A question came up recently on cross validated about putting some numbers on the amount of bias in jury selection. I had a previous question of a similar nature, so it had been on my mind previously. The original poster did not say this was specifically for a Batson challenge, but that is simply my presumption. It is both amazing and maddening that given the same question four different potential analyses were suggested. Although it is a bit out of the norm for what I talk about, I figured it would be worth a post.

Some background on Batson

For some background, Batson challenges are specifically in the context of selecting jurors for a trial. (Everything that follows is specific to what I know about law in the US.) To select a jury first the court selects potential jurors for the venire from the general public. Then both the prosecution and defence counsels have the opportunity to question individuals in the venire. A typical flow seems to be that a panel of the venire is selected (say 10), then the court has a set of standardized questions they ask every individual potential juror. This part is referred to as voir dire. If the individual states they can not be impartial, or there is some other characteristic that indicates they cannot be impartial that potential juror can be eliminated for cause. Without intervention of counsel the standard questions by the court typically weeds out any obvious cases. After the standard questions both counsels have the opportunity to ask their own questions and further identify challenges for cause. There are no limits on who can be eliminated for cause.

The wrinkle specific to Batson though is that each counsel is given a fixed number of peremptory challenges. The number is dictated by the severity of the case (in more serious cases each side has a higher number of challenges). The wikipedia page says in some circumstances the defense gets more than the prosecution, but the total number is always fixed in advance.

The logic behind peremptory challenges is that either counsel can use personal discretion to eliminate potential jurors without needing a justification. Basically it is a fail-safe of the court to allow gut feelings of either counsel to eliminate jurors they believe will be partial to the opposing side. But based on the equal protection clause it was decided in Batson vs. Kentucky that one can not use the challenges solely based on race. As a side effect of allowing so many peremptory challenges, one can easily eliminate a particular minority group, as being a minority group they will only have a few representatives in the venire.

During the voir dire if the opposing counsel believes the opposition is using the peremptory challenges in a racially discriminatory manner, they can object with a Batson challenge. The supreme court decided on three steps to evaluate the challenge.

- The party that objected has the burden to prove a prima facie case that the challenges were used in a discriminatory manner. This includes an argument that the group is discriminated against is cognizable, and that there is additional numerical evidence of discrimination.

- Then the burden shifts on the party being challenged to justify the use of the peremptory challenges based on race neutral reasons.

- The burden then shifts back to the original challenging party. This is to dispute whether the reasons proferred for the use of the peremptory challenges are purely pretextual.

Witnessing the proceedings for this particular case in the New York court of appeals case is what prompted my interest, and I recommend reading their decision as a good general background on Batson challenges (the wikipedia page is lacking quite a bit). What follows is some number crunching specific to the first part, establishing a prima facie case of discrimination.

Now some numbers

Batson challenges are made in situ during voir dire. All the cases I am familiar with simply use fractions to establish that the peremptory challenges are being used in a discriminatory manner. The fact that the numbers are changing during voir dire makes the calculations of statistics more difficult. But I will address the ex post facto assessment of the first step given the final counts of the number of peremptory challenges and the total number on the venire with their racial distribution. This presumption I will later discuss how it might impact on the findings in a more realistic setting.

Consider the case of People vs. Hecker (linked to above). It happened that the peremptory challenges by the defence to exclude two Asian’s from the jury panel is what prompted the Batson challenge. Later on one other Asian juror was seated to the jury. The appeals court considered in this case whether step 1 was justified, so it is not a totally academic question to attempt to quantify the chances of two out of three Asian’s being challenged.

First, I will specify how we might put a number of this chance occurrence. If a person randomly selected 13 names out of a hat with 39 people, and of those names 3 individuals were Asian, what is the probability that 2 of those selected would be Asian? This probability is dictated by the hypergeometric distribution. More generally, the set up is:

- n equals the total number of eligible cases that are subject to be challenged

- p equals the total number of the race in question that are subject to be challenged

- k equals the total number of peremptory challenges used on the racial group in question

- d equals the total number of peremptory challenges

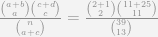

And the hypergeometric distribution is calculated using binomial coefficients as:

So plugging the numbers listed above into the formula, we get the probability of two out of three Asian jurors being challenged if the challenges were made randomly would be equal to below according to Wolfram Alpha:

So the probability of a chance occurrence given this particular set of circumstances is 22%, not terribly small, although may be sufficient given other circumstances to justify the first step (it seems the first step is intended that the burden is rather light). Where did my numbers come from though exactly? Given the circumstances of the case in the appeal decision the only number that would be uncontroversial would be p = 2, that two Asian jurors were excluded based on peremptory challenges. p = 3 comes from after the case, in which one other Asian juror was actually seated. It appears in the appeals case I linked to they consider the jury composition after the Batson challenge was initially brought, but obviously the initial trial judge can’t use that future information. I choose to use d = 13 because the defence only used 13 of their 15 peremptory challenges by the end of the seating. The total number n = 39 is the most difficult to come by.

