Kieran Healy and James Moody recently posted a pre-print, Data visualization in sociology that is to appear in a forthcoming issue of the Annual Review of Sociology. I saw awhile ago on Kieran’s blog that he was planning on releasing a paper on data viz. in sociology and was looking forward to it. As I’m interested in data visualization as well, I’m glad to see the topic gain exposure in such a venue. After going through the paper I have several comments and critiques (all purely of my own opinion). Take it with a grain of salt, I’m neither a sociologist nor a tenured professor at Duke! (I will refer to the paper as HM from here on.)

Sociological Lags

The first section, Sociological Lags, is intended to set the stage for the contemporary use of graphics in sociology. I find both the historical review lacking in defining what is included, and the segway into contemporary use uncompelling. I break the comment in this section into three sections of my own making, the historical review, the current state of affairs & reasoning for the current state of affairs.

Historical Review of What Exactly?

It is difficult to define the scope when reviewing historical applications of visualization on sociology; both because sociology can be immensely broad (near anything to do with human behavior) and defining what counts as a visual graph is difficult. As such it ends up being a bit of a fools errand to go back to the first uses of graphics in sociology. Often Playfair is considered the first champion of graphing numeric summaries (although he has an obvious focus on macro-economics), but if one considers maps as graphics people have made those before we had words and numbers. Tufte often makes little distinction between any form of writing or diagram that communicates information, e.g. in-text sparklines, Hobbe’s visual table of contents to Leviathan on the frontpiece, or Galileo’s diagrams of the rings of Saturn. Paul Lewi in Speaking of Graphics describes the quipu as a visual tool used for accounting by the Incas. If one considers ISOTYPE counting picture diagrams as actual graphs, the Mayan hieroglphys for counting values would seemingly count (forgive my ingorance of anthropology, as I’m sure other examples that fit these seemingly simple criteria exist in other and older societies). Tufte gives an example of using mono-spaced type font, which in our base 10 counting system approximates a logarithmic chart if the numbers are right aligned in a column.

10000

1000

100

10

1

So here we come to a bit of a contradiction, in that one of the main premises of the article is to advocate the use of graphics over tables, but a table can be a statistical graphic under certain definitions. The word semi-graphic is sometimes used to describe these hybrid tables and graphics (Feinberg, 1979).

So this still leaves us the problem of defining the scope for a historical review. Ignoring the fuzzy definition of graphics laid out prior, we may consider the historical review to contain examples of visualizations from sociologists or applications of visualization to sociological inquiry in general. HM cite 6 examples at the top of page 4, which are a few examples of visualizations from sociologists (pictures please of the examples!) I would have liked to seen the work of Aldophe Quetelet mentioned as a popular historical figure in sociology, and his maps of reported crimes would be considered an example of earlier precedence for data visualization. (I distinctly remember a map at the end of Quetelet (1984) and it appears he used graphs in other works, so I suspect he has other examples I am not familiar with.)

Other popular historical figures that aren’t sociologists but analyzed sociological relevant data were geographers such as Booth’s poverty maps, Minard’s migration flows (Friendly, 2002a), and Guerry/Balbi & Fletcher’s maps of moral statistics (Cook & Wainer, 2012; Friendly, 2007). Other popular champions in public health are John Snow and Florence Nightingale (Brasseur, 2005). I would have liked HM to either had a broader review of historical visualization work pertinent to sociologists, or (IMO even better) more clearly defined the scope of the historical examples they talk about. Friendly (2008) is one of the more recent reviews that I know of talking about the historical examples, so I’d prefer just referring the reader there and then having a more pertinent review of applications within sociology. Although no bright line exists for who is a sociologist, this seems to me to be an easier way to limit the scope of a historical review. Perhaps restrict the discussion to its use in major journals or well known texts (especially methodology oriented ones). The lack of graphs in certain influential works is perhaps more telling than their inclusion. I don’t think Weber or Durkheim used any graphs or maps that I remember.

