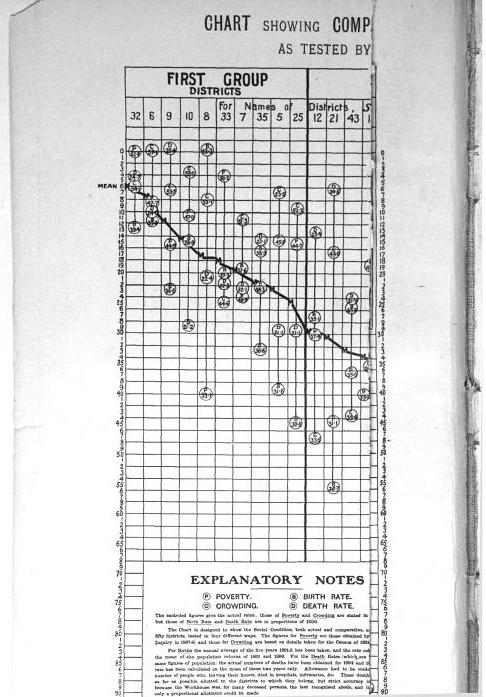

I was reading Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London (available entirely at Google books) and stumbled across this gem of a connected dot plot (between pages 18-19, maybe it came as a fold out in the book?)

(You will also get a surprise of the hand of the scanner in the page prior!) This reminded me I wanted to make a collection of my favorite historical examples of maps and graphs for criminology and criminal justice. If you read through Calvin Schmid’s Handbook of Graphical Presentation (available for free at the internet archive) it was a royal pain to create such statistical graphics by hand before computers. It makes you appreciate the effort all that much more, and many of the good ones will rival the quality of any graphic you can make on the computer.

Calvin Schmid himself has some of my favorite example maps. See for instance this gem from Urban Crime Areas: Part II (American Sociological Review, 1960):

The most obvious source of great historical maps in criminology though is from Shaw and McKay’s Juvenile Delinquency in Urban Areas. It was filled with incredible graphs and maps throughout. Here are just a few examples. (These shots are taken from the second edition in 1969, but they are all from the first part of the book, so were likely in the 1942 edition):

Dot maps

Aggregated to grid cells

The concentric zonal model

And they even have some binned scatterplots to ease in calculating linear regression equations

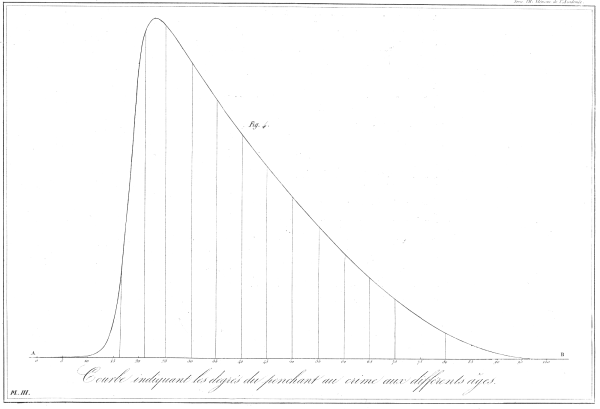

Going back further, Friendly in A.-M. Guerry’s moral statistics of France: Challenges for multivariable spatial analysis has some examples of Guerry’s maps and graphs. Besides choropleth maps, Guerry has one of the first examples of a ranked bumps chart (as later coined by Edward Tufte) of the relative rankings of the counts of crime at different ages (1833):

I don’t have access to any of Quetelet’s historical maps, but Cook and Wainer in A century and a half of moral statistics in the United Kingdom: Variations on Joseph Fletcher’s thematic maps have examples of Joseph Fletcher’s choropleth maps (as of 1849):

Going to more recent mapping examples, the Brantingham’s most notable I suspect is their crime pattern nodes and paths diagram, but my favorites are the ascii glyph contour maps in Crime seen through a cone of resolution (1976):

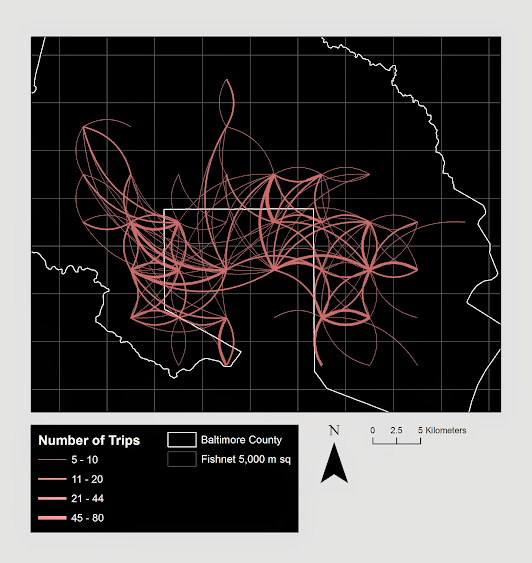

The earliest example of a journey-to-crime map I am aware of is Capone and Nichols Urban structure and criminal mobility (1976) (I wouldn’t be surprised though if there are earlier examples)

Besides maps, one other famous criminology graphic that came to mind was the age-crime curve. This is from Age and the Explanation of Crime (Hirschi and Gottfredson, 1983) (pdf here). This I presume was made with the computer – although I imagine it was still a pain in the butt to do it in 1983 compared to now! Andresen et al.’s reader Classics in Environmental Criminology in the Quetelet chapter has an age crime curve recreated in it (1842), but I will see if I can find an original scan of the image.

Edit: Was able to find an online scan of Quetelet’s original work in French. This has a fitted sine curve as one of the figures, but if you check out the tables he has binned arrest rates (page 65).

I will admit I have not read Wolfgang’s work, but I imagine he had graphs of the empirical cumulative distribution of crime offenses somewhere in Delinquency in a Birth Cohort. But William Spelman has many great examples of them for both people and places. Here is one superimposing the two from Criminal Careers of Public Places (1995):

Michael Maltz has spent much work on advocating for visual presentation as well. Here is an example from his chapter, Look Before You Analyze: Visualizing Data in Criminal Justice (pdf here) of a 2.5d kernel density estimate. Maltz discussed this in an earlier publication, Visualizing Homicide: A Research Note (1998), but the image from the book chapter is nicer.

Here is an album with all of the images in this post. I will continue to update this post and album with more maps and graphs from historical work in criminology as I find them. I have a few examples in mind — I plan on adding a multivariate scatterplot in Don Newman’s Defensible Space, and I think Sampson’s work in Great American City deserves to be mentioned as well, because he follows in much of the same tradition as Shaw and McKay and presents many simple maps and graphs to illustrate the patterns. I would also like to find the earliest network sociogram of crime relationships. Maltz’s book chapter has a few examples, and Papachristo’s historical work on Al Capone should be mentioned as well (I thought I remembered some nicer network graphs though in Papachristos’s book chapter in the Morselli reader).

Let me know if there are any that I am missing or that you think should be added to the list!