The appeal case states that in the first pool 18 jurors were brought for questioning, 5 were eliminated for cause, and that both the defence and prosecution used 5 peremptory challenges. I chose to count the total number as 13 for this round, 18 minus the 5 eliminated for cause. In our pulling names out of the hat experiment though you may consider the number to be only 8, so not count the cases the prosecution used their peremptory challenges on. The second round brought another 18 potential jurors, of which 4 were eliminated for challenge. In this round the two Asian jurors were challenged by the defence when the judge asked to evaluate the first 9 of this panel (given the language it appears defence used 3 peremptory challenges during this evaluation of the first 9). At the end of the second round both parties used another 5 peremptory challenges. So to get the the total number of 39, I use 13 for the first round plus 14 for the second, although I could reasonably use 8 for the first and 9 for the second. I end up at 39 by using 13 + 14 + 12 – the last Asian juror (Kazuko) was the the 13th to be questioned on the third panel. One prior juror had been challenged for cause, so I count this as 12 towards the total of 39. There were a total of 26 panellists in this round, and the defence used a total of another 3 peremptory challenges, and there is no other information on whether the prosecution used any more peremptory challenges. (I’m unsure the total number of jurors seated for the case, so I can’t make many other guesses – the total number of jurors selected in the prior two rounds were 7). I don’t worry about the selection of the alternate juror for this analysis.

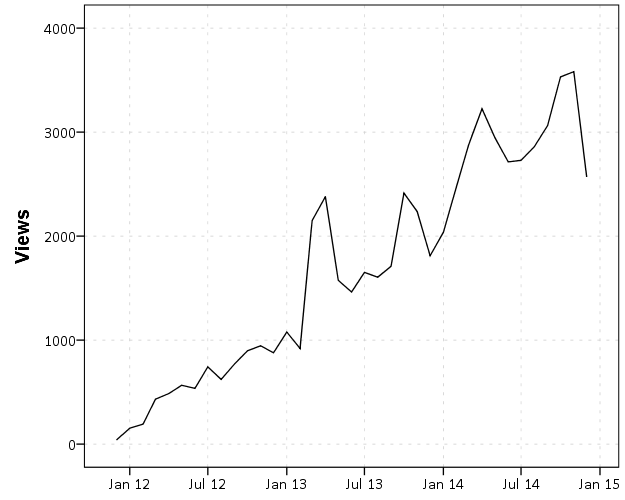

So lets try to apply this same analysis at the exact time the Batson challenge was raised, when the second Asian juror was eliminated. I prefer to make the calculations at the time the challenge was raised, as the opposing counsel may later alter their behavior in light of a prior Batson challenge. In doing this, now we have p = 2 and k = 2 (there was no other mention of any Asian’s being challenged for cause). We have a bit of uncertainty about d and n though. d at a minimum for the defence has to be 7 at this point (five in the first round plus the two Asians in the second round), but could be as many as 10 (5 in the first and 5 in the second). n could be as mentioned before 8 + 9 = 17 (excluding cases the prosecution challenged) or 13 + 14 = 27 (including all cases not challenged for cause). In the middle you may consider n to be 13 + 9 = 22, the exact point when the defence was asked to bring forth challenges for the first 9 seated on that round of the panel. So what difference does this make on the estimated probabilities? Well lets just graph the estimates for all values of d between 7 and 10, and n between 17 and 27. Here the lines are for different values of d (with labels at the beginning left part of the line), and the x axis is the different values of n. We can see the probabilities follow the pattern that as n increases and d decreases the probability of that combination goes down. Even over all these values the probability never goes below 5%. I do not know if a 5% probability is sufficient for the numerical justification of the prima facie case of discrimination. 22% seems too low a threshold to me (by chance about 1 in 5 times) but 5% may be good enough (by chance 1 in 20 times).