The Current State of Affairs

The historical discussion is pertinent as a build up to the current state of affairs, but the segway between examples in the early 1900’s and contemporary research is difficult. The fact that the work of Calvin Schmid isn’t mentioned anywhere in the paper is remarkable (or perhaps just indicative of his lack of influence – he still should be mentioned though!) Uses of mapping crime seems to be a strong counter-example of the lack of graphs in either olden or modern sociology; Shaw and McKay’s Juvenile Delinquency in Urban Areas has many exemplary maps and statistical graphics. Sampson’s Great American City follows suit with a great many scatterplots and maps. (Given my background I am prejudiced to be more familiar with applications in criminology.)

So currently in the article we go from a few examples of work in sociology around the turn of the 20th century to the lack of use of graphics in sociology compared to the hard sciences. This is well known, and Cleveland (1984) should have been cited in addition to the anecdotal examples of comparison to articles in Science. (And is noted later on that this in and of itself is a poor motivation for the use of more graphs.) What is potentially more interesting (and pertinent to sociologists) is the variation within sociology itself over time or between different journals in sociology. For instance; is more page space devoted to figures now that one does not need to draw your own graphs by hand compared to say in the 1980s? Do journals such as Sociological Methodology and Sociological Methods & Research have clearly more examples of using graphics compared to ASR or AJS? Has the use of graphics laggard behind the adoption of quantitative analysis in the field? Answering these questions IMO provides a better sense of the context of the contemporary use of graphs in sociology than simply repeating old hat comparing to other fields. It also provides a segway between the historical and contemporary use of graphics within sociology. Indeed it is "easy to find" examples of graphs in contemporary journal articles in sociology, and I would prefer to have some sort of quantitative estimate of the prevalence of graphics within sociological articles over time. This also allows investigation of the cultural impediment hypothesis in this section versus the technical impediment discussions later on. HM also present some hypotheses about the adoption of quantitative modelling in sociology in reference to other social science fields that would lend itself to empirical verification of this kind.

Reasoning For The Current State of Affairs

I find the sentences by HM peculiar:

But, somewhere along the line, sociology became a field where sophisticated statistical models were almost invariably represented by dense tables of variables along rows and model numbers along columns. Though they may signal scientific rigor, such tables can easily be substantively indecipherable to most readers, and perhaps even at times to authors. The reasons for this are beyond the scope of this review, although several possibly complementary hypotheses suggest themselves.

And can be interpreted in two different ways given the context. It can be interpreted as posing the question why are graphics preferable to tables, or why are graphics in relative disuse in sociology. For either I disagree it is outside the scope of the article!

If interpreted in the latter (why disuse of graphics in sociology) HM don’t follow their own advice, and give an excellent discussion of the warnings of graphics provided by Keynes. This section is my favorite in the paper, and I would have liked to see discussion on either training curricula in sociology or discussion of the role in graphs of popular sociological methodology text books. Again, I don’t believe Durkheim or Weber use graphs at all (although I provide other examples of prior scholars they have been exposed to did). Fisher has a chapter on graphs, so the concept isn’t foreign, and obviously the use of ANOVA and regression was adopted within sociology with open arms – why not graphical methods? Why is Schmid (1954) seemingly ignored? The discussion of Keynes is fascinating, but did Keynes really have that much influence on the behavior of sociologists? (I’m reminded of this great quote on the CV site on Wooldrige, 776 pages without a single graph!) This still doesn’t satisfactorily (to me) explain the current state of affairs. For instance a great counter example is Yule (1926); which was a pretty popular paper that used (22!) graphs to explain the behavior of time series. We are left to speculation about historical inertia of an economist as the reasoning for lack of discourse and use of graphics in contemporary sociological publications. I enjoyed the speculation, but I am unconvinced. Again having estimates of the proportion of page space devoted to graphs in sociology over time (and/or in comparison to the other social science fields mentioned) would lend credence to the hypotheses about cultural and technological impediments.

