This will be a long one, but I have some notes on synthetic control and the back-and-forth between two groups. So first if you aren’t familiar, Tom Hogan published an article on how the progressive District Attorney (DA) in Philadelphia, Larry Krasner, in which Hogan estimates that Krasner’s time in office contributed to a large increase in the number of homicides. The control homicides are estimated using a statistical technique called synthetic control, in which you derive estimates of the trend in homicides to compare Philly to based on a weighted average of comparison cities.

Kaplan and colleagues (KNS from here on) then published a critique of various methods Hogan used to come up with his estimate. KNS provided estimates using different data and a different method to derive the weights, showing that Philadelphia did not have increased homicides post Krasner being elected. For reference:

Part of the reason I am writing this is if people care enough, you could probably make similar back and forths on every synth paper. There are many researcher degrees of freedom in the process, and in turn you can make reasonable choices that lead to different results.

I think it is worthwhile digging into those in more detail though. For a summary of the method notes I discuss for this particular back and forth:

- Researchers determine the treatment estimate they want (counts vs rates) – solvers misbehaving is not a reason to change your treatment effect of interest

- The default synth estimator when matching on counts and pop can have some likely unintended side-effects (NYC pretty much has to be one of the donor cities in this dataset)

- Covariate balancing is probably a red-herring (so the data issues Hogan critiques in response to KNS are mostly immaterial)

In my original draft I had a note that this post would not be in favor of Hogan nor KNS, but in reviewing the sources more closely, nothing I say here conflicts with KNS (and I will bring a few more critiques of Hogan’s estimates that KNS do not mention). So I can’t argue much with KNS’s headline that Hogan’s estimates are fatally flawed.

An overview of synthetic control estimates

To back up and give an overview of what synth is for general readers, imagine we have a hypothetical city A with homicide counts 10 15 30, where the 30 is after a new DA has been elected. Is the 30 more homicides than you would have expected absent that new DA? To answer this, we need to estimate a counterfactual trend – what the homicide count would have been in a hypothetical world in which a new progressive DA was not elected. You can see the city homicides increased the prior two years, from 10 to 15, so you may say “ok, I expected it to continue to increase at the same linear trend”, in which case you would have expected it to increase to 20. So the counterfactual estimated increase in that scenario is observed - counterfactual, here 30 - 20 = 10, an estimated increase of 10 homicides that can be causally attributed to the progressive DA.

Social scientists tend to not prefer to just extrapolate prior trends from the same location into the future. There could be widespread changes that occur everywhere that caused the increase in city A. If homicide rates accelerated in every city in the country, even those without a new progressive DA, it is likely something else is causing those increases. So say we compare city A to city B, and city B had a homicide count trend during the same time period 10 15 35. Before the new DA in city A, cities A/B had the same pre-trend (both 10 15). The post time period City B increased to 35 homicides. So if using City B as the counterfactual estimate, we have the progressive DA reduced 5 homicides, again observed - counterfactual = 30 - 35 = -5. So even though city A increased, it increased less than we expected based on the comparison city B.

Note that this is not a hypothetical concern, it is pretty basic one that you should always be concerned about when examining macro level crime data. There has been national level homicide increases over the time period when Krasner has been in office (Yim et al, 2020, and see this blog post for updates. U.S. city homicide rates tend to be very correlated with each other (McDowall & Loftin, 2009).

So even though Philly has increased in homicide counts/rates when Krasner has been in office, the question is are those increases higher or lower than we would expect. That is where the synthetic control method comes in, we don’t have a perfect city B to compare to Philadelphia, so we create our own “synthetic” counter-factual, based on a weighted average of many different comparison cities.

To make the example simple, imagine we have two potential control cities and homicide trends, city C1 0 30 20, and city C2 20 0 30. Neither looks like a good comparison to city A that has trends 10 15 30. But if we do a weighted average of C1 and C2, with the weights 0.5 for each city, when combined they are a perfect match for the two pre-treatment periods:

C0 C1 Average cityA

0 20 10 10

30 0 15 15

20 30 25 30

This is what the synthetic control estimator does, although instead of giving equal weights it determines the optimal weights to match the pre-treatment time period given many potential donors. In real data for example C0 and C1 may be given weights of 0.2 and 0.8 to give the correct balance based on the prior to treatment time periods.

