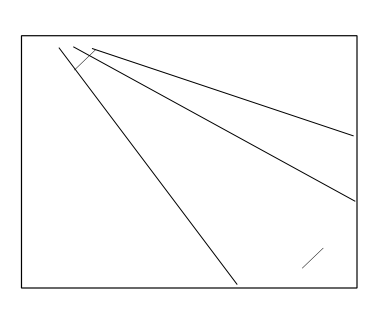

The second example is based on the fact that for SPSS to utilize the dodge collision modifier, one needs a categorical axis. What if you want the axis to really be scale though? You can make the data categorical but the axis on a continuous scale by specifying a binned scale, but just make the binning small enough to suit your actual data values. This is easy to show with a categorical dot plot. If you can, IMO it is better to use dodging than jittering, and below is a perfect example. If you run the first GGRAPH statement, you will see the points aren’t dodged, although the graph is generated just fine and dandy with no error messages. The second graph bins the X variable (which is on the second dimension) with intervals of width 1. This ends up being exactly the same as the continuous axis, because the values are all positive integers anyway.

*****************************************.

set seed = 10.

input program.

loop #i = 1 to 1001.

compute X = TRUNC(RV.UNIFORM(0,101)).

compute cat = TRUNC(RV.UNIFORM(1,4)).

end case.

end loop.

end file.

end input program.

dataset name sim.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=X cat

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: X=col(source(s), name("X"))

DATA: cat=col(source(s), name("cat"), unit.category())

COORD: rect(dim(1,2))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("cat"))

ELEMENT: point.dodge.symmetric(position(cat*X))

END GPL.

*Now lets try to bin X so the points actually dodge!.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=X cat

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: X=col(source(s), name("X"))

DATA: cat=col(source(s), name("cat"), unit.category())

COORD: rect(dim(1,2))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("cat"))

ELEMENT: point.dodge.symmetric(position(bin.rect(cat*X, dim(2), binWidth(1))))

END GPL.

****************************************.

Both examples shown here only take slight alterations to code generatable through the GUI, but take a bit more understanding of the grammar to know how to accomplish (or even know they are possible). You unfortunately can’t implement Wilkinson’s (1999) true dot plot technique like this (he doesn’t suggest binning, but by choosing where the dots are placed by KDE estimation). But this should be sufficient for most circumstances.