If you interpret the quoted sentence as posing the question why are graphics preferable to tables, then that seems to be crucial discussion to motivate the article to begin with, and I will argue is on topic in the authors next section, visualization in principle. HM miss a good opportunity to relate the quote of Keynes to when we want to use graphs (making relative comparisons) versus tables (which are best when we are just looking up one value, but we are not often interested in just looking up one value!)

Visualization in Principle

The latter sections of the paper, visualization in principle and practice, I find much more reasonable as reviews and well organized into sections (albeit the scope of the sections are still ill-defined). Most of my dissapointments from here on are ommissions that I feel are important to the discussion.

I was disappointed in this particular section of the article, as I believed it would have been a great opportunity to introduce concepts of graphical perception (e.g. Cleveland’s hierarchy), connect the piece to more contemporary work examining graphical perception, and even potentially provide more actionable advice about improving graphics for publication.

This section begins with a hod-podge list of popular viz. books. I was surprised to see Wilkinson’s Grammar of Graphics mentioned, and I was surprised to see Stephen Kosslyn’s books (which are more how to cook book like) and Calvin Schmid ommitted. IMO MacEachren’s How Maps Work should also be included on the shelf, but I’m not sure if that or any of those listed can be objectively defined as influential. Influential is a seemingly ill-defined criteria, and I would have liked to seen citation counts for any of these in sociology journals (I would bet they are all minimal). I presume this is possible as Neal Caren’s posts on scatterplot or Kieran’s philosophy citation network are examples using synonmous data. I find the list strange in that the books are very different in content (see Kosslyn (1985) for a review of several of them), and a reader may be misled in that they cover redundant material. The next part then discusses Tufte and his walkthrough of the famous March of Napoleon graphic by Minard and tries to give useful tidbits of advice along the way.

Use of Example Minard Graphic

While I don’t deny that the Minard example is a wonderful, classical example of a great graph, I would prefer to not perpetuate Tufte’s hyperbole as it beeing the best statistical graphic ever drawn. It is certainly an interesting application, but does time-stamped data of the the number of troops exemplify any type of data sociologists work with now? I doubt it. Part of why I’m excited by field specific interest in visualization is because in sociology (and criminology) we deal with data that isn’t satisfactorily discussed in many general treatments of visualization.

A much better example, in this context IMO, would have been Kieran Healy’s blog post on finding Paul Revere. It is as great an example as the Minard march, has direct relevance to sociologists, and doesn’t cover ground previously covered by other authors. It also is a great example of the use of graphical tools for direct analysis of sociological data. It isn’t a graph to present the results of the model, it is a graph to show us the structure of the network in ways that a model never could! Of course not everyone works with social network data either, but if the goal is to simply have a wow thats really cool example to promote the use of graphics, it would have sufficed and been more clearly on topic for sociology.

The use of an exemplar graphic can provide interest to the readers, but it isn’t clear from the onset of this section that this is the reasoning behind presenting the graphic. Napoleon’s March (nor any single graphic) can not be substantive enough fodder for description of guides to making better graphics. The discussion of topics like layering and small multiples are too superficial to constitute actionable advice (layering needs to be shown examples really to show what you are talking about).

If someone were asking me for the simple introduction to the topic, I would introduce Cleveland’s hierarchy JASA paper (Cleveland & McGill, 1984). For making prettier graphs, I would just suggest to The Visual Display of Quantitative Information and Stephen Few’s short papers. Cleveland’s hierarchy should really be mentioned somewhere in the paper.

This section ends with a mix of advice and more generic discussion on graphical methods, framing the discussion in terms of reproducible research.