The fundamental problem with synth

The rub with estimating the synth weights is that there is no one correct way to estimate the weights – you have more numbers to estimate than data points. In the Hogan paper, he has 5 pre time periods, 2010-2014, and he has 82 potential donors (99 other of the largest cities in the US minus 17 progressive prosecutors). So you need to learn 82 numbers (the weights) based on 5 data points.

Side note: you can also consider matching on covariates additional data points, although I will go into more detail on how matching on covariates is potentially a red-herring. Hogan I think uses an additional 5*3=15 time varying points (pop, cleared homicide, homicide clearance rates), and maybe 3 additional time invariant (median income, 1 prosecutor categorization, and homicides again!). So maybe has 5 + 15 + 3 = 23 data points to match on (so same fundamental problem, 23 numbers to learn 82 weights). I am just going to quote the full passage on Hogan (2022a) here where he discusses covariate matching:

The number of homicides per year is the dependent variable. The challenge with this synthetic control model is to use variables that both produce parallel trends in the pre-period and are sufficiently robust to power the post-period results. The model that ultimately delivered the best fit for the data has population, cleared homicide cases, and homicide clearance rates as regular predictors. Median household income is passed in as the first special predictor. The categorization of the prosecutors and the number of homicides are used as additional special predictors. For homicides, the raw values are passed into the model. Abadie (2021) notes that the underlying permutation distribution is designed to work with raw data; using log values, rates, or other scaling techniques may invalidate results.

This is the reason why replication code is necessary – it is very difficult for me to translate this to what Hogan actually did. “Special” predictors here are code words for the R synth package for time-invariant predictors. (I don’t know based on verbal descriptions how Hogan used time-invariant for the prosecutor categorization for example, just treats it as a dummy variable?) Also only using median income – was this the only covariate, or did he do a bunch of models and choose the one with the “best” fit (it seems maybe he did do a search, but doesn’t describe the search, only the end selected result).

I don’t know what Hogan did or did not do to fit his models. The solution isn’t to have people like me and KNS guess or have Hogan just do a better job verbally describing what he did, it is to release the code so it is transparent for everyone to see what he did.

So how do we estimate those 82 weights? Well, we typically have restrictions on the potential weights – such as the weights need to be positive numbers, and the weights should sum to 1. These are for a mix of technical and theoretical reasons (having the weights not be too large can reduce the variance of the estimator is a technical reason, we don’t want negative weights as we don’t think there are bizzaro comparison areas that have opposite world trends is a theoretical one).

These are reasonable but ultimately arbitrary – there are many different ways to accomplish this weight estimation. Hogan (2022a) uses the R synth package, KNS use a newer method also advocated by Abadie & L’Hour (2021) (very similar, but tries to match to the closest single city, instead of weights for multiple cities). Abadie (2021) lists probably over a dozen different procedures researchers have suggested over the past decade to estimate the synth weights.

The reason I bring this up is because when you have a problem with 82 parameters and 5 data points, the problem isn’t “what estimator provides good fit to in-sample data” – you should be able to figure out a estimator that accomplishes good in-sample fit. The issue is whether that estimator is any good out-of-sample.

Rates vs Counts

So besides the estimator used, you can break down 3 different arbitrary researcher data decisions that likely impact the final inferences:

- outcome variable (homicide counts vs homicide per capita rates)

- pre-intervention time periods (Hogan uses 2010-2014, KNS go back to 2000)

- covariates used to match on

Lets start with the outcome variable question, counts vs rates. So first, as quoted above, Hogan cites Abadie (2021) for saying you should prefer counts to rates, “Abadie (2021) notes that the underlying permutation distribution is designed to work with raw data; using log values, rates, or other scaling techniques may invalidate results.”