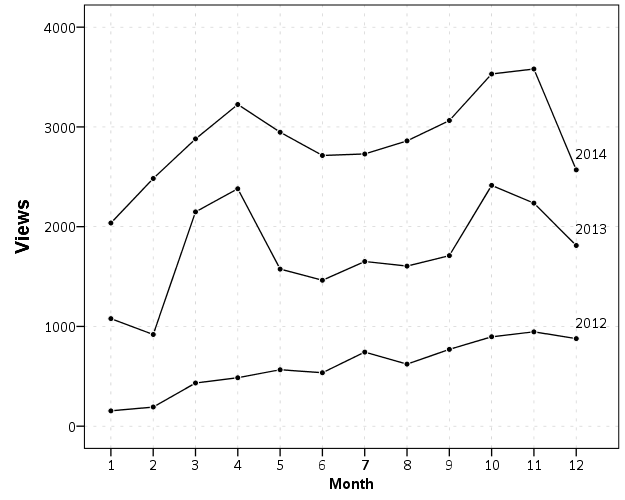

So lets try this same sensitivity analysis for the entire case. For the evaluation of everything after the fact I think p = 3 and k = 2 are largely uncontroversial, but lets vary d between 7 and 15 and n between 23 (chosen to be at the lower end of cases that were legitimately evaluated in the pool by the end I believe) to 45. Some of these situations are not commensurate with the limited information we have (e.g. d = 7 and n = 45 is not possible) but I think the graph will be informative anyway. My labelling could use more work, but the line on top is d = 15 and they increment until the line on bottom where d = 7.

So here we can see that the probability after the fact never gets much below 10%, and that is for lower values of d and higher values of n that are not likely possible given the data. So basically in the case that looks the worst for the defence here the probability of selecting two out of three Asian’s by random (giving varying numbers of peremptory challenges and varying the pool from which to draw them) is never below 10%. Not a terribly strong case that the numerical portion of step 1 has been satisfied. Basically, no matter what reasonable values you put in for d or n in this circumstance the probability of choosing 2 out of three Asian jurors randomly is not going to be much below 10%.

On some of the other suggested analyses

On the original question on CV I mentioned previously, besides my own suggested analysis here there were 3 other suggested analysis:

- Using a regression model to predict the probability of a racial group being challenged

- Analysis of Contingency tables

- Calculating all potential permutations, and then counting the percentage of those permutations that meet some criteria.

All three I do not think are completely unreasonable, but I prefer the approach I listed above. I will attempt to articulate those reasons.

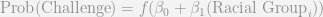

So first I will talk about the regression approach. This is generically a model of the form predicting the probability of a peremptory challenge based on the race of the potential juror:

The anonymous function is typically a logit (for a logistic model) or a probit function. This generalized linear model is then estimated via maximum likelihood, and one formulates hypothesis tests for the B_1 coefficient. The easy critique of this is that the test is not likely to be very powerful with the small samples – as the estimates are based on maximum likelihood and are only guaranteed to unbiased asymptotically. This could be a fairly simple exercise to attempt to see the behavior of this bias in the small samples, but I suspect it reduces the power of the test greatly. Also note that in the case where the subgroup of interest is always challenged, such as in the two out of two Asian’s in the Hecker case mentioned, the equation is not identified due to perfect separation. There are alternative ways to estimate the equation in the case of perfect separation, but this does not mitigate the small sample problem.

More generally, my original formulation of the data generating mechanism being the hypergeometric distribution, drawing names out of hat, is quite different than this. This is a model of the probability of anyone being peremptory challenged. One then estimates the model to see if the probability is increased among the racial group of interest. This is arguably not the question of interest. For instance, say the model estimated the probability of an Asian being challenged to be only 6%, and the probability of anyone else to be 4%. In one sense, this establishes the prima facie case of discrimination of Asian’s compared to everyone else, but does only a probability of 6% of using a peremptory challenge warrant a Batson challenge? I don’t think so. If you think that a challenge will never come with such low probabilities, you are right in that the expected probabilities for the racial group of question will not be that low when a Batson challenge is made, but once you consider the uncertainty in the estimates (e.g. 95% confidence intervals) they could easily be that low. On the flip side if the racial group is struck 96% of the time, but everyone else is struck 94% of the time, does that establish the numerical evidence of discrimination? I’m not sure, it may if this prevents any of the particular racial group being seated.

The analysis of contingency tables, in particular Fisher’s Exact Test, is exactly the same as my hypergeometric approach if one only considers the racial group of interest against all other parties. Fisher’s exact test is a reasonable approach over the more typical chi-square because, 1) the cells will be quite small, and 2) this is one of the unusual cases where the marginals are fixed. So making a 2 by 2 contingency table based on the very first example I gave (which resulted in a probability of around 22%) would be a table:

| Asian |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Other |

11 |

25 |

36 |

| Total |

13 |

26 |

39 |

For the formula the 2 by 2 table is referred to as:

| Asian |

a |

b |

a + b |

| Other |

c |

d |

c + d |

| Total |

a + c |

b + d |

n |

Which Fisher’s Exact Test can be formulated by the binomial coefficients:

Which if you look closely is exactly the same set of binomial coefficients for the hypergeometric test I listed previously. So, as long as one only tests the one racial group against all others Fisher’s Exact test of a 2 by 2 contingency table is exactly the same as my recommendation. I don’t particularly think the historical p-value <= 0.05 standard is necessary, but it is the same information.