Reproducible Research

While I totally endorse the encouragement of reproducible research, and I agree the technical programming skills for producing graphs are the same, I’m not sure I see as strong a connection to data visualization. In much of the paper the connections of direct pertinence to sociologists are not explicit, but HM miss a golden opportunity here to make one; data we often use is confidential in nature, providing problems of both sharing code and displaying graphics in publications. Were not graphing scatterplots of biological assays, but of peoples behavior and sensitive information.

IMO a list of criteria to improve the aesthetics of most graphs that are disseminated in social science articles are; print the graph as a high resolution PNG file or a vector file format (much software defaults to JPEG unfortunately), sensible color choices (how is ColorBrewer not mentioned in the article!) or sensible choices for line formats, and understanding how to make elements of interest come to the foreground in the plot (e.g. not too heavy of gridlines, use color selectively to highlight areas of interest – discussed under the guise of layering earlier in the Minard graphic section). This list of simple advice though for aesthetics can be accomplished in any modern statistical software (and has been possible for years now). The section ends up being a mix of advice about aesthetics of plots with advice about how to make complicated plots more understandable (e.g. talk about small multiples). Discussing these concepts is best kept seperated. Although good advice extends to both, a quick and dirty scatterplot doesn’t have the same expectations as a plot in a publication. (The model of clarity residual plots from R would not be so clear if they had 10,000 points although it still may be sufficient for most purposes.)

Visualization in Practice

This section is organized into exploratory data analysis and presenting the results of models. HM touch on pertinent examples to sociologists (mainly large datasets with high variance to signals that are too complicated for bivariate scatterplots to tell the whole story). I enjoyed this section, but will mention additional examples and discussion that IMO should have been included.

EDA

HM make the great point that EDA and confirmatory analysis are never seperate, and that we can use thoughts from EDA to evaluate regression models. This IMO isn’t anything different than what Tukey talks about when he takes out row and column effects, it is just the scale of the number of data points and ability to fit models is far beyond any examples in Tukey’s EDA.

For the EDA section on categorical variables notable omissions are mosaic plots (Friendly, 1994) – which are mentioned but not shown in the pairs plot example and later on page 23 – and techniques for assessing residuals in logistic regression models (Greenhill et al., 2011; Esarey & Pierce, 2012). When discussing parallel coordinate plots mention should also be made of extensions to categorical data (Bendix et al. 2005; Dang et al. 2010; Hofmann & Vendettuoli, 2013). Later on mention is made that mosaic plots one needs to develop gestalt to interpret them (which I guess we are born with the ability to interpret bar graphs and scatterplots?) The same is oft mentioned for interpreting parallel coordinate plots, and anything that is novel will take some training to be able to interpret.