This has it backwards though – the researcher chooses whether it makes sense to estimate treatment effects on the count scale vs rates. You don’t goal switch your outcome because you think the computer can’t give you a good estimate for one outcome. So imagine I show you a single city over time:

Y0 Y1 Y2

Count 10 15 20

Pop 1000 1500 2000

You can see although the counts are increasing, the rate is consistent over the time period. There are times I think counts make more sense than rates (such as cost-benefit analysis), but probably in this scenario the researcher would want to look at rates (as the shifting denominator is a simple explanation causing the increase in the counts).

Hogan (2022b) is correct in saying that the population is not shifting over time in Philly very much, but this isn’t a reason to prefer counts. It suggests the estimator should not make a difference when using counts vs rates, which just points to the problematic findings in KNS (that making different decisions results in different inferences).

Now onto the point that Abadie (2021) says using rates is wrong for the permutation distribution – I don’t understand what Hogan is talking about here. You can read Abadie (2021) for yourself if you want. I don’t see anything about the permutation inferences and rates.

So maybe Hogan mis-cited and meant another Abadie paper – Abadie himself uses rates for various projects (he uses per-capita rates in the 2021 cited paper, Abadie et al., (2010) uses rates for another example), so I don’t think Abadie thinks rates are intrinsically problematic! Let me know if there is some other paper I am unaware of. I honestly can’t steelman any reasonable source where Hogan (2022a) came up with the idea that counts are good and rates are bad though.

Again, even if they were, it is not a reason to prefer counts vs rates, you would change your estimator to give you the treatment effect estimate you wanted.

Side note: Where I thought the idea with the problem with rates was going (before digging in and not finding any Abadie work actually saying there is issues with rates), was increased variance estimates with homicide data. So Hogan (2022a) estimates for the synth weights Detroit (0.468), New Orleans (NO) (0.334), and New York City (NYC) (0.198), here are those cities homicide rates graphed (spreadsheet with data + notes on sources).

You can see NO’s rate is very volatile, so is not a great choice for a matched estimator if using rates. (I have NO as an example in Wheeler & Kovandzic (2018), that much variance though is fairly normal for high crime not too large cities in the US, see Baltimore for example for even more volatility.) I could forsee someone wanting to make a weighted synth estimator for rates, either make the estimator a population weighted average, or penalize the variance for small rates. Maybe you can trick microsynth to do a pop weighted average out of the box (Robbins et al., 2017).

To discuss the Hogan results specifically, I suspect for example NYC being a control city with high weight in the Hogan paper, which superficially may seem good (both large cities on the east coast), actually isn’t a very good control area considering the differences in homicide trends (either rates or counts) over time. (I am also not so sure about describing NYC and New Orlean’s as “post-industrial” by Hogan (2022a) either. I mean this is true to the extent that all urban areas in the US are basically post-industrial, but they are not rust belt cities like Detroit.)

Here is for reference counts of homicides in Philly, Detroit, New Orleans, and NYC going back further in time:

NYC is such a crazy drop in the 90s, lets use the post 2000 data that KNS used to zoom in on the graph.

I think KNS are reasonable here to use 2000 as a cut point – it is more empirical based (post crime drop), in which you could argue the 90’s are a “structural break”, and that homicides settled down in most cities around 2000 (but still typically had a gradual decline). Given the strong national homicide trends though across cities (here is an example I use for class, superimposing Dallas/NYC/Chicago), I think using even back to the 60’s is easily defensible (moreso than limiting to post 2010).

It depends on how strict you want to be whether you consider these 3 cities “good” matches for the counts post 2010 in Hogan’s data. Detroit seems a good match on the levels and ok match on trends. NO is ok match on trends. NYC and NO balance each other in terms of matching levels, NYC has steeper declines though (even during the 2010-2014 period).

The last graph though shows where the estimated increases from Hogan (2022a) come from. Philly went up and those 3 other cities went down from 2015-2018 (and had small upward bumps in 2019).