What bothers me more about this approach is when people start adding other cells in the contingency table. In the first step you need to establish a pattern of discrimination against one particular cognizable group. The treatment of other groups is non sequitur to this question in the first step. (In People vs Black evaluations of how unemployment was treated for non-black jurors was considered is steps 2 and 3, but not in the first step.) Including other groups into the table though will change the outcome. Such ad hoc decisions on what racial groups to consider should not have any effect on the evidence of discrimination against the specific racial group of interest. This problem of what groups is similarly applicable to the regression approach mentioned above. Hypothesis tests of the coefficients will be dependent on what particular contrasts you wish to draw and will change the estimates if certain groups are specified in the equation.

The final approach, counting up particular permutations that meet a particular threshold is intuitive, but again has an ad hoc element, the same problem with choosing which racial groups will impact the test statistic. All of the approaches (including my own) need to be explicit about the groups being tested beforehand. Only monitoring one group as in the hypergeometric test I presented earlier is much simpler to justify ex post facto, but it still would be best to establish the cognizable groups before voir dire takes place. For the tests that use other racial or ethnic groups in the calculations are much more suspect to justification, as the picking and choosing of the other groups will impact the calculations.

Some recommendations

A typical question I get asked as an academic is, So what would you recommend to improve the situation? Totally reasonable question that I often don’t have a good answer to. It is easy to throw out recommendations without considering the entirety of the situation, and the complexities of the criminal justice system are no exception. With full awareness that no one with any authority will likely read my recommendations, my suggestions follow none-the-less.

The first is, only slightly in jest, is to only allow 1 peremptory challenge. There is no bright line rule on numerical evidence presented that is necessary to establish discrimination, but the NY State court of appeals case I mentioned did indicate that it takes more than 1 challenge to establish a pattern of discrimination. This may seem extreme, but the logic applies to the same to allowing fewer peremptory challenges. The fewer the challenges, the less capability either counsel has to entirely eliminate a particular racial group from the jury. It simultaneously makes counsels use of the challenges more precious, so they should be more hesitant to use them based on gut feelings predicated solely by racial stereotyping.

As another side effect (good or bad depending on how you look at it) it also makes the evaluation of whether one is using the challenges in a racially discriminatory manner much clearer. As I shown above, when d decreased the probability of the outcome generally decreased. For example with the Hecker case, pretend there were only a total of 5 peremptory challenges. So in this hypothetical situation have n = 20, d = 5, and p and k = 2 (if the number of n was much higher with the number of peremptory challenges limited to 5 for each side the jury would have to be close to set already by the time 20 individuals were questioned). The probability of this is 5%, whereas if d = 7 the probability is 11%. To be very generic, having fewer challenges makes particular racial patterns less likely by chance.

I understand the motivation for peremptory challenges, but it is unclear to me why such a large number are currently afforded for most cases. Also to the extent that timeliness is a priority for the court, allowing fewer challenges would certainly decrease the necessary time needed for voir dire. (Which was a concern in the Hecker case, as the court only allowed a very short time for questioning the panels.)

The second is that case-law should be established for cognizable groups, particularly given the racial make up of the defendent(s) and victim(s). Or, conversely, counsels should be required a priori to voir dire to establish the cognizable groups. This avoids cherry picking any group for a Batson challenge, as one could always specify a group based on the ex post facto characteristics of the groups used for peremptory challenges. To put a probability to whether a certain number of a particular group could be chosen at at random it is necessary to supply the hypothesis before looking at data. Ad hoc selections of a group could always occur, and with some of the other statistical tests ad hoc inclusion of cells in a contingency table or to include in a test statistic could impact the analysis. Making such a case a priori should prevent any nefarious manipulation of the numbers after the fact.

Neither of these appear to be too onerous to me to be reasonable suggestions. I doubt any lawyer or judge is going to be typing binomial coefficients into Wolfram Alpha during voir dire anytime soon though. Maybe I should make a look up table or nomogram for hypergeometric probabilities for typical values that would come up during voir dire. It would be pretty easy for a lawyer to keep a tally and then do a look up, or keep in mind before hand at what point a set of challenges is unlikely due to chance. With many peremptory challenges and few uses of a particular group, I suspect the probabilities of that happening by chance are much larger than people expect. The two out of two Asian’s in the Hecker case is a good example where the numerical evidence of discrimination is very weak no matter how you plug in the numbers.