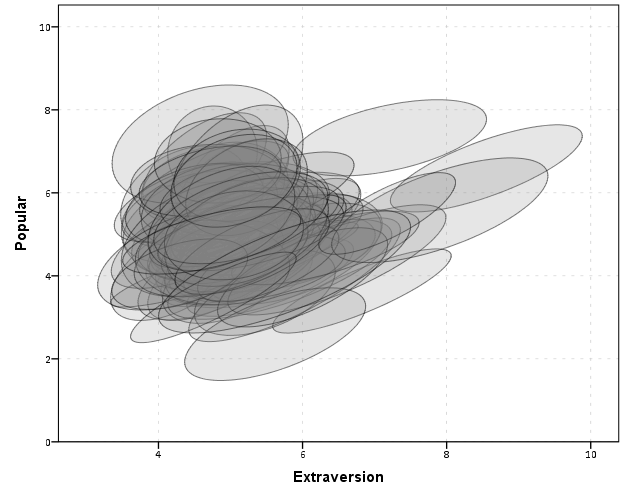

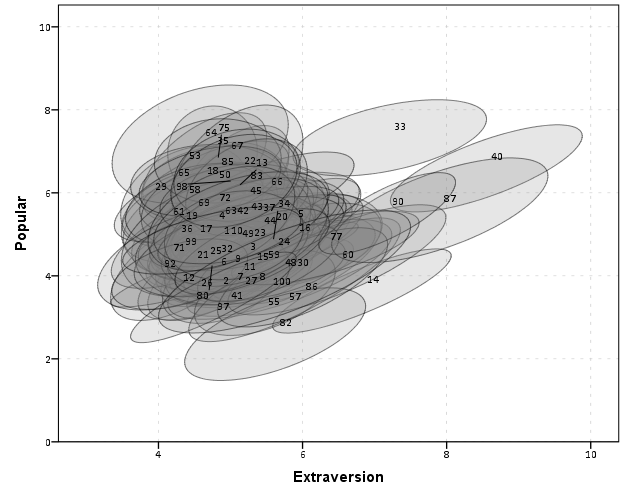

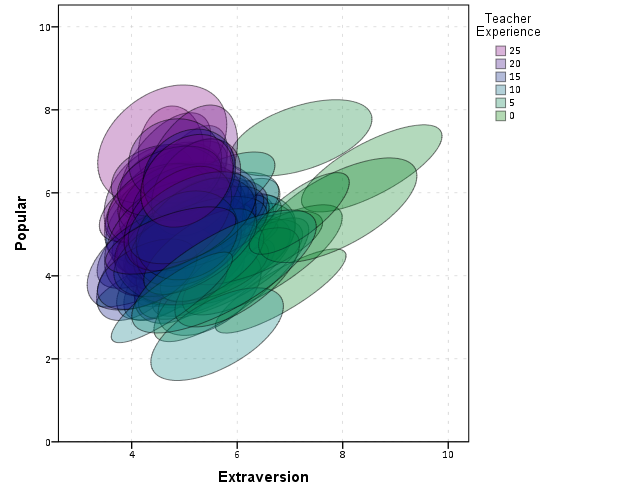

For continous models partial residual plots should be mentioned (Fox, 1991), and ellipses and caterpillar plots should be mentioned in relation to multi-level modelling (Afshartous & Wolf, 2007; Friendly et al. 2013; Loy & Hofmann 2013) as well as corrgrams for simple data reduction in SPLOMS (Friendly, 2002b). From the generic discussion of Bourdieu it sounds like they are discussing bi-plots or some sort of similar data reduction technique.

I should note that this is just my list of things I think deserve mention for application to sociologists, and the task of what to include is essentially an impossible one. Of course what to include is arbitrary, but I base it mainly on tasks I believe are more common for quantitative sociologists. This is mainly regression analysis and evaluating causal relationships between variables. So although parallel coordinate plots are a great visualization tool for anyone to be familiar with, I doubt it will be as interesting as tools to evaluate the fit or failure of regression models. HM mention that PCP plots are good for identifying clusters and outliers (they aren’t so good for evaluating correlations). Another example (that HM don’t mention) would be treemaps. It is an interesting tool to visualize hierarchical data, but I agree that it shouldn’t be included in this paper as such hierarchical data in sociology is rare (or at least many applications of interest aren’t immediately obvious to me). The Buja et al. paper on using graphs for inference is really neat idea, (and I’m glad to see it mentioned) but I’m more on the fence as to whether it should have taken precedence to some of the other visualizations ideas I mention.

EDA for examining the original data and for examining model residuals are perhaps different enough that it should have its own specific section (although HM did have a nice discussion of this distinction). Examining model residuals is always preached but is seemingly rarely performed. More examples for the parade of horribles I would enjoy (Figure 1 presents a great one – maybe find one for a more complicated model would be good – I know of a few using UCR county data in criminology but none off-hand in sociology). The quote from Gelman (2004) is strange. Gelman’s suggestions for posterior simulations to check the model fit can be done with frequentist models, see King et al. (2000) for basically the same advice (although the citation is at an appropriate place). Also King promotes these as effective displays to understand models, so they are not just EDA then but reasonable tools to summarize models in publications (similar to effect plots later shown).

