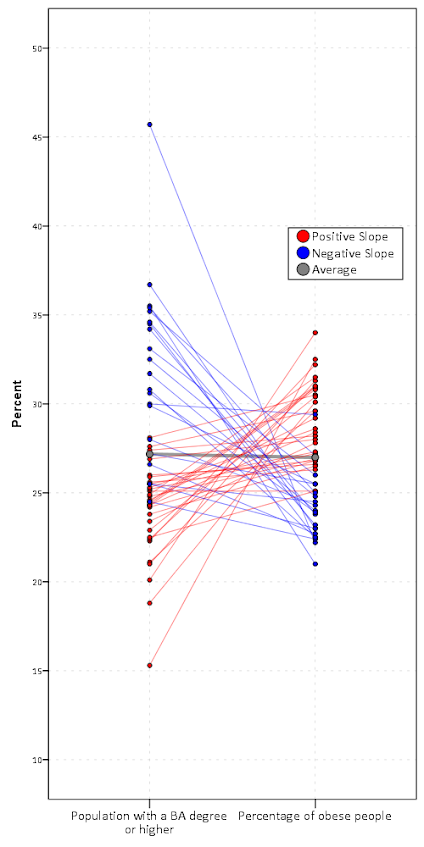

So I was interested in scraping data from the Google Places API recently. My motivation came from some criminology studies that examine the relationship between coffee shops and crime (Papachristos et al. 2011; Smith, 2014) under the auspices that coffee shops are a measure of gentrification. I am also interested in gaining information about other place characteristics as well, as whether a place has some sort of non-residential application (e.g. bus stop, gas station) they tend to have elevated amounts of crime compared to solely residential locations. (These are not per-se characteristics that make places criminogenic – they just influence the walking around population and thus make the baseline exposure of places greater because of more human interaction).

So here I will give an example of grabbing data from the Google Places API given a grid of locations from SPSS and exporting to an SPSS dataset. So first you need sign up for an API key with Google from the Google APIs console. This allows 1,000 queries per day. Here I will make an example of 6 cases, but again with just the base query rates you can submit up to 1,000 requests per day (and can get 100,000 by verifying your identity).

*Need UNICODE. PRESERVE. SET UNICODE=ON. *Some example data. DATA LIST FREE / ID Lat Lng. BEGIN DATA 1 38.901989 -77.041921 2 38.901991 -77.036157 3 38.901993 -77.030393 4 38.906493 -77.041924 5 38.906495 -77.036159 6 38.906497 -77.030394 END DATA. DATASET NAME Locations.

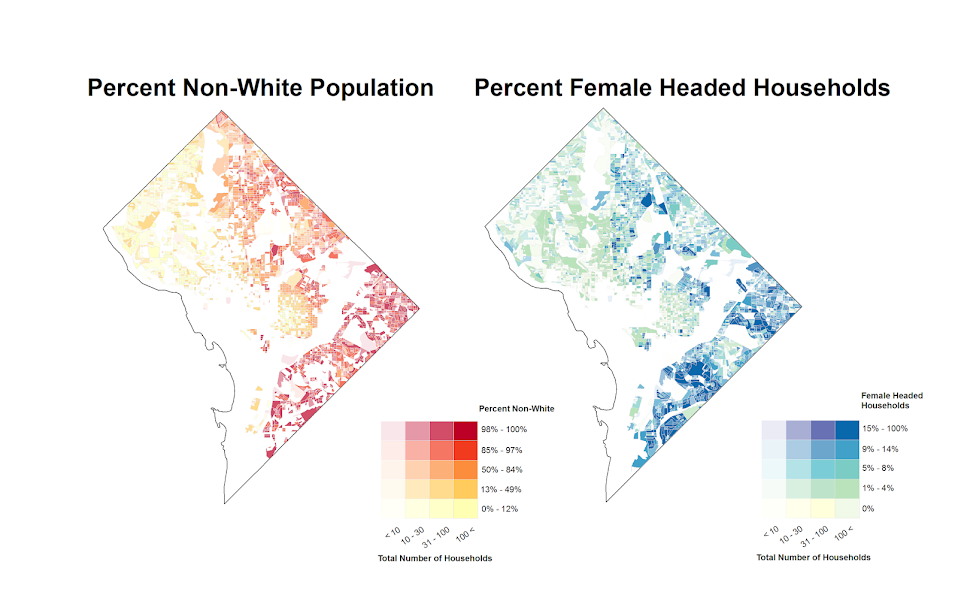

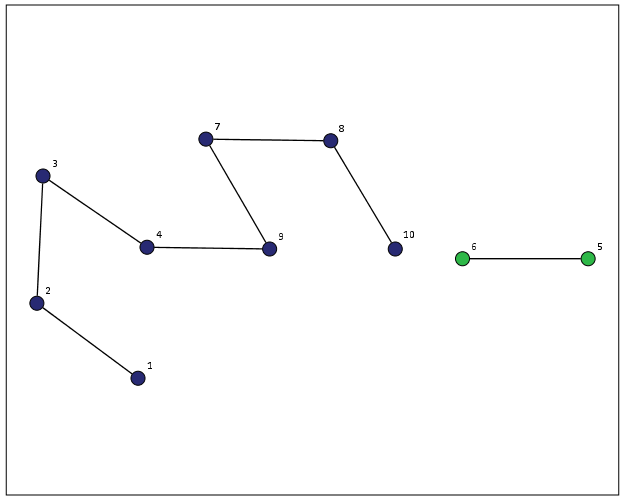

I typically don’t have SPSS in Unicode mode, but since Google will return some results in Unicode it is necessary to turn it on. After that I create a dataset with 6 locations in central D.C. These happen to be centroids from a regular grid I laid over the city with 500 meter square grid cells (and it only takes 800 and some cells to cover the city of D.C.).