Final point in this section, careful what you wish for with sparse weights and sum to 1 in the synth estimate. What this means in practice when using counts and matching on pop size, is that you need lines that are above and below Philly on those dimensions. So to get a good match on Pop, it needs to select at least one of NYC/LA/Houston (Chicago was eliminated due to having a progressive prosecutor). To get a good match on homicide counts, it also has to pick at least one city with more homicides per year as well, which limits the options to New York and Detroit (LA/Houston have lower overall homicide counts to Philly).

You can’t do the default Abadie approach for NYC for example (matching on counts and pop) – it will always have a bad fit when using comparison cities in the US as the donor pool. You either need to allow the weights to sum to larger than 1, or the lasso approach with an intercept is another option (so you only match on trend, not levels).

Because matching on trends is what matters for proper identification in this design, not levels, this is all sorts of problematic with the data at hand. (This is also a potential problem with the KNS estimator as well. KNS note though they don’t trust their estimate offhand, their reasonable point is that small changes in the design result in totally different inferences.)

Covariates and Out of Sample Estimates

For sake of argument, say I said Hogan (2022a) is bunk, because it did not match on “per-capita annual number of cheese-steaks consumed”. Even though on its face this covariate is non-sense, how do you know it is non-sense? In the synthetic control approach, there is no empirical, falsifiable way to know whether an covariate is a correct one to match on. There is no way to know that median income is better than cheese-steaks.

If you wish for more relevant examples, Philly has obviously more issues with street consumption of opioids than Detroit/NOLA/NYC, which others have shown relationships to homicide and has been getting worse over the time Krasner has been in office (Rosenfeld et al., 2023). (Or more simply social disorganization is the more common way that criminologists think about demographic trends and crime.)

This uncertainty in “what demographics to control for” is ok though, because matching on covariates is neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure you have estimated a good counter-factual trend. Abadie in his writings intended for covariates to be more like fuzzy guide-rails – they are qualitative things that you think the comparison areas should be similar on.

Because there are effectively an infinite pool of potential covariates to match on, I prefer the approach of simply limiting the donor pool apriori – Hogan limiting to large cities is on its face reasonable. Including other covariates is not necessary, and does not make the synth estimate more or less robust. Whether KNS used good or bad data for covariates is entirely a red-herring as to the quality of the final synth estimate.

Side note: I don’t doubt that Hogan got advice to not share data and code. It is certainly not normative in criminology to do this. It creates a bizarre situation though, in which someone can try to replicate Hogan by collating original sources, and then Hogan always comes back and says “no, the data you have are wrong” or “the approach you did is not exactly replicating my work”.

I get that collating data takes a long time, and people want to protect their ability to publish in the future. (Or maybe just limit their exposure to their work being criticized.) It is blatantly antithetical to verifying the scientific integrity of peoples work though.

Even if Hogan is correct though in the covariates that KNS used are wrong, it is mostly immaterial to the quality of the synth estimates. It is a waste of time for outside researchers to even bother to replicate Hogan’s covariates he used.