Presenting model results

The first two examples in this section (Figure 7 histogram and Figure 8 which I’m not sure what it is displaying) seem to me that they should be in the EDA section (or are not cleary defined as presenting results versus EDA graphics). Turning tables into graphs (Cook & Teo, 2011; Gelman et al. 2002; Feinberg & Wainer, 2011; Friendly & Kwan, 2011; Kastellec & Leoni, 2007) is a large omission in this section. Since HM think that tables are used sufficiently, this would have been a great opportunity to show how some tables in an article are better presented as graphs and make more explicit how graphs are better at displaying regression results in some circumstances (Soyer & Hogarth, 2012). It also would have presented an opportunity to make the connection that data visualization can even help guide how to make tables (see my blog post Some notes on making effective tables and Feinberg & Wainer (2011)).

Examples of effects graphs are great. I would have liked mentions of standardizing coefficients to be on similar or more interpretable scales (Gelman & Pardoe, 2007; Gelman, 2008) and effectively displaying uncertainty in the estimates (see my blog post and citations Viz. weighted regression in SPSS and some discussion).

Handcock & Morris (1999) author names are listed in the obverse order in the bibliography in case anyone is looking for it like I was!

In Summary and Moving Forward

As oppossed to ending with a critique of the discussion, I will simply use this as a platform to discuss things I feel are important for moving forward the field of data visualization within sociology (and more broadly the social sciences). First, things I would like to see in the social sciences moving forward are;

- More emphasis on the technical programming skills necessary to make quality graphs.

- Encourage journals to use appropriate graphical methods to convey results.

- Application of the study of data viz. methods as a study worthy in sociology unto itself.

The first suggestion, emphasis on technical programming skills, is in line with the push towards reproducible research. I would hope programs are teaching the statistical computing skills necessary to be an applied quantitative sociologist, and teaching graphical methods should be part and parcel. The second suggestion, encourage journals to use appropriate graphical methods, I doubt is objectionable to most contemporary journals. But I doubt reviewers regularly request graphs instead of tables even where appropriate. It is both necessary for people to submit graphs in their articles and for reviewers to suggest graphs (and journals to implement and enforce guidelines) to increase usage in the field.

When use of graphs becomes more regular and widespread in journal articles, I presume the actual discussion and novel applications will become more regular within sociological journals as well. James Moody is a notable exception with some of his work on networks, and I hope more sociologists are motivated to develop tools unique to their situation and test the efficacy of particular displays. Sociologists have some unique circumstances (spatial and network data, mostly categorical dimensions, low signal/high variance) that call for not just transporting ideas from other fields, but attention and development within sociology itself.

Citations

- Afshartous, D. and Wolf, M. (2007). Avoiding ‘data snooping’ in multilevel and mixed effects models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 170(4):1035-1059.

- Bendix, F., Kosara, R., and Hauser, H. (2005). Parallel sets: visual analysis of categorical data. In IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization, 2005. INFOVIS 2005., pages 133-140. IEEE.

- Brasseur, L. (2005). Florence nightingale’s visual rhetoric in the rose diagrams. Technical Communication Quarterly, 14(2):161-182.

- Cleveland, W. S. and McGill, R. (1984). Graphical perception: Theory, experimentation, and application to the development of graphical methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(387):531-554.

- Cleveland, W. S. (1984). Graphs in scientific publications. The American Statistician, 38(4):261-269.

- Cook, Alex R. & Shanice W. Teo. (2011) The communicability of graphical alternatives to tabular displays of statistical simulation studies. PLoS ONE 6(11): e27974.

- Cook, R. and Wainer, H. (2012). A century and a half of moral statistics in the united kingdom: Variations on joseph fletcher’s thematic maps. Significance, 9(3):31-36.

- Dang, T. N., Wilkinson, L., and Anand, A. (2010). Stacking graphic elements to avoid Over-Plotting. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 16(6):1044-1052.