Now google has a pretty good intro to get your feet wet, so here I will just show the helper functions I created to ease the task. The first function takes as input parameters latitude, longitude, a radius (in meters), a type field, and your key for the maps API. It then grabs the JSON you get as a response from that specific url, and then turns the JSON object into a nested list that can be traversed in python. You can check out from Google what other information is available, but the IterJson function is just a helper to takes specific results from GoogPlac and put them into a nicer array for me to use. Here I just grab the geographic coordinates, a place name, a reference string, and the address associated with the place.

*Functions to grab the necessary data from Google.

BEGIN PROGRAM.

import urllib, json

#Grabbing and parsing the JSON data

def GoogPlac(lat,lng,radius,types,key):

#making the url

AUTH_KEY = key

LOCATION = str(lat) + "," + str(lng)

RADIUS = radius

TYPES = types

MyUrl = ('https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/place/nearbysearch/json'

'?location=%s'

'&radius=%s'

'&types=%s'

'&sensor=false&key=%s') % (LOCATION, RADIUS, TYPES, AUTH_KEY)

#grabbing the JSON result

response = urllib.urlopen(MyUrl)

jsonRaw = response.read()

jsonData = json.loads(jsonRaw)

return jsonData

#This is a helper to grab the Json data that I want in a list

def IterJson(place):

x = [place['name'], place['reference'], place['geometry']['location']['lat'],

place['geometry']['location']['lng'], place['vicinity']]

return x

END PROGRAM.

Now we can set up the parameters for the search in addition to the geographic coordinates. Here I make python objects specifying the search type cafe and my API key. I will pass a constant for the radius field of 375 meters – which will cause just a bit of overlap among my grid cells.

*Setting the parameters I will use in the query - type & my key. BEGIN PROGRAM. #necessary info for geocoding MyKey = 'Your API Key Here!!!' MyType = 'cafe' END PROGRAM.

Now the magic happens; this code 1) declares a new dataset to place the results in, and then in python 2) grabs the current SPSS dataset, 3) sets the variables for the new dataset, 4) searches at each longitude value in the original dataset, and 5) appends cases to the new SPSS dataset for every location result returned for each initial longitude location. The nested loops are necessary as one location will return multiple places. (For those not using SPSS, the SPSS data here, alldata, is simply a list of namedTuple’s for each row of SPSS data. This code is basically amenable to whatever data structure you are working with, just loop through your grid of geographic coordinates and then append those results to whatever data structure you want.)

*Now querying google and placing the results into a new file.

DATASET DECLARE PlacesResults.

BEGIN PROGRAM.

#Grabbing SPSS data

import spss, spssdata

alldata = spssdata.Spssdata().fetchall()

#making an SPSS dataset to place the results into

spss.StartDataStep()

datasetObj = spss.Dataset(name='PlacesResults')

datasetObj.varlist.append('Id',0)

datasetObj.varlist.append('LatSearch',0)

datasetObj.varlist.append('LngSearch',0)

datasetObj.varlist.append('name',100)

datasetObj.varlist.append('reference',500)

datasetObj.varlist.append('LatRes',0)

datasetObj.varlist.append('LngRes',0)

datasetObj.varlist.append('vicinity',300)

#appending the data to the SPSS dataset

for case in alldata:

search = GoogPlac(lat=case[1],lng=case[2],radius=375,types=MyType,key=MyKey) #grab data

if search['status'] == 'OK': #loop through results

for place in search['results']:

x = IterJson(place)

results = list(case) + x

datasetObj.cases.append(results) #appending data to SPSS dataset

spss.EndDataStep()

END PROGRAM.

Now we have the data in our PlacesResults SPSS dataset for further manipulation or whatever. One of comment on a prior post was basically "What is the point of SPSS, I can do all of this in Python". Well this is generally true – but I continue to do work in SPSS because it is much more convenient a tool for data management then Python (at least for myself, knowing SPSS really well and Python not so well). So here because we have slightly overlapping search radius’s, you will have duplicate results in your set. The following code in SPSS eliminates those duplicate results.

*************************************. *Getting rid of duplicate results. DATASET ACTIVATE PlacesResults. SHOW N. SORT CASES BY name vicinity LatRes LngRes Id. MATCH FILES FILE = * /FIRST = Keep /BY name vicinity LatRes LngRes. SELECT IF Keep = 1. MATCH FILES FILE = * /DROP Keep. EXECUTE. SHOW N. *************************************.

So now you can do the analysis with your results without having to worry about duplicates. If you don’t want to keep SPSS in Unicode mode, remember to restore your settings before you end your SPSS session.

*Restoring back to LOCAL mode. DATASET CLOSE ALL. NEW FILE. RESTORE.

So, I have done all this, but I must admit that it appears to me that this act would violate the terms of service for using the Google Places API data (see 10.1.3 Restrictions against Data Export or Copying specifically), as this is creating a database of the cached results. But others like FloatingSheep do approximately the same type of requests (and obviously cache the data in a permanent database to make such maps). Maybe if someone from Google is listening they can let me know if I am violating the terms of service for doing such a non-commercial academic project.

I will update at a later point about the results of the cafes and crime at the micro place level in DC (as part of my dissertation). There actually is a set of sidewalk cafe’s From DC.gov and a quick look with one of the older files I have (downloaded in Oct-13) there are 452 listed cafes. The scraped data from google only totals 368 over the whole city – so it seems likely I am undercounting taking the data from Google – but further investigation will be needed.