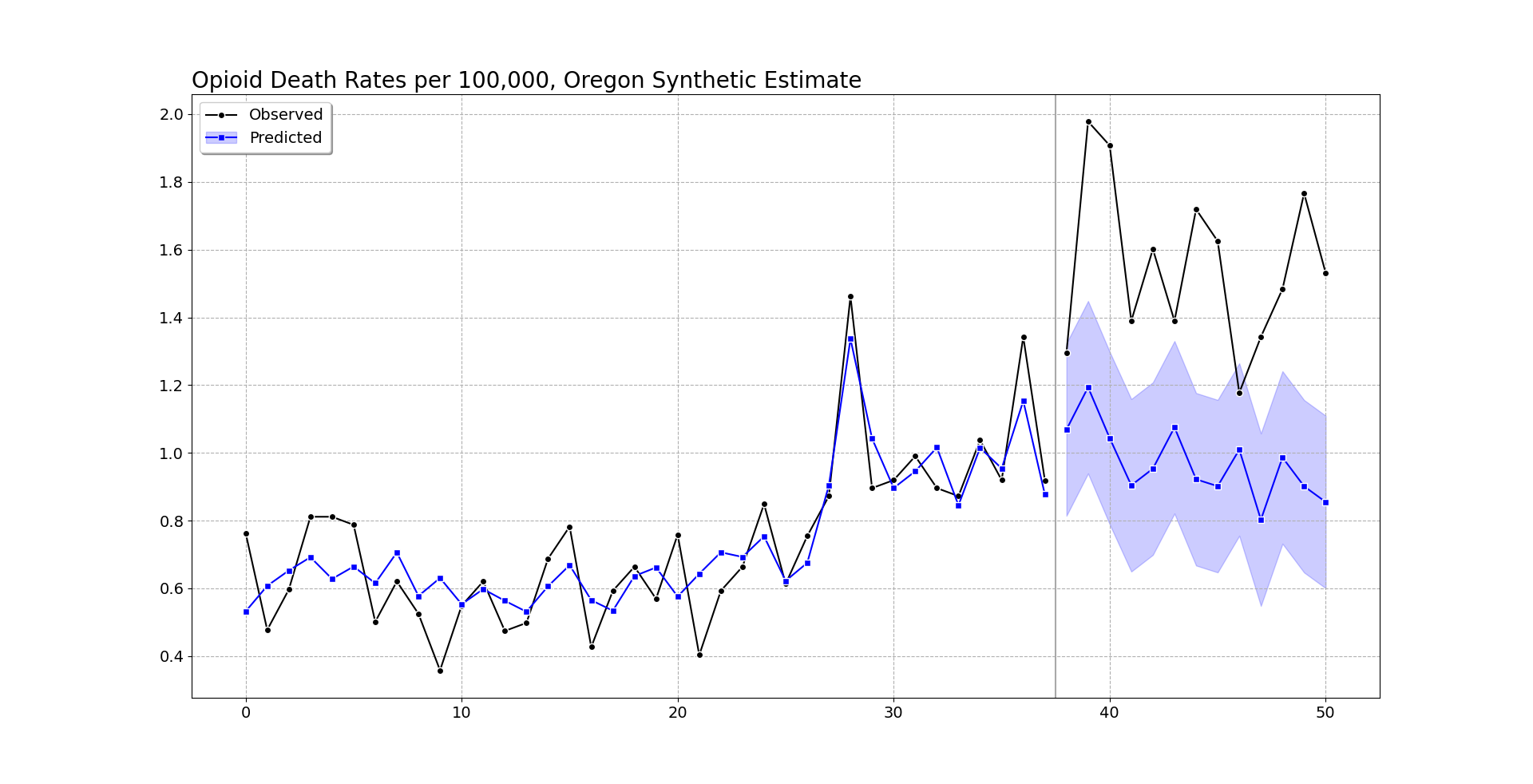

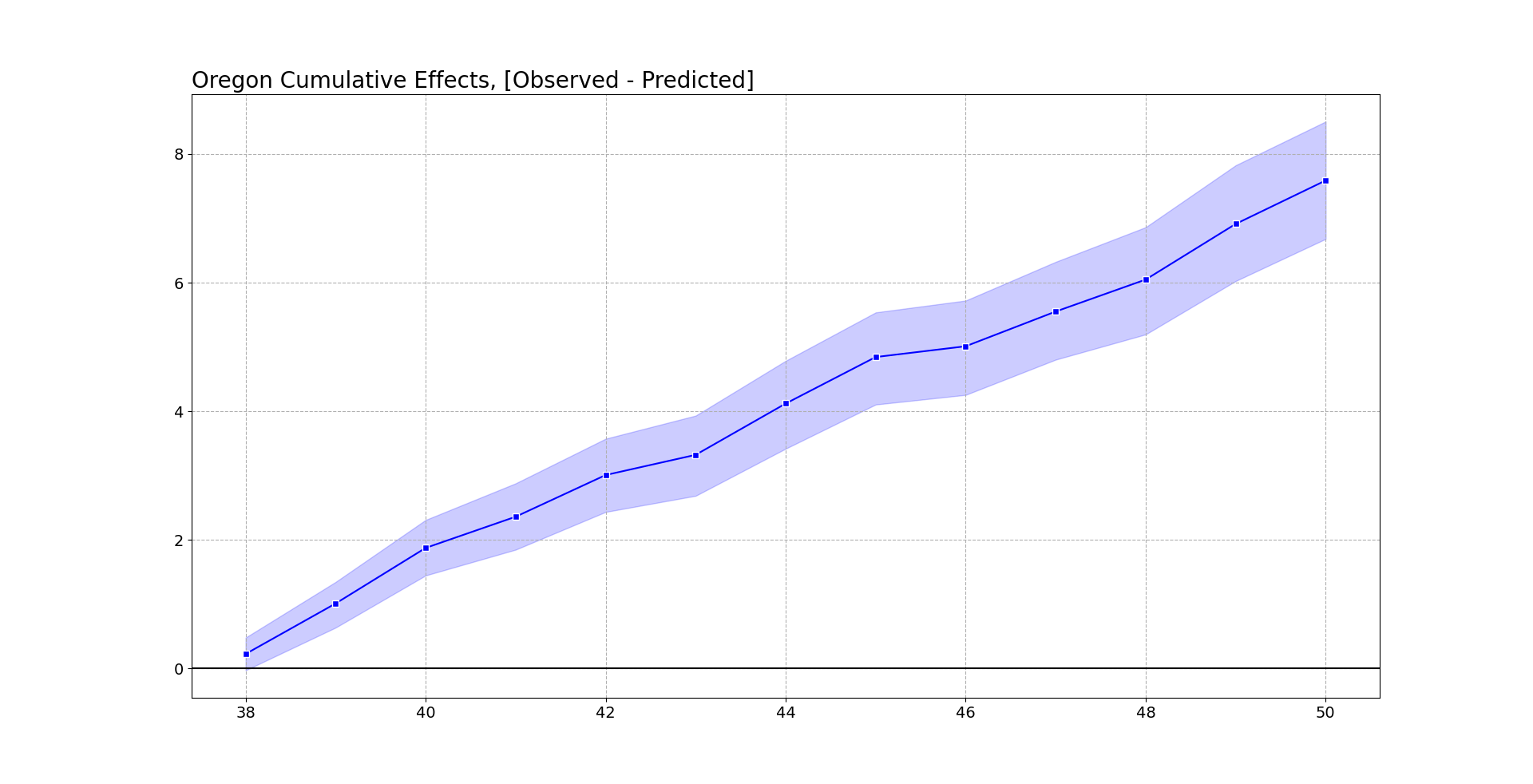

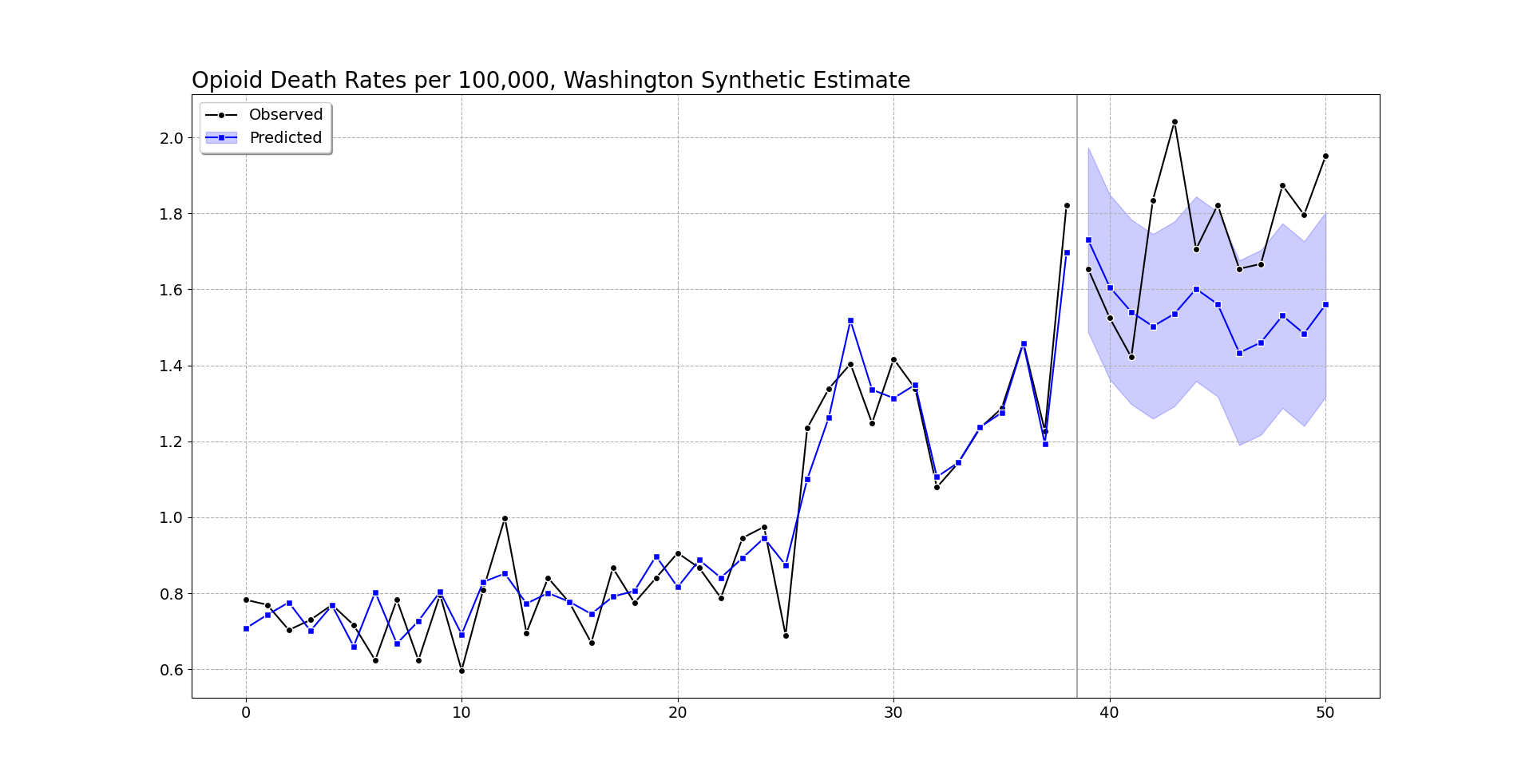

So I used the idea of empirical/falsifiable – can anything associated with synth be falsifiable? Why yes it can – the typical approach is to do some type of leave-one-out estimate. It may seem odd because synth estimates an underlying match to a temporal trend in the treated location, but there is nothing temporal about the synth estimate. You could jumble up the years in the pre-treatment sample and still would estimate the same weights.

Because of this, you can leave-a-year-out in the pre-treatment time period, run your synth algorithm, and then predict that left out year. A good synth estimator will be close to the observed value for the out of sample estimates in