The other day I had a conversation with a colleague about calculating travel time distances and comparing them to actual geographic distances (aka as the crow flies). Being unfamiliar with the Network add-on in ArcGIS I figured I would take a stab at this task with the Google Distance API. Being lazy, I’m not going to explain the code, but in a nutshell works basically the same way as my prior code samples for the Google places API. The main difference is that this code will only return one result per record in the original file.

BEGIN PROGRAM Python.

import urllib, json

#This parses the returned json to pull out the distance in meters and

#duration in seconds, [None,None] is returned is status is not OK

def ExtJsonDist(place):

if place['rows'][0]['elements'][0]['status'] == 'OK':

meters = place['rows'][0]['elements'][0]['distance']['value']

seconds = place['rows'][0]['elements'][0]['duration']['value']

else:

meters,seconds = None,None

return [meters,seconds]

#Takes a set of lon-lat coordinates for origin and destination,

#plus your API key and returns the json from the distance API

def GoogDist(OriginX,OriginY,DestinationX,DestinationY,key):

MyUrl = ('https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/distancematrix/json'

'?origins=%s,%s'

'&destinations=%s,%s'

'&key=%s') % (OriginY,OriginX,DestinationY,DestinationX,key)

response = urllib.urlopen(MyUrl)

jsonRaw = response.read()

jsonData = json.loads(jsonRaw)

data = ExtJsonDist(jsonData)

return data

END PROGRAM.

So because for each pair of origin and destinations this only returns one result, we can use this function in SPSSINC TRANS to return the distance in meters and the travel time in seconds without having to worry about any other data manipulations in python. The only additional item we need besides the origin and destination latitude and longitude are your Google API key in a seperate string variable. So if you had the OD coordinates in the fields Ox,Oy,Dx,Dy for origin longitude, origin latitude etc. the code would simply be:

STRING MyKey (A100).

COMPUTE MyKey = '!!!!!!!YOUR KEY HERE!!!!!!!!!!!!!'.

EXECUTE.

SPSSINC TRANS RESULT=Meters Seconds TYPE=0 0

/FORMULA GoogDist(OriginX=Ox,OriginY=Oy,DestinationX=Dx,DestinationY=Dy,key=MyKey).

Note the Google distance API has a limit of 2,500 queries per day, and unlike the places API can not be upped by providing verification (unfortunately).

The context the colleague was asking was for a project about prison visitation, for some background see a report by Jacquelyn Greene at the New York State DCJS, and I saw recently Joshua Cochran plus a few other of the Florida State folks published a paper about prisoner visitation in Florida. So I figured a good test would be calculating the correlation between travel distance and geographic distances between all of the zip codes in New York State to one particular prison.

I chose to calculate the distances between the centroid of zip code areas and Attica State prison, which is in between Rochester and Buffalo in the westernmost part of New York state. FYI zip code areas are not well defined, so don’t ask me how exactly the ones I used here are calculated, but I got them from the New York State GIS clearinghouse, and they were from 2009.

So as long as you have the prior python function GoogDist defined, here is a set of brief syntax to grab the zip code data and calculate the travel time and travel distance. This does take a few minutes, but I never had a problem with the 100 queries per 1 minute suggestion by Google in my tests. Their are 2,332 zip code areas in New York State, so beware this about uses up your limit for the day (and you have no second chances)! This took me about 8 minutes to calculate.

*Grab the online data.

SPSSINC GETURI DATA

URI="https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/3385251/NewYork_ZipCentroids.sav"

FILETYPE=SAV DATASET=NY_Zips.

*Travel distance to Attica.

COMPUTE Dx = -78.276205.

COMPUTE Dy = 42.850721.

STRING MyKey (A100).

COMPUTE MyKey = '!!!!!!!YOUR KEY HERE!!!!!!!!!!!!!'.

EXECUTE.

SPSSINC TRANS RESULT=Meters Seconds TYPE=0 0

/FORMULA GoogDist(OriginX=LongCent,OriginY=LatCent,DestinationX=Dx,DestinationY=Dy,key=MyKey).

We can also calculate the euclidean "crows flies" distance via the extendedTransforms python code. This returns the distance miles, and so the following code converts the two distances to kilometers and the time to minutes.

*As the crow flies distance.

SPSSINC TRANS RESULT=MilesCrow TYPE=0

/FORMULA extendedTransforms.ellipseDist(lat1=LatCent,lon1=LongCent,lat2=Dy,lon2=Dx,inradians=False).

*Convert to meters.

COMPUTE KMCrow = (MilesCrow*1609.34)/1000.

COMPUTE KMTrav = Meters/1000.

COMPUTE Minutes = Seconds/60.

FORMATS KMCrow KMTrav Minutes (F6.0).

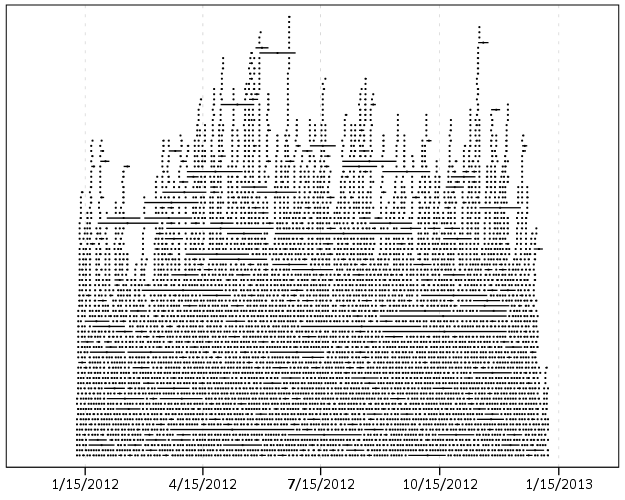

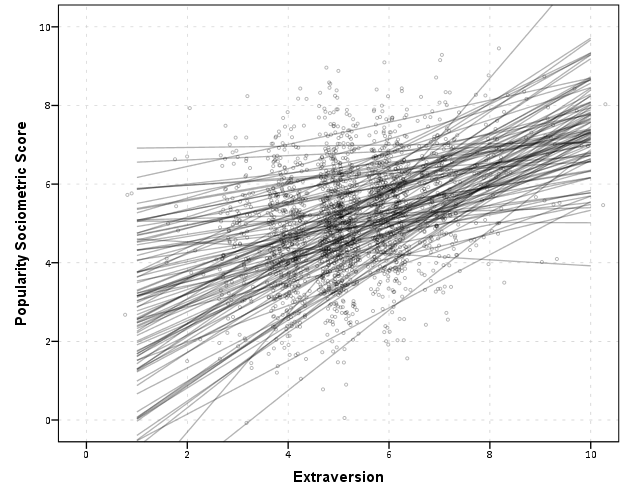

Now, part of my suggestion was actually that calculating travel times is not necessary, because they will be highly correlated with each other. Here is the scatterplot matrix of the three measures, travel distance, geographic distance, and travel time. The inter-item correlations are all around .99.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=KMCrow KMTrav Minutes

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: KMCrow=col(source(s), name("KMCrow"))

DATA: KMTrav=col(source(s), name("KMTrav"))

DATA: Minutes=col(source(s), name("Minutes"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1.1), ticks(null()))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2.1), ticks(null()))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), gap(0px))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), gap(0px))

TRANS: KMCrow_label = eval("KMCrow")

TRANS: KMTrav_label = eval("KMTrav")

TRANS: Minutes_label = eval("Minutes")

ELEMENT: point(position((KMCrow/KMCrow_label+KMTrav/KMTrav_label+Minutes/Minutes_label)*

(KMCrow/KMCrow_label+KMTrav/KMTrav_label+Minutes/Minutes_label)),

size(size."2"), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.8"))

END GPL.

CORRELATIONS VARIABLES= KMCrow KMTrav Minutes.

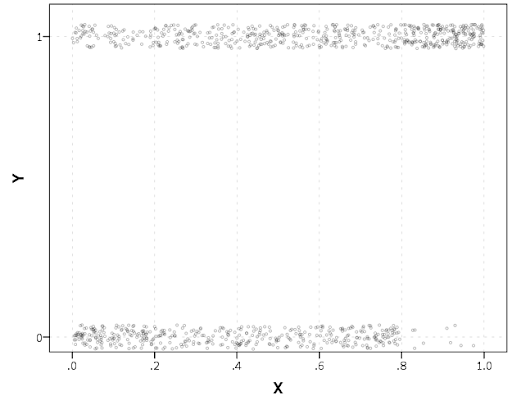

I expected that the error would get larger for larger travel and geographic distances, so to investigate this a simple graphical check is to estimate the difference between the two measures on the Y axis and the mean of the two measures on the X axis. Depending on who you ask, this is a Tukey mean difference plot or a Bland-Altman plot. Generally when comparing the scatterplot matrices it is easier to see the spread when you detilt the plot (using Tukey’s terminology), and calculating the differences is one way to do the detilting.

Here I calculate Dif = TravelDistance - GeoDistance, as I know the travel distance will always be larger than the geographic distance. For simplicity I just plot the geographic distance on the x axis instead of the mean of the two measures.

*Tukey mean difference chart.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=KMTrav KMCrow MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: KMTrav=col(source(s), name("KMTrav"))

DATA: KMCrow=col(source(s), name("KMCrow"))

TRANS: Dif = eval(KMTrav - KMCrow)

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Travel - Crows"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Crows Distance (in Kilometers)"))

ELEMENT: point(position(KMCrow*Dif))

END GPL.

This shows three particular things:

- It appears to be a mostly mixture of two separate linear regressions

- Within each mixture the measurement error is close to a constant multiple of the geographic distance

- There are some outliers as fingers of large travel distances extending from the point cloud.

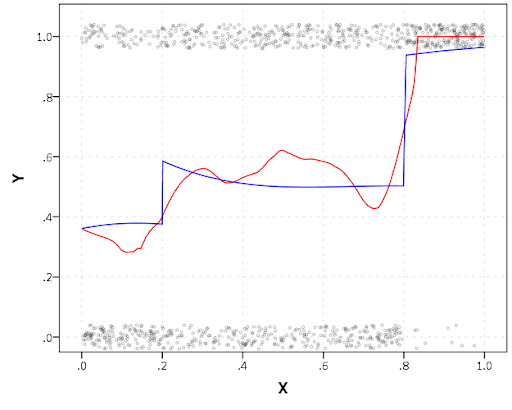

Some more EDA shows that the mixture is reflective of being close to Interstate 90 – those cities (like Albany and Syracuse) nearby the highway have a shorter travel time. Here what I did was estimate the linear regression for the prior plot and then color the residuals. Then I made a side-by-side set of the latitude-longitude coordinates next to the same scatterplot (colored). I can’t tell from this plot, but some of the high outliers appears in a cluster in downstate, maybe in the Catskills. But there are a few other of the high outliers shown around the state.

*Note this is the same as estimating regression on differences.

*see http://stats.stackexchange.com/a/15759/1036.

REGRESSION

/MISSING LISTWISE

/STATISTICS COEFF OUTS R ANOVA

/CRITERIA=PIN(.05) POUT(.10)

/NOORIGIN

/DEPENDENT KMTrav

/METHOD=ENTER KMCrow

/SAVE RESID(Resid1).

*Hmm, we have a mixture, lets see what explains that.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=LongCent LatCent Resid1 KMTrav KMCrow

MISSING=LISTWISE REPORTMISSING=NO

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

PAGE: begin(scale(500px,800px))

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: LongCent=col(source(s), name("LongCent"))

DATA: LatCent=col(source(s), name("LatCent"))

DATA: Resid1=col(source(s), name("Resid1"))

DATA: KMTrav=col(source(s), name("KMTrav"))

DATA: KMCrow=col(source(s), name("KMCrow"))

TRANS: Dif = eval(KMTrav - KMCrow)

GRAPH: begin(origin(15%, 5%), scale(81%, 40%))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), null())

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), null())

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), null())

SCALE: linear(aesthetic(aesthetic.color), aestheticMinimum(color.lightgrey), aestheticMaximum(color.black))

ELEMENT: point(position(LongCent*LatCent), color.interior(Resid1), size(size."5"), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.7"))

GRAPH: end()

GRAPH: begin(origin(15%, 50%), scale(81%, 40%))

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Travel - Crows"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Crows Distance (in Kilometers)"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), null())

SCALE: linear(aesthetic(aesthetic.color), aestheticMinimum(color.lightgrey), aestheticMaximum(color.black))

ELEMENT: point(position(KMCrow*Dif), color.interior(Resid1), size(size."5"), transparency.exterior(transparency."0.7"))

GRAPH: end()

PAGE: end()

END GPL.

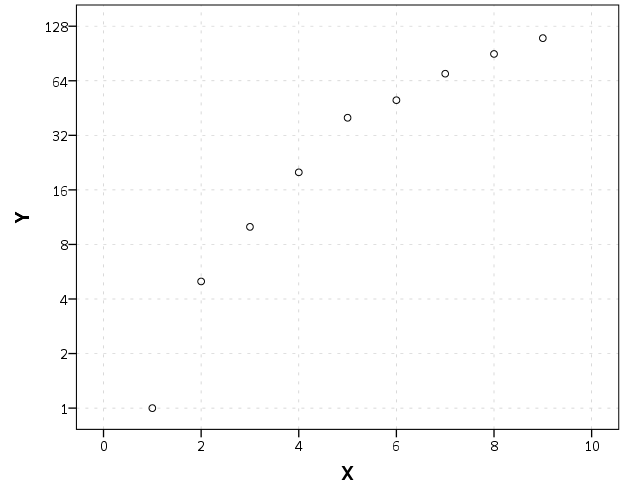

The linear regression gives a rough estimate for the relationship between travel distance and geographic distance in this sample that is about:

Travel Distance in = -4.7 + 1.3*Geographic Distance

A better model would include an interaction between distance to I-90 (and then maybe a term for being in the mountains), but again I am lazy! Obviously the negative intercept doesn’t make physical sense, so you really only want to use this for geographic distances of say 50 kilometers or larger, else it will likely be an underestimate. The opposite is true if you are close to I-90, this formula is likely to be an overestimate.

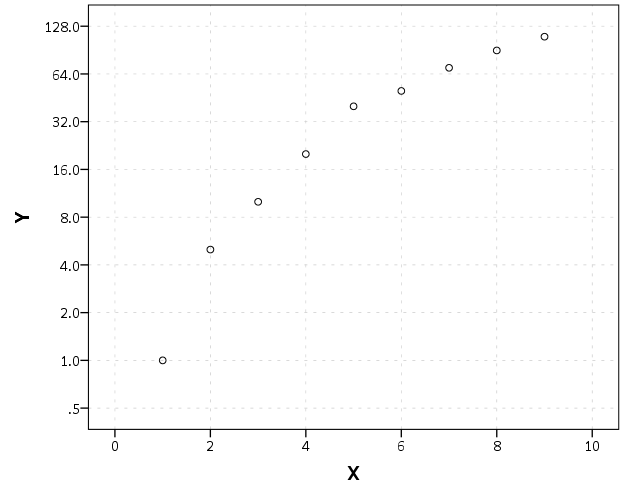

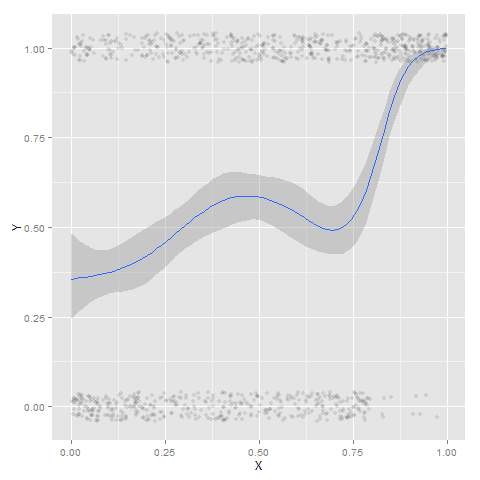

The same exercise for the travel time in minutes gives the equation Travel Time in Minutes = 9 + 0.75*(Geographic Distance in Kilometers):

*Minutes as a function of distance.

REGRESSION

/MISSING LISTWISE

/STATISTICS COEFF OUTS R ANOVA

/CRITERIA=PIN(.05) POUT(.10)

/NOORIGIN

/DEPENDENT Minutes

/METHOD=ENTER KMCrow

/SAVE RESID(MinResid).

COMPUTE AbsResid = ABS(MinResid).

COMPUTE DirResid = MinResid/AbsResid.

GGRAPH

/GRAPHDATASET NAME="graphdataset" VARIABLES=Minutes KMCrow AbsResid DirResid

/GRAPHSPEC SOURCE=INLINE.

BEGIN GPL

SOURCE: s=userSource(id("graphdataset"))

DATA: Minutes=col(source(s), name("Minutes"))

DATA: KMCrow=col(source(s), name("KMCrow"))

DATA: AbsResid=col(source(s), name("AbsResid"))

DATA: DirResid=col(source(s), name("DirResid"), unit.category())

TRANS: Dif = eval(KMTrav - KMCrow)

GUIDE: axis(dim(2), label("Travel Minutes"))

GUIDE: axis(dim(1), label("Crows Distance (in Kilometers)"))

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.color.interior), null())

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.transparency.interior), null())

GUIDE: legend(aesthetic(aesthetic.size), null())

SCALE: linear(aesthetic(aesthetic.size), aestheticMinimum(size."3"), aestheticMaximum(size."13"))

SCALE: linear(aesthetic(aesthetic.transparency), aestheticMinimum(transparency."0.3"), aestheticMaximum(transparency."0.9"), reverse())

ELEMENT: point(position(KMCrow*Minutes), color.interior(DirResid), transparency.interior(AbsResid),

size(AbsResid), transparency.exterior(transparency."1"))

ELEMENT: line(position(smooth.linear(KMCrow*Minutes)))

END GPL.

Again the mixture appears, but the linear regression appears as a much closer fit between geographic distance and travel time.

So in both cases, at least in this sample, it appears it is not really necessary to calculate travel distance. One can make a pretty good guess as to the travel distance simply given the geographic distance. Or going the other way using Pennsylvania speak, if I say the distance between two locations is about 1 hour this would translate into about 68 kilometers (i.e. 42 miles).