- Esarey, Justin & Andrew Pierce. 2012. Assessing fit quality and testing for misspecification in binary-dependent variable models. Political Analysis 20(4): 480-500. Preprint PDF Here

- Feinberg, R. A. and Wainer, H. (2011). Extracting sunbeams from cucumbers. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 20(4):793-810.

- Fienberg, S. E. (1979). Graphical methods in statistics. The American Statistician, 33(4):165-178.

- Fox, J. (1991). Regression diagnostics. Number no. 79 in Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage.

- Friendly, M. (1994). Mosaic displays for Multi-Way contingency tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89(425):190-200.

- Friendly, M. (2002a). Visions and Re-Visions of charles joseph minard. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 27(1):31-51.

- Friendly, M. (2002b). Corrgrams: Exploratory displays for correlation matrices. The American Statistician, 56(4):316-324.

- Friendly, M. (2007). A.-M. guerry’s moral statistics of france: Challenges for multivariable spatial analysis. Statistical Science, 22(3):368-399.

- Friendly, M. (2008). The golden age of statistical graphics. Statistical Science, 23(4):502-535.

- Friendly, M., Monette, G., and Fox, J. (2013). Elliptical insights: Understanding statistical methods through elliptical geometry. Statistical Science, 28(1):1-39.

- Friendly, Michael & Ernest Kwan. 2011. Comment on Why tables are really much better than graphs. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 20(1): 18-27.

- Gelman, A. (2008). Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Statistics in medicine, 27(15):2865-2873.

- Gelman, A. and Pardoe, I. (2007). Average predictive comparisons for models with nonlinearity, interactions, and variance components. Sociological Methodology, 37(1):23-51.

- Gelman, Andrew, Cristian Pasarica & Rahul Dodhia (2002). Let’s practice what we preach. The American Statistician 56(2):121-130.

- Greenhill, Brian, Michael D. Ward & Audrey Sacks. 2011. The separation plot: A new visual method for evaluating the fit of binary models. American Journal of Political Science 55(4):991-1002.

- Hofmann, H. and Vendettuoli, M. (2013). Common angle plots as Perception-True visualizations of categorical associations. Visualization and Computer Graphics, IEEE Transactions on, 19(12):2297-2305.

- Kastellec, Jonathan P. & Eduardo Leoni. (2007). Using graphs instead of tables in political science. Perspectives on Politics 5(4):755-771.

- King, G., Tomz, M., and Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2):347-361.

- Kosslyn, S. M. (1985). Graphics and human information processing: A review of five books. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 80(391):499-512.

- Kosslyn, S. M. (1994). Elements of graph design. WH Freeman New York.

- Lewi, P. J. (2006). Speaking of graphics. http://www.datascope.be/sog.htm

- Loy, A. and Hofmann, H. (2013). Diagnostic tools for hierarchical linear models. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 5(1):48-61.

- MacEachren, A. M. (2004). How maps work: representation, visualization, and design. Guilford Press.

- Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press.

- Schmid, C. F. (1954). Handbook of graphic presentation. Ronald Press Company. http://archive.org/details/HandbookOfGraphicPresentation

- Shaw, C. R. and McKay, H. D. (1972). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas: a study of rates of delinquency in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. A Phoenix Book. University of Chicago Press.

- Soyer, E. and Hogarth, R. M. (2012). The illusion of predictability: How regression statistics mislead experts. International Journal of Forecasting, 28(3):695-711.

- Tufte, E. R. (1983). The visual display of quantitative information. Graphics Press.

- Quetelet, A. (1984). Adolphe Quetelet’s Research on the propensity for crime at different ages. Criminal justice studies. Anderson Pub. Co.

- Yule, G. U. (1926). Why do we sometimes get Nonsense-Correlations between Time-Series?-a study in sampling and the nature of Time-Series. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 89(1):1-63.