the pre-treated time period (and as a side bonus, you can use that variance estimate to estimate the error in the post-trend years).

That is a relatively simple way to determine if the Hogan 5 year vs KNS 15 year time periods are “better” synth controls (my money is on KNS for that one). Because Hogan has not released data/code, I am not going to go through that trouble. As I said in the side note earlier, I could try to do that, and Hogan could simply come back and say “you didn’t do it right”.

This also would settle the issue of “over-fit”. You actually cannot just look at the synth weights, and say that if they are sparse they are not over-fit and if not sparse are over-fit. So for reference, you have in Hogan essentially fitting 82 weights based on 5 datapoints, and he identified a fit with 3 non-zero weights. Flip this around, and say I had 5 data points and fit a model with 3 parameters, it is easily possible that the 3 parameter model in that scenario is overfit.

Simultaneously, it is not necessary to have a sparse weights matrix. Several alternative methods to estimate synth will not have sparse weights (I am pretty sure Xu (2017) will not have sparse weights, and microsynth estimates are not sparse either for just two examples). Because US cities have such clear national level trends, a good estimator in this scenario may have many tiny weights (where good here is low bias and variance out of sample). Abadie thinks sparse weights are good to make the model more interpretable (and prevent poor extrapolation), but that doesn’t mean by default a not sparse solution is bad.

To be clear, KNS admit that their alternative results are maybe not trustworthy due to not sparse weights, but this doesn’t imply Hogan’s original estimates are themselves “OK”. I think maybe a correct approach with city level homicide rate data will have non-sparse weights, due to the national level homicide trend that is common across many cities.

Wrapping Up

If Crim and Public Policy still did response pieces maybe I would go through that trouble of doing the cross validation and making a different estimator (although I would unlikely be an invited commenter). But wanted to at least do this write up, as like I said at the start I think you could do this type of critique with the majority of synth papers in criminology being published at the moment.

To just give my generic (hopefully practical) advice to future crim work:

- don’t worry about matching on covariates, worry about having a long pre-period

- the default methods you need to worry about if you have enough “comparable” units – this is in terms of levels, not just trends

- the only way to know the quality of the modeling procedure in synth is to do out of sample estimates.

Bullet points 2/3 are perhaps not practical – most criminologists won’t have the capability to modify the optimization procedure to the situation at hand (I spent a few days trying without much luck to do my penalized variants suggested, sharing so others can try out themselves, I need to move onto other projects!) Also takes a bit of custom coding to do the out of sample estimates.

For many realistic situations though, I think criminologists need to go beyond just point and clicking in software, especially for this overdetermined system of equations synthetic control scenario. I did a prior blog post on how I think many state level synth designs are effectively underpowered (and suggested using lasso estimates with conformal intervals). I think that is a better default in this scenario as well compared to the typical synth estimators, although you have plenty of choices.

Again I had initially written this as trying to two side the argument, and not being for or against either set of researchers. But sitting down and really reading all the sources and arguments, KNS are correct in their critique. Hogan is essentially hiding behind not releasing data and code, and in that scenario can make an endless set of (ultimately trivial) responses of anyone who publishes a replication/critique.

Even if some of the the numbers KNS collated are wrong, it does not make Hogan’s estimates right.

References

- Abadie, A. (2021). Using synthetic controls: Feasibility, data requirements, and methodological aspects. Journal of Economic Literature, 59(2), 391-425.

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493-505.

- Abadie, A., & L’hour, J. (2021). A penalized synthetic control estimator for disaggregated data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 116(536), 1817-1834.

- Hogan, T.P. (2022a) De‐prosecution and death: A synthetic control analysis of the impact of de‐prosecution on homicides. Criminology & Public Policy, 21(3), 489-534.

- Hogan, T.P. (2022b) DE-PROSECUTION AND DEATH: A CORDIAL REPLY TO KAPLAN, NADDEO & SCOTT.

- Kaplan, J., Naddeo, J., & Scott, T. (2022) De-prosecution and death: A comment on the fatal flaws in Hogan (2022).

- McDowall, D., & Loftin, C. (2009). Do US city crime rates follow a national trend? The influence of nationwide conditions on local crime patterns. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 307-324.

- Robbins, M. W., Saunders, J., & Kilmer, B. (2017). A framework for synthetic control methods with high-dimensional, micro-level data: evaluating a neighborhood-specific crime intervention. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 112(517), 109-126.

- Rosenfeld, R., Roth, R., & Wallman, J. (2023). Homicide and the opioid epidemic: a longitudinal analysis. Homicide Studies, 27(3), 321-337.

- Wheeler, A. P., & Kovandzic, T. V. (2018). Monitoring volatile homicide trends across US cities. Homicide Studies, 22(2), 119-144.

- Xu, Y. (2017). Generalized synthetic control method: Causal inference with interactive fixed effects models. Political Analysis, 25(1), 57-76.

- Yim, H. N., Riddell, J. R., & Wheeler, A. P. (2020). Is the recent increase in national homicide abnormal? Testing the application of fan charts in monitoring national homicide trends over time. Journal of Criminal Justice, 